‘Yes, of course. And the knife, and the pistol. But don’t worry – we’ll be all right. It’s an adventure, as Rose says.’

Anne kissed her daughter, trying to appear casual, for her sake. ‘Goodbye, darling. Do just what Jean – what Zho-Zho tells you. I’ll see you again soon.’

Rose kissed her goodbye without concern; but when she turned to her father and saw his expression she was frightened, and turned back to fling her arms round her mother’s neck. Anne soothed her as best she could, but when at last she released the arms from round her neck, Rose’s lip was quivering. There had been too many departures lately; and Mademoiselle had never come back. Rose didn’t ask about Mademoiselle… or Nyanya, or her cat. Glad enough that she still had Mielka and Zho-Zho, she had sooner trust to silence to restore her, some time in the future, to her normal life.

Anne turned her head away while Basil said goodbye to Jean-Luc; and then the porter opened the gates, and they slipped out into the grey, twilit street. As the gate closed, there was nothing to be seen but a peasant woman leading her child on a scruffy pony.

‘They’ll be all right,’ Anne said as they turned away.

‘Yes,’ said Basil.

Their voices revealed that she believed it at last, just as he ceased to.

The response to the Governor’s appeal was magnificent. A huge mob of men and women tramped the three miles out of the city to the Hill of Salutation, armed with pitchforks, scythes, axes, kitchen knives, clubs, even a few rusty pikes and muskets, ready to defend with their lives the city which had nurtured them. They waited there all day; but no one came. They saw no sign of the Russian army they had been called out to support, no sign of the French army they had been summoned to defeat. There was no sign, either, of the Governor who had promised to meet them there. At sunset they gave it up, and began to drift back to the city; and as the sky darkened, the western horizon was seen to be aglow not only with the setting sun, but with the bivouac fires of the two armies, just out of sight over the rise.

A steady stream of refugees continued.to pour into the city, peasants from the land over which the French had already marched, and were expected to march, and wounded soldiers from the battle, who could find no succour anywhere along the road. The stories they told did nothing to raise the spirits of the Muscovites who had been ready to fight for their city. The army was still in retreat, they said, and showed no sign yet of stopping to make a stand of it. If there were to be a battle, it looked like being under the very walls of the city.

That night the Governor issued another proclamation, copies of which were seeded all over the city. He gave no explanation of what had happened that day; only said that early the next morning he would ride out to meet with Prince Kutuzov and discuss with him how finally to destroy the Villain. The proclamation did nothing to calm anyone’s fears. There had been too many contradictory rumours. That night the taverns were full to overflowing, and the darkness was made hideous by drunken revelries, and the sounds of smashing glass and splintering wood as the revellers turned from carousing to looting.

At Byeloskoye, the day had dragged by. It was unnaturally quiet in the streets, except for the distant sounds of wheels, and the shuffling tramp of wounded soldiers making their way through the streets to the hospital. Anne could not settle to any occupation, but continually got up and walked about, thinking of Rose, wondering about the fate of poor Parmoutier, remembering Sergei, longing for news of Nikolai.

Rested now after her journey, she was feeling physically well and strong, but restless with the need for action. She remembered this stage from her previous pregnancy – a good time, when her body had adjusted to its new condition, and she was filled with energy and a sense of well-being. She ought to have told Nikolai; she wished she had told him. She supposed at some point she would have to tell Basil, but she would not do so yet. She hardly showed yet, and with a few extra petticoats…

She persuaded Basil to go through his precious possessions and choose the most essential which could be loaded into one carriage. When they fled, they would be able to take only the bare minimum.

‘But how can I choose?’ he cried. ‘How can I leave anything behind? It isn’t just the valuables – it’s the works of art. They’re irreplaceable! I’ve seen looters at work before. They take gold and jewels and furs, but paintings and statues they simply destroy, like wanton children. How can I leave those things to them?’

Anne shrugged. ‘That’s up to you.’

It was after dark when a banging at the house door startled them both. For some time they had been listening subconsciously to the distant, dangerous sounds of the city; in the streets immediately surrounding the house, there was an unnatural quiet. They strained their ears to hear as Mikhailo went slowly to answer it, spoke a few words to someone, and then came painfully slowly upstairs.

‘A messenger from the Governor, Barina, with a letter for you.’

Anne opened it with suddenly nervous fingers.

My own love, I am taking the opportunity of sending this to you by military courier, so I must be brief. We have arrived at Fili; the French are not far behind us. Bennigsen wants us to make our stand here, but there are grave objections to that. If we do not stand, we must retreat through the city. I will send word tomorrow, as soon as I know what is decided, but hold yourself ready to leave at any time.

When she told him the substance of it, Basil was thrown into a panic. ‘That’s it! I’m leaving now! I’m not going to wait here for the French to overtake us.’

‘Don’t be a fool. You can’t leave now. Have some sense, for God’s sake! We must wait until tomorrow.’

‘Tomorrow! You’re mad! Don’t you read what he says? The French are close behind them.’

‘We must wait to hear if they are going to make a stand.’

‘Make a stand!’ He laughed too shrilly. ‘They’ve been retreating for months – why should they stop now? Tomorrow will be too late – the army will come through with the French right on their heels, and we’ll be caught between them! I’m leaving now, while there’s still time!’

He was up and heading for the door; but now she had heard from Nikolai, an extraordinary calm had come over Anne. She felt no fear, no sense of haste. He was nearby, and would take care of her.

‘Listen to me, Basil,’ she said. ‘We won’t be the only people to receive this news. Everyone’s going to be out in the streets, hoping to get away with as many of their belongings as they can save. You know there’s looting already in the city. If you take those horses out there now, you’ll be set on and robbed, and the horses will be stolen. You’ll have no chance.’

‘More chance than tomorrow,’ he retorted from the door.

‘If there is another retreat, once the army starts to come through, people will be so frightened and desperate, they’ll want nothing more than to save their own skins. They won’t have time to think about anything else. They’ll run like chickens to get out of the city before the French arrive. You’ll be able to drive out in perfect safety. You’ll have the protection of the entire army, after all.’

‘You’re mad,’ he said. ‘Quite mad. I know what it is – you want to wait for your lover. You don’t want to leave before he gets here. Well, that’s your business! I’m not waiting around to lose everything, including my life! I’m going now, while there’s a chance. You can come with me, or you can stay, just as you please.’ And he was gone down the stairs, yelling for the servants.

‘Basil, for God’s sake–’ she called after him, pushing herself up out of the chair. She heard his voice from the hallway.

‘Get those horses put to in the carriage we packed today. Right away! We’re leaving!’

Anne ran after him, pattering down the stairs, really worried now. ‘No, Basil, I forbid it! You’ll ruin everything!’

He turned at the courtyard door. ‘Ruin your pretty plans, maybe,’ he said fiercely. ‘That’s none of my concern. I’m getting out.’ He shouted out into the yard, ‘Get on with it, man! Hurry up!’

‘They’re my horses!’ she said desperately, catching at his sleeve. ‘You shan’t take them.’

‘Yours! Who bought them? Who paid for them? Get away from me!’ He slapped her hand away, and went out into the courtyard. Anne followed, instinctively pressing her hands to her belly.

Outside in the courtyard she saw the horses were being led out towards the waiting carriage. She caught up with Basil again.

‘Take one, then! Not both of them! Leave me one, for God’s sake!’

He shook her off impatiently. ‘Don’t be a fool – one horse can’t pull that load!’ Then he seemed to understand what she was saying. ‘What? Do you mean you’re not coming with me?’

She shook her head. ‘Not now. I can’t.’ He stared at her in astonishment and anger. ‘Leave me one horse, for God’s sake!’

They were backing them up to either side of the pole, now. She saw Basil hesitate, considering; but whether he would have relented or not she would never know. There was a flare of torchlight in the street outside the gates, and someone rattled them hard with a stick, and shouted harshly, ‘Police! Open the gates! Come on, now, open up! This is the Governor’s business!’

Anne whirled round, white with foreknowledge. ‘Take the horses back! Hide them! Quickly!’

But already it was too late. As the porter backed away shaking his head, one of the men reached through, grabbing him by the front of his tunic and jerking him violently up against the gate. He cried out as his face hit the bars, and the key on its iron ring fell nervelessly from his hand. Another hand came through and snatched it up. The porter was released and staggered back, slumping against the wall, putting his hands up to his bleeding face; the gates crashed back, and the men came surging through.

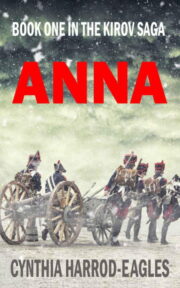

"Anna" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Anna". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Anna" друзьям в соцсетях.