Alec would carry him to the altar if necessary.

“We have nine days,” he said.

“To convince a man to take a risk on my scandal before all the world has truly witnessed it.”

“To convince a man that you are prize enough to ignore it.”

Lily turned, grey eyes flashing. “Prize.”

“Beauty and money. Things that make the world go round.” Not just those things, he wanted to say. More.

She nodded. “Before the painting is revealed. Not after.”

He opened his mouth to reply, but did not have a good answer. Of course before. Once she was nude in front of the world, she would be—

“Before my shame is thoroughly public,” she said, softly. With conviction. “Not after.”

He ignored the topic, instead saying, “Marriage gives you everything you wish for, lass.”

“How do you know that for which I wish?”

“I know what a woman wants out of life.” He found himself unable to meet her gaze. “It is marriage. Not money.”

She gave a little huff of laughter. “Well, any woman worth her salt wants both.”

He had her. “You’ll get both. Just as you wanted.”

“I wanted to marry for love.”

He recoiled from the very idea. Love was a ridiculous goal—one that was not only implausible but nonexistent. He knew that better than anyone. But Alec had a sister, and so he knew a thing or two about women—and knew, without question, that they believed in the great fallacy of the heart. So he lied to her. “Then we shall find you someone to love.”

She faced him then, tilting her head and watching him as though he were a creature under glass, fascinating and disgusting all at once. “That’s impossible.”

“Why?”

She lifted one shoulder and lowered it. “Because love is for the lucky among us.”

“What does that mean?” he said, her words rioting through him, unwelcome in their eerie truth.

“Only that I am not counted among the lucky. Everyone I have ever loved has left.”

He did not have time to reply, because she was through the door and gone, leaving him with his dogs, the words echoing in the empty room.

Englishwomen were supposed to be meek and biddable.

No one had told Lillian Hargrove such a thing, apparently.

When Alec had told her he was willing to give her a dowry that would get her married to any man she chose, it had occurred to him that she might embarrass him with thanks. After all, twenty-five thousand pounds was a king’s fortune. Several kings’ fortunes. Enough to buy her and the man of her choosing—whoever that was—the life she wanted. An approximation of the love she’d desired.

Granted, Lillian Hargrove was not the swooning type, but the woman would not have been out of bounds to be grateful. A tear or two would not have been unexpected.

Instead, she’d declined the offer.

He’d left her alone for the day, giving her time to change her mind—to come to terms with the idea and realize that his decision had been benevolent if nothing else. After all, she’d wanted marriage once—albeit with an utter ass—and if she considered his solution, Alec was certain she would agree it was best.

These disastrous events could end with marriage and children and the kind of security of which women dreamed.

I am not counted among the lucky.

Bollocks. Luck changed.

If the woman wanted love, she would get it, dammit. He might not believe in it, but he’d will it into being if need be.

He was her guardian and he would play the role, dammit. He would repair her reputation, and he would return to Scotland. And she would be another’s problem. And that would be that.

They had no choice. There was no way to run from the painting, unless she was willing to live life as a hermit. She certainly couldn’t spend the rest of her life rattling around number 45 Berkeley Square, a ward of the dukedom. She was too old to be a ward now—what would it look like when she was forty? Sixty?

It was ridiculous. She would no doubt see that.

Alec had arrived early to the afternoon meal with plans to read his correspondence until she arrived, preferably with an apology and sense on her lips.

After a quarter of an hour, he called for his luncheon. After a half an hour, he finished his letters, but remained with them, pretending to read, not wanting her to think he was waiting for her. After three quarters of an hour, he called for a second meal, as the first had grown cold in the waiting.

And after an hour, he’d called for Hudgins, who took another ten minutes to arrive at a virtual crawl.

“Is Miss Hargrove ill?” he asked the moment the man entered the room.

“Not to my knowledge,” Hudgins replied. “Shall I fetch her?”

Alec imagined that it would take the old man the same amount of time to reach Lily’s rooms as it would take Alec to search the entire house. And so he declined the offer and did just that.

She was not in the kitchens or the library, the conservatory or any of the sitting rooms. He climbed the stairs and began to search the bedchambers, beginning with the floor where he slept in the suite that had been described to him as “the duke’s rooms.” Sharing the corridor were door after door of perfectly neat, beautifully appointed, large, airy, clearly unused spaces. How many people were supposed to live in this damn house?

And where was Lily’s chamber if it was not among these?

He climbed to the third floor, imagining that he would find rooms similar in size to his own, massive and filled with her things. It occurred to him that there was nothing in the common areas of the house that indicated that she lived here at all. In the two days that he had shared the space, he hadn’t seen a single thing out of place. A book left on a side table. A teacup. A shawl.

Hell, Cate produced trails of items throughout the Scottish keep, as though she were leaving breadcrumbs in the forest. He’d just assumed all women did the same.

The third floor was darker than the second, the hallway narrower. He opened the first door to discover what must have been a nursery or a schoolroom at some point, a large room with a lingering scent of wood and slate, golden shafts of afternoon light revealing dust dancing in the space. He closed the door and headed down the dim corridor, where a young maid replaced candles in a nearby sconce.

“Pardon me,” he said, and whether it was the Scots burr or the polite words or the fact that he was nearly two feet taller than she was, he shocked the hell out of the girl, who nearly came off the floor at the sound.

“Your—Your Grace?” she stammered, dropping into a curtsy worthy of a meeting with the Queen.

He smiled down at her, hoping to put her at ease. She shrank back toward the wall. He did the same, to the opposite side, suddenly deeply conscious of the fact that he was so out of place in the narrow space. Wishing he were smaller, as he always did in this godforsaken country, where he threatened to crush furniture like matchsticks.

Pushing the thoughts to the side, Alec returned to the matter at hand. “Which is Miss Lillian’s chamber?”

The girl’s eyes went even wider, and Alec immediately understood. “I am not planning anything nefarious, lass. I’m simply looking for her.”

The girl shook her head. “She’s gone.”

At first, the words did not make sense. “She’s what?”

“Gone,” the girl blurted. “She’s left.”

“When did she leave?”

“This morning, sir.” After their disastrous breakfast.

“When will she be back?”

Those wide eyes gleamed white. “Never, Your Grace.”

Well. He did not like the idea of that. “Show me her chamber.”

She immediately obeyed, walked him down the turning hallway, all the way to the back corner of the house—to the place where the servants’ stairs climbed in narrow twists to their chambers on the upper levels of the house. To such a strange location in the home that he nearly stopped her to repeat his original request, certain he’d terrified the young woman into miscomprehension.

But he hadn’t. She knocked on a barely there door and opened it a crack, immediately leaping back to allow him entry.

“Thank you.”

“You—you’re welcome,” she stuttered, the surprise in her voice leaving Alec hating this country anew, with its ridiculous rules about gratitude and the servant class. A man thanked those who helped him, no matter their station. Hell. Because of their station.

“You are free to go,” he said softly, pushing the door open, revealing Lillian’s quarters, tiny and tucked away, so small that the door did not open all the way, instead catching on the foot of the little bed.

One side of the room shrank beneath a deeply sloped ceiling, beyond which the servants’ stairs climbed, threatening the entire space with a sense of deep, abiding claustrophobia. The sunlight that had streamed into the nursery made the tiny room warm, but that could also have been the result of its contents.

Here were all of Lillian’s things, the breadcrumbs that were missing from the forest of the rest of the house: books piled everywhere; several baskets of needlepoint, filled with threads in a rainbow of colors; a little wooden hammock overflowing with old newspapers; an easel with a half-painted view of tile rooftops and trees in spring—the view that lived beyond the narrow little window that dwarfed the opposite wall.

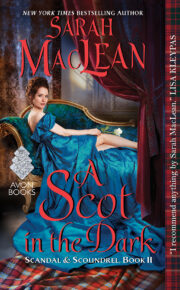

"A Scot in the Dark" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Scot in the Dark". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Scot in the Dark" друзьям в соцсетях.