“Are you wearing trousers?” The words were out before she could rein them in.

His good eye met hers with a piercing brown gaze. “No.”

She’d never in her life been so embarrassed as in the wake of that single, simple word. She wished to crawl beneath the table. She might have done, if doing so wouldn’t have brought her entirely too close to the source of her embarrassment.

Thank heavens, he changed the topic. “You did not answer me.”

She couldn’t remember the question. She couldn’t remember any question in the entirety of her life but her last. She was mortified.

“How do you know I’ve come to town before now?” he repeated.

“I read the papers, just as you do,” she said. “You’re a particular favorite when you arrive in town.”

“Oh?” he said, as though he did not know it already.

“Oh, yes,” she said, recalling the way the scandal sheets described him, the ladies’ dark dream. She supposed he was a particular specimen, if one liked the tall, broad, and brutish sort of thing. Lily did not like it. Not at all. “The whole of London is warned to put out the sturdy furniture, in the event you happen along for tea.”

A muscle in his cheek tightened slightly, and Lily was surprised that the triumph she expected to feel knowing that she’d struck true did not come. Instead, she felt slightly guilty.

She should apologize, she knew, but instead bit her tongue in the long, uncomfortable moment that followed, during which he remained still as stone, coolly regarding her. They might have stood there for an age, in a battle of will, if not for the long strand of drool that dropped from one dog’s jowl to the carpet below.

Lily looked to the spot before saying, “That carpet cost three hundred pounds.”

“What did you say?”

She smirked at his shock. “And now it has been christened with your beast’s saliva.”

“Why in hell did you spend three hundred pounds on a carpet? For people to walk on?”

“You gave me leave to decorate the house as I saw fit.”

“I did no such thing.”

“Ah, of course,” she replied. “Your solicitor did. And, if I am to live in such a cage, my lord, it may as well be gilded, don’t you think?”

“We return to the bird metaphor?”

“Clipped wings and all,” she said.

He lifted his paper once more, his reply dry as sand. “It seems to me that your wings work very well, little wren.”

She stilled, not liking the unsettling knowledge in the words. Returned to the original topic. “You took no interest in the house, Your Grace, so I see no need for you to live in it.”

He replied from behind his newspaper. “I find I have an interest in it now.”

The cool statement reminded her of why she had entered the breakfast room to begin with. She took a deep breath. “You are not—”

“Staying. Yes. I am not without ability to hear.”

She didn’t doubt his sense of hearing. She doubted his sense, full stop. But it did not matter. The house was large enough for her to avoid him until her funds arrived, and she was free of him. And London.

Before she could say as much, however, they were interrupted by the arrival of the butler, Hudgins. “Your Grace,” the ancient man croaked as he doddered into the room leaning heavily on a cane, a slim parcel under his arm. “A missive has arrived for you.”

Lily turned to assist the butler—always half doubting his ability to get from one location to the next without hurting himself—removing the parcel from his hands. “Hudgins, you mustn’t overtax yourself.”

The butler looked to her, clearly insulted, and snatched the parcel back. “Miss Hargrove, I am one of London’s best butlers. I can certainly carry a parcel to the master of the house.”

The haughty words sent heat rushing through her—embarrassment of her own. His quick retort did not simply reveal that he’d been insulted, but also served to remind her of her place, neither above nor belowstairs. And certainly not permitted to instruct the staff in front of the duke.

She immediately searched for a way to make amends as he doddered toward the duke, setting the envelope on the table.

“Thank you, Hudgins,” Alec said quietly, the low burr rumbling across the room. “Before you leave, there is another matter with which you might assist me.”

Lily was forgotten. The butler straightened as much as his aging bones would allow, obviously eager to prove he was more than able to help. “Of course, Your Grace. Whatever you require. The entire staff is here for your aid.”

“As this is a matter of serious import, I would not wish for any but you to aid me.”

Lily turned to the duke with a frown—wanting to underscore Hudgins’s frailty. To make the point that the butler no longer served in the traditional sense. That despite his rising and dressing the part each day, he did little more than answer the door when he was able to hear it, which was becoming less and less frequent. Hudgins had earned a retirement of sorts, comfortable and quiet. Could the Scotsman not see it?

“I require a complete accounting of the items of value in several rooms of the house,” Warnick said. “Paintings, furniture, sculpture, silver . . .” He trailed off, then added, “Carpets.”

What on earth? Why? Lily’s brow furrowed.

“Of course, Your Grace,” the butler replied.

“Not all the rooms, you understand. Only the critical locations. The main receiving rooms, the sitting rooms, the library, the conservatory, and this one.”

“Of course, Your Grace.”

“I should think it would take you no longer than a month to produce such an accounting. I should like it to be as thorough as possible.”

It should not take the man more than a week, honestly, but Lily did not say as much.

“That should be a fine amount of time,” Hudgins replied.

“Excellent. That is all.”

“Your Grace.” Hudgins bowed ever so slightly, and doddered out of the room, Lily watching, waiting for him to finally, finally close the door behind him before she turned on the duke.

“For a man who is so keen to eschew a title, you certainly enjoy ordering the staff about,” she said, approaching him once more. “What an inane request! A full accounting of the contents of the house. You’ve estates valued at literally millions of pounds, Your Grace. And ham.”

She hadn’t meant to say the last bit.

He tilted his head. “Did you say ham?”

She shook her head. “It’s irrelevant. What do you care what is on the walls of the sitting room in a home you did not know existed last week?”

“I don’t,” he said.

She went on, barely hearing the reply. “Not to mention the tedium of such a task—he’ll be occupying each of those rooms for days, considering his unwillingness to end his servitude and live out his life in—” She stopped.

He tossed a piece of ham to the dog on his left.

“Oh,” she said.

And a crust of bread to the one on his right.

“The sitting rooms. The receiving rooms. The library. Here.” He did not reply. “All rooms with comfortable furniture. A month to catalogue the contents.”

“He is a proud man. There’s no need for him to know he’s been pastured.”

She blinked. “That was kind of you.”

“Don’t worry. I shall continue to play the beast with you.” One large hand stroked over a dog’s head, and Lily found herself transfixed by it—by its sun weathered skin and the long white scar that began an inch below his first knuckle. She stared at it for a long moment, wondering if it was warm. Knowing it was. “Tell me, is it just the old man? Or do all the servants overlook you?”

She lifted her chin, hating that he’d noticed. “I don’t know what you mean.”

He watched her for a long moment before lifting the parcel from the table. She watched as he slid one long finger beneath the wax seal and opened it, extracting a sheaf of papers.

“I thought you did not read your correspondence.”

“Be careful, Lillian,” he said. “You do not wish for me to ignore this particular missive.”

Her heart began to pound. “Why?”

He set it aside, far enough away that she could not see it. “I wrote to Settlesworth after you apprised me of your plans.”

She caught her breath. “My funds.”

“My funds, if we’re being honest.”

She cut him a look. “For nine days.”

He sat back in his chair. “Have you never heard of catching more flies with honey?”

“I’ve never understood why one need catch a fly,” she said, deliberately pasting a wide, winning smile on her face. “But it is done, then. I shall hereafter think of you as a very large insect.” She pointed to the papers. “Why are my funds of interest?”

He set a hand on the stack. “At first, it was just that. Interest.”

Her gaze lingered on that great, bronzed hand on the document that somehow seemed to feel more important than anything in the world. That document that clarified her plans for freedom. She was so distracted by the promise of that paper that she nearly didn’t hear it. The past tense.

Her attention snapped to him, to his brown eyes, watching her carefully, unsettlingly. “And then what?”

He made a show of feeding a piece of toast to one of the dogs. Hardy, she thought. No. Angus. It didn’t matter. “I met a man last evening. Pompous and arrogant and obnoxious beyond words.”

Her heart pounded with devastating speed. “Are you certain you were not looking into a mirror?”

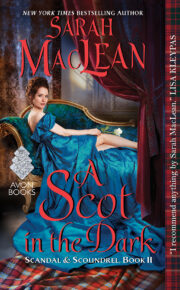

"A Scot in the Dark" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Scot in the Dark". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Scot in the Dark" друзьям в соцсетях.