‘Of course – every week! He writes such lovely letters – really long ones, and full of–’

‘But darling, you mustn’t! It’s absolutely out of the question!’ Anne was agitated. ‘Not only is it very improper for an unmarried girl to carry on a correspondence with a man, but it could be construed as treasonable! Don’t you understand that he’s officially an enemy now? There’s no doubt he reports regularly to Bonaparte, and anything you may happen to tell him will be passed on that way.’

Lolya’s eyes narrowed with temper. ‘Don’t dare to call my darling a spy!’ she said hotly.

‘Lolya, that’s his job! That’s what he was sent to Russia for!’

‘You don’t understand! Just because he’s French, you think he must be wicked – but he hates Napoleon as much as we do! All he wants is peace between our two countries so that we can be together and get married. He hates war!’

Anne looked at her despairingly. ‘Don’t you understand, he’s bound to say that so as to lull your suspicions, and make you talk more freely? Oh Lolya, what have you been telling him?’

Her cheeks were bright. ‘Nothing!’ she said angrily. ‘How could you think it? Don’t you think I know better than to give away secrets? Even if I knew any,’ she added with a brittle laugh. ‘Who would tell a chit of a girl like me anything important?’

‘I don’t believe you would deliberately say anything that would help the enemy – of course I don’t!’ Anne said. ‘But consider, darling – your father is a senior diplomat, and your uncle, with whom you are staying, owns the biggest munitions factory in Russia. There’s no knowing what use even an innocent piece of information might be put to.’

‘Oh, you’re just like all the rest,’ Lolya said, turning away. ‘I’m disappointed in you, Anna Petrovna. I would have thought in your position, you’d be a bit more understanding!’

The least useful thing in the present situation would be to alienate Lolya, and lose her confidence. Anne tried to soothe her. ‘I do understand. I don’t want to make you think badly of Colonel Duvierge – only to be careful. Lolya, he has no right to endanger you by asking for this correspondence! Don’t you see? It’s not the action of a man in love.’

‘Of course he loves me! He can’t live without me, that’s why he wants me to write to him!’ Lolya retorted.

‘A responsible man would never ask the woman he loved to do something that might compromise her. Don’t you understand that?’

‘It’s you who doesn’t understand! You don’t know anything about love! I thought you were different, but you’re just like the rest after all!’

‘Lolya, listen to me–’

‘I won’t hear any more. You’re just trying to poison me against him!’

‘Listen to me! It’s you I’m concerned with, and your safety! All the letters which leave from the post office in this city are opened and read by the Governor’s official. At least while you are in Moscow, you mustn’t write to Colonel Duvierge! Please, Lolya, try to understand! Even if the letter were the most innocent thing in the world, the very fact that you were writing to a senior member of the French Embassy would be considered a suspicious circumstance.’ Lolya regarded her sulkily, but said nothing. ‘Please, promise me you won’t write to him from here.’

There was a long silence, while Lolya’s pride fought with her basic common sense, and her old regard for Anne’s judgement.

‘Oh, very well,’ she said at last, ungraciously. ‘If it will stop you fussing.’

‘Thank you,’ Anne said quickly, feeling a rush of enormous relief. It was a concession; now she must turn her thoughts towards how to tackle the rest of the problem.

But the strain of the last few moments seemed to have affected her oddly: she felt her pulse beating fast all over her body, and her hands were cold and damp.

‘I think it’s very hard of you to lecture me,’ Lolya was grumbling, ‘considering I braved everyone’s opinion to come here and see you..’

Anne couldn’t listen to her. She felt rather sick, and the room seemed to be waxing and waning before her eyes. She put out a hand to Lolya, who suddenly seemed very far away, as if at the other end of a tunnel.

‘I don’t think–’ Anne began with difficulty; but a roaring drowned what she was going to say, and as Lolya’s surprised face turned towards her, for the first time in her life, Anne fainted.

The Emperor’s visit lasted six days, and during that time the patriotic fervour which was endemic to Moscow erupted into near-hysteria, which resulted in wealthy merchants accidentally pledging huge sums of roubles for the war effort, and wealthy dvoriane stripping their estates of serfs, and even their houses of servants, to provide a militia for the support of the regular troops and the defence of Moscow.

The Emperor, who had entered Moscow looking distinctly worried, left it with tears of gratitude. Deeply touched by the fervent loyalty of the Muscovites, who were traditionally rather cool and critical, his parting words to Governor Rostopchin were to give him authority to act in any way he thought fit, should Napoleon ever, inconceivably, reach the gates of Moscow. ‘Who can predict events? I rely on you entirely,’ he said, and drove away to visit his sister Catherine, Rostopchin’s patroness, at Tver on his way to St Petersburg.

Lolya’s visit to Moscow lasted three weeks, and Anne saw her often. The subject of Colonel Duvierge was hardly mentioned between them again. Lolya generously set aside their difference of opinion, and they had some very pleasant outings. Anne met Shoora several times out and about in public places, but she would not visit her in her home. Anne found this hurtful, but saw in it no malice, only the results of her upbringing under Vera Borisovna.

Anne and Lolya parted on good terms, with kisses and promises of seeing each other again soon, as Lolya left with her aunt and cousin to visit friends at their dacha in Podolsk, about twenty-five miles from Moscow.

Basil left Moscow at the same time, to attend a house party given by the Grand Duchess Catherine, with whom he was on very good terms. He took Rose, her god daughter, with him. Anne was invited, but declined in view of the fact that the theatre company, including Jean-Luc, had been invited to perform several plays for the guests during the stay. Anne pleaded ill health as an excuse which would not offend the Grand Duchess, and Basil, seeing that she did look rather pale and preoccupied, accepted it, and even offered some unexpectedly warm words of sympathy.

‘It’s probably only the heat,’ Anne said. ‘I shall be all right once the cooler weather begins.’

‘Why don’t you go down to the country?’ Basil said. ‘Moscow is impossible in August. Go down to the dacha at Fili.’

‘I might,’ she said. ‘Don’t worry about me. Take care of Rose – see she does her exercises.’

‘Of course I will.’

Left alone at Byeloskoye, Anne spent the first few days quietly, walking in the gardens, sitting under the deep shade of the old medlar, pondering her situation. It was different, of course, from last time: there was more of pleasure now, and less of apprehension – but still it was a matter for concern. There seemed, at least, no doubt about it this time. Apart from the fainting fit, she had felt nausea several times on waking in the morning, and a second flux had not begun when it was due. She must have conceived some time during her stay in Vilna in June.

But what to do about it was beyond her to decide. She was married to Basil Andreyevitch. To leave his official protection would place her outside society, and she had already tasted, in Shoora’s refusal to visit her, the aloes of being an outcast. Not only that, but it would bring shame on Rose and on the unborn child. She trusted Nikolai absolutely to take care of her in every physical and emotional way, but even his protection could not change the rules of society.

She could think of nothing to do, but to do nothing. Inside her body, the seed he had planted had begun to grow. She was with child to her love. For the moment, she wanted nothing but to enjoy it in sweet secrecy. Eventually some decision must be made, some action taken; but not now, not yet.

News came regularly from Nikolai. Tolly’s strategy of withdrawal was doing just what it was intended to do – slowing down Napoleon’s advance, weakening his forces and lowering their morale by harrying their flanks, and increasing day by day the problem of feeding and supplying the vast body of men he had brought with him into Russia.

After spending, inexplicably, more than two weeks at Vilna, Napoleon had left on the 16th of July and advanced north-east to Sventsiany, and then turned eastwards towards Vitebsk. He had marched his men fast through the terrible country: marshes into which they sank to the knees; dense forests of fir which scratched their faces and pulled at their clothes; bare roads where the dust rose so thick that the weary, hungry men could only find their way by following the sound of the drummer boys at the head of each section. By day the sun beat down mercilessly on men whose woollen uniforms had been designed for more temperate climates; by night fierce hailstorms beat down on their bivouacs, and the rapid changes of temperature brought on agues and lung sickness.

They marched so fast that their supply train was left far behind, and they had scant time to forage, even if there had been anything to find. But Tolly’s army was marching before them, stripping the country as it went. All the Grande Armée found was deserted, ruined villages; and those who strayed too far from the road in a desperate search for food were picked off by the Cossacks, or slaughtered by the few native Russians who remained in the woods and more distant hamlets.

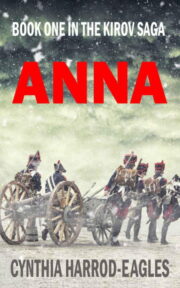

"Anna" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Anna". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Anna" друзьям в соцсетях.