Moscow burned for almost three days. The fire in Kitai-Gorod was only the beginning, for even while French grenadiers were hurrying to the scene, dragging goods out of the warehouses and fighting to contain the blaze, fuses were smouldering in other parts of the city. Every few hours an explosion would signal an outbreak in yet another district. By dawn on the 16th, the fires were out of control, fanned by a strong wind which, by changing direction several times during the next two days, ensured that more and more buildings caught and were consumed.

The Russian army, moving crablike, slowly south and west around the city, travelled by the light of the blaze. During the night of the 16th it was so bright it was possible to read by it six or seven miles away. The whole horizon glowed a lurid, ghastly orange-red; by day the smoke hung over Moscow like black storm clouds. The task of the French fire-fighters within the stricken city was impossible: they soon discovered what the Muscovites of course knew – that even the handsome palaces of the rich were in fact built of wood, with nothing but a thin facade of stone, marble, or stucco, insufficient to stop them, too, from catching fire and burning fiercely.

The army marched mostly in silence. There was nothing cheering in that distant glow, or the thought that the holy city was being devoured. It was thin comfort to know that it would not now offer shelter to the French; a little more comfort to know that the French advance guard had been thoroughly fooled by the Cossacks and were even now following an imaginary army down the road towards Ryazan.

In the early hours of the 18th, rain began to fall, growing heavier and more persistent as the day went on, and extinguishing the lurid glare of the fire on the horizon. Travelling that day was miserable: low clouds closed in the horizon, and shrouded everything in a grey twilight; the rain was cold and unrelenting. The columns first splashed, then squelched, and finally laboured through slippery mud. The horses laid back their ears and shivered, their coats flat and dark with rain, as they hauled the heavy caissons and wagons along the rutted road. Ditches became fast-running streams, sometimes overflowing across the road in a tea-coloured flood. By the time they arrived at last at Podolsk on the Tula Road, everyone was thoroughly soaked, chilled and splashed with sticky mud.

Kirov sent Adonis on ahead to secure some kind of lodgings for them, for he was worried about Anne, who had been increasingly silent as the day went on. She was suffering, he thought, from a reaction – and it was not to be wondered at. The things she had witnessed in the last month would have been enough to destroy a weaker woman. She drooped in the saddle, rain streaming from her collar and the brim of her hat, tendrils of soaked hair dripping on her cheeks. Her condition was only less pitiable than Pauline’s, who was suffering, in addition to everything else, with severe saddle soreness from the unaccustomed cross-saddle position.

Adonis met them on the outskirts of the town, and directed them by a side road away from the centre to a little inn on the back road to Kolomna. Here, thanks to Adonis’s threatening appearance and his liberal handling of his master’s purse, they were received kindly, and given a decent room, with a small private sitting-room attached, in which a birch-log fire was burning, still a little fitfully, under the chimney.

‘They’ve promised a truckle bed in here for the maid,’ Adonis announced, going in ahead of them to stir up the fire.

‘And what about you?’ Kirov enquired ironically. ‘Or didn’t you think to ask?’

Adonis gave one of his equivocal grimaces. ‘I’ll sleep with the horses. I don’t trust anyone, not this close to Moscow. But don’t worry – I know how to make myself comfortable.’

Pauline, her fingers stiff from cold, but simply grateful not to be sitting down, was helping Anne to take off her sodden cloak and hat. The room was musty-smelling and chilly, for the fire wouldn’t draw properly: even as Adonis poked at it, a spat of rain came down the chimney and sizzled on the logs, sending a cloud of pale smoke out into the room.

‘The wood’s damp,’ Adonis announced. ‘Have you got your flask there, Colonel?’

A capful of vodka thrown into the flames caused a minor explosion but made them burn up bright and blue for an instant; and soon there was a cheerful sound of crackling from the logs. Kirov looked at his drooping love and her numb-fingered maid, and took pity.

‘Pauline, go next door and get out of your wet clothes. I’ll take care of your mistress. Go on, now, don’t argue with me. Adonis, do you think you can get them to send up some hot wine?’

When they were alone again, Kirov sat Anne down by the fire, and knelt before her to pull off her wet boots and stockings, and to chafe her feet with a rough towel. She blinked with pleasure at the returning warmth, and then bent her head while Nikolai dried her hair.

‘I never thought,’ she said, ‘that I would ever have you at my feet like this.’

He smiled, and started on the buttons of her jacket. ‘That’s better! Your spirits aren’t completely quenched, then?’

She looked round the dim little room with something like pleasure. ‘No, not quenched. Everything that’s happened seems to narrow my vision, I’m glad just to be with you, and out of the rain. I can’t seem to care about anything else very much.’

He kissed the end of her cold nose. ‘As soon as I’ve got you dry. I’m going to put you to bed and give you a little hot supper, and then I expect you to sleep the clock round.’

‘You’re so kind to me.’ Her eyes smiled sleepily at him. ‘I don’t think I’ll find that at all difficult.’

The next morning, Anne was still asleep when Kirov set out from the inn to ride to headquarters and report. Scouts had already been up to the Sparrow Hill that morning to look down on the ruins of Moscow. The rain had extinguished most of the fire, leaving a blackened, smouldering mess of beams and rubble. About two thirds of the old city had been destroyed. It was a sobering thought.

‘It looks as though the Kremlin is more or less untouched, though,’ Toll told him, with a mixture of relief and regret. ‘So Napoleon will still have a palace to live in.’

‘What are the plans for us now? Do we stay here?’

‘Not if our Tolly can help it. We need to be still further west, so that we can cover the two Kaluga roads. Napoleon still thinks we’re heading for Ryazan, but once that ruse falls through, he’s bound to think of Kaluga. We’re going to press the Old Man to push on across country to Troitskoye. It’s between the Old and the New Kaluga Roads, so we can cover them both from there, at a pinch.’

‘It’ll be hard travelling in this weather.’

‘Fathoms of mud,’ Toll agreed with a grin. ‘His Excellency’s favourite going! We’ll try to get him to order the move for tomorrow morning. I don’t suppose there’s any chance of winkling him out today.’

As Kirov was leaving, one of the Prince’s aides, Colonel Kaissarov, came through the room and nodded a distant greeting, and then paused at the door to say casually. ‘Oh, Kirov, by the way – did that messenger find you?’ Kirov looked puzzled. ‘There was a messenger looking for you – civilian – some kind of artisan, from Serpukhov I think.’

Serpukhov was on the Tula road. ‘No, no I didn’t get the message,’ Kirov said.

Kaissarov turned away, saying indifferently, ‘I expect one of the company clerks has it.’ The Prince’s inner circle tended to have a short way with outsiders.

Kirov was back at the inn in the early afternoon, and hurried up to their rooms, sure of bringing Anne news that would cheer her. He found her in the sitting-room, crouched over the fire, which was burning better today, now that the chimney had warmed up.

‘I’ve got a letter for you,’ he greeted her cheerfully, bending over to kiss her cheek. It felt burning hot under his lips, and he straightened to look down at her with consternation. Her eyes were bright, her cheeks painted with fever. ‘You’re ill! What is it, love?’ he said, alarmed.

‘I seem to have caught a cold, I’m afraid,’ she said. ‘Nothing to worry about, Nikolasha. What is this letter? From whom?’

‘It was addressed to me and sent to headquarters,’ he said, unconvinced, but allowing himself to be sidetracked. ‘But when I broke the wafer, I found it was really meant for you. Someone’s been using his wits about the surest way to find you.’

Her face lit. ‘From Jean-Luc? News of Rose?’

He gave it to her, and she turned to the firelight to read it.

First of all, it said, I must tell you that we got safely away. No one troubled us in the least. We reached Podolsk by evening; now I have moved on to Serpukhov.

A family has taken us in – very kind – the Belinskis. He owns a furniture factory; she thinks 1 am clever and amusing. They have a daughter, fifteen, who longs to go on the stage, and a son, eighteen, who longs to join the army: they beg me to tell my adventures over and over. I am very popular as you can imagine!

We are comfortable here, and they love Rose, so 1 don’t see any point in going on further. I shall wait here for news.

We heard that the French took Moscow; and today we heard that it was burning. I pray you both got safely away. I tell Rose you certainly did, but pray send word soon to reassure her. She is well and happy. They have given her a white kitten, and Belinski fils is teaching her the piano.

I send this care of Count Kirov as being the surest way. Everyone always knows where the army is; and he will surely know where you are.Adieu! – De Berthier.

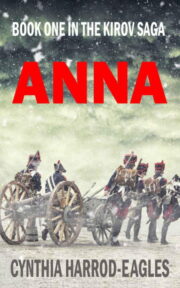

"Anna" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Anna". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Anna" друзьям в соцсетях.