Anne read and re-read this unsatisfactory epistle. There were a hundred things she wanted to know; but at least Rose was safe, and being cared for. The letter was typical of him, she thought, trying to read what was unwritten, between the lines. What had he told these Belinskis? How had he explained his relationship with Rose? Had he hidden the fact that he was French? It maddened her to have to leave her precious child in that man’s protection, and under his influence.

‘Did you read it?’ she asked Nikolai. He nodded. ‘It’s good to know they are safe, at least; but I wish he had gone on to Tula.’

‘Does it occur to you, love, that if he did that, he might find himself separated from Rose? I’m not sure that he would be entirely welcome at the Davidovs’. I don’t suppose Shoora would understand about him and Basil, but Vsevka might thank him and firmly show him the door, especially since he has two unmarried young females in the house.’

‘Yes, Lolya and Kira. He would not care to have them associate with such a man.’

‘By remaining where he is, he can stay with Rose, and tell them what he likes.’

Anne sighed. ‘I’m sure you’re right. We must go and fetch her as soon as possible. Now that her father’s dead – and there’s another thing: how can I tell him about Basil? How can I tell Rose?’

‘I don’t know,’ he said gravely. ‘I think, for the moment, it is better to leave things alone. Send them some non-committal word which will satisfy them for the moment, until we can – Anna? Are you all right?’

She shivered, feeling herself first hot, then cold. ‘I think I have a little of a fever,’ she said.

He touched her brow. ‘I think you have a lot of fever,’ he said, alarmed. ‘I think you had better go straight back to bed.’

Her limbs ached, and the thought of lying down was very tempting. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘perhaps I will.’ But she found she couldn’t get up; Nikolai had to carry her into the bedroom.

The following morning, the army moved out from Podolsk to march the twelve miles or so to Troitskoye. Count Kirov was not with them. Anne’s temperature had climbed all through the day, and by the evening she was plainly very unwell. Adonis, despatched to headquarters in search of a doctor, came back with General Tolly’s personal physician, sent by that kindly soldier with a note expressing his concern.

The physician diagnosed an influenza, and Kirov, whose mind had been running on typhus, smallpox and other such horrors, drew a sigh of relief. ‘Thank heaven!’ he said, and almost smiled.

‘An influenza is not to be taken lightly,’ the doctor reproved him sternly.

‘No, no of course not,’ Kirov murmured, quickly straightening his face.

‘A young and healthy person, with good nursing, should recover from it without permanent disability. But you must take no chances. These are bad times – a lot of infection about, and winter coming on! And there is always pneumonia to think of, my dear sir!’

‘Yes, indeed. I shall be very careful.’

The doctor looked a little mollified. ‘Make sure she’s kept warm at all times, and quiet. Saline draughts until the fever breaks, and then a light diet for the first week. After that, as much nourishing food as she can take. You’ll find she’s rather pulled by it – convalescence can be slow. But in a month or six weeks – I think in two months’ time you may find she is quite herself again.’

‘I understand.’

The doctor looked at him curiously. ‘You know the army is leaving tomorrow? She mustn’t be moved, of course.’

‘No, of course not. I shall speak to the Commander-in-Chief.’ He frowned a moment in thought. ‘If he won’t allow me leave, I shall resign my commission,’ he said finally. ‘I can’t leave her now.’

When the physician had gone, he discovered a sense of relief inside him at the thought of resignation. He was very tired, more tired than he had realised, and the thought of letting go was very pleasant. Everything told him it was time to step out of the current of events, and rest a while.

Anne was very ill – so ill that many times Kirov thought the doctor must have been mistaken in his diagnosis. Her temperature climbed, sinking back a little during the middle of the day, and then rising again towards evening, when she would sometimes become delirious. She complained at first of aching limbs and a severe headache; then she developed an exhausting cough, and her throat became too sore to speak.

It was Adonis, oddly enough, who took charge of the nursing. The innkeeper’s wife inclined to the burning-noxious-vapours-and-swallowing-live-insects school of medicine, which had flourished in the previous century: and Pauline, though willing enough, knew nothing of the business, beyond what her grandmother had once told her – that sick people should lie with their feet higher than their heads so that the infection could drain out of their ears.

This didn’t strike Kirov as very helpful, and he was relieved when Adonis sent her away kindly but firmly, saying that she was not robust, and should not be exposed to the sickness, or he would have two of them on his hands. Pauline was at first scandalised that he, a male, should propose taking care of her lady; but once she learnt that the innkeeper’s wife was to perform the more intimate tasks for her, she relented; and seeing how skilled Adonis was at nursing, she soon ceased to regard him as a male creature at all.

It was Adonis who prepared saline draughts and herbal infusions, and who persuaded the delirious patient to drink them; it was he who propped her up on pillows when she found it hard to breathe, bathed her hands and face with rose-water, and mixed a soothing syrup for her throat. Most of all, it was he who calmed Kirov’s fears by telling him again and again that she was doing very well, and that it really was just an influenza; and dealt, successively, with his master’s fears of smallpox, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and, when the cough began, consumption.

At the end of a week, the fever broke at last, leaving the patient with all the symptoms of a heavy cold, cough and sore throat, which even her distracted lover could believe she might ultimately recover from. It was as well that she did show this improvement, for on the 26th of September the cavalry of the French advance guard, who had several days before realised they were following a party of Cossacks on a wild goose chase, discovered at last where the main Russian army had got to. They began advancing southwards, and Prince Kutuzov, not seeing any need to gratify them by giving battle, gave the order for another withdrawal, towards Kaluga.

This left Podolsk in a rather exposed position, and after a brief consultation between them, Kirov and Adonis agreed that it would be more dangerous to remain where they were than to remove Anne to a safer place.

‘Now the fever’s broken – as long as she’s well wrapped up, and put in a coach of some sort–’ Adonis said.

‘Yes, I agree. But where can we go? We don’t want to travel too far, but we need to be safe.’

‘Somewhere out of the way – off the main roads. I’ll make enquiries, Colonel.’

His enquiries produced a small house on the side road from Voronovo to Kolomna belonging to a local dvorian, whose finances had become so perilous in the hard years leading up to the invasion that he was willing not merely to rent it but even to sell it, and to remove himself at a moment’s notice to the home of a married sister in Tarutino. The deal was rapidly concluded, and Anne was wrapped in a large quantity of warm clothing, and placed in a telega hired for the purpose, and they removed to Litetsk on the same day that the first French company came clattering into Podolsk.

Although only ten miles further on, Litetsk was much more isolated, standing on an unfrequented road, and sheltered from casual view from the road by an exceedingly overgrown park and almost impassable drive. It was very unlikely that any French patrol would even use this road, and still less so that they would think of leaving it to penetrate the tangle of the driveway for any reason.

The four of them settled in, to light the fires, screen the draughts, and make themselves comfortable. The move had exhausted Anne, who was suffering from the usual debilitation of influenza. She slept a great deal, and when awake had no energy for anything but to lie looking at the fire. For the others, the sense of security of Litetsk was enhanced by the knowledge that there was nothing they must or even could do until Anne was well again; after strenuous effort and worry, the reaction caused a depth of relaxation in all of them amounting almost to lethargy.

Nikolai spent his days sitting in a chair by the fire. When Anne slept, he dozed and daydreamed, going over the events of the past, taking stock, repairing the thousand tiny lesions in heart and mind that a full life and an active career had left. He was very tired, and for the first ten days at Litetsk he rarely stirred from his chair; eating and drinking with infantile docility whatever Adonis put before him; caring nothing about the progress of the war; retiring early to bed, to a deep and dreamless sleep.

As Anne grew stronger, and was able to sit up and take notice, so Nikolai recovered too. She was still very weak and pulled, and a little of any activity sufficed her. He sat with her and read to her, played cards with her, but mostly just held her hand and talked to her. At first they talked randomly, of neutral subjects; but they both had a great deal of mourning to do, and there were shocks they had sustained whose effect had been, through necessity, deeply hidden. The time came when it was right for those events to be relived, for the pain to surface and be suffered and dealt with.

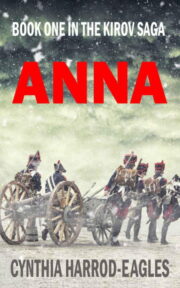

"Anna" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Anna". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Anna" друзьям в соцсетях.