Anne found her legs trembling, and was forced to sit down, taking Rose, who was clinging to her like a marmoset, on to her lap.

‘I am so grateful to you, Madame Belinski,’ she heard herself say in a light, shaky voice which was hardly her own, ‘for taking care of my daughter. I don’t know how I shall ever be able to thank you.’

‘We have enjoyed having her, Madame – and her brother,’ Madame Belinksi said. ‘Or – I suppose I should say, her half-brother?’ A hint of a question mark crept into her voice as the puzzlement surfaced on her painted face. ‘For I see now – excuse my impertinence, madame, but you are much too young to be dear Zho-Zho’s mother! Not, of course,’ she went on, with curiosity strong in her voice, ‘that there’s a great resemblance between him and Rose – but that would be accounted for, perhaps…’

Anne dragged her wits together. So that’s what he had told them! Clever – or was it more devious? ‘Yes, of course – a previous marriage,’ she said vaguely. ‘I dare say he resembles his mother more strongly.’

Nikolai spoke from behind her. ‘I wonder if I might have a word with you – er – Zho-Zho – in private, if Madame Belinski would graciously excuse us?’

‘Of course, of course – please do,’ Madame Belinski smiled and blushed, and Anne guessed that Nikolai was being charming over her shoulder.

‘And then, I’m afraid, we shall have to be taking our leave. I hate to descend on you and leave again so suddenly–’

Madame Belinski looked taken aback. ‘But no, surely not – you will stay to dinner at least? My husband will want to meet you – and the children are out visiting – they will be heartbroken. Oh, surely, after Rose has been with us so long, you will not just take her away helter-skelter like that!’

Nikolai was grave. ‘Madame, I regret deeply the appearance of haste and ingratitude it must present to you. I assure you nothing but the most urgent considerations of national importance would persuade me to leave so precipitately, but where His Majesty’s business is at stake, all else must come second.’

Madame Belinski was flattened by the speech, which contained at least three words she didn’t understand. ‘Oh, of course, of course,’ she whispered meekly. ‘I quite understand.’

‘And I assure you, dear madame, that as soon as the present emergency is over, we will return in order to thank you properly for all the kindness you have shown, and to allow little Rose to visit you again. Indeed, I hope she will often be visiting you. I’m sure she regards you now as her second family.’

These sentiments set Madame Belinski chattering about kindness and obligation, which she directed at Anne as Nikolai took Jean-Luc out of the room – she supposed to tell him about Basil. Anne listened patiently, aware of the great and real debt she owed this kind woman; and feeling guiltily glad that Nikolai had made it possible for them to get away.

It took over an hour to do so, despite the fact that there was very little to pack, for it was very hard to stop madame talking. The Belinskis had given Rose a number of toys and new clothes, and there was the white kitten, too; and then Rose had to say goodbye to all the servants individually. Anne was afraid the rest of the family would come back before they had left, and it would all begin again; but at last they were all squeezed in the carriage, with Rose on Anne’s lap and the kitten on Jean-Luc’s, and they were off.

Jean-Luc had hardly spoken a word since they arrived at the house, and Anne was not very surprised, considering the nature of the news Nikolai had given him. She was surprised when they travelled only another ten miles towards Tula, and stopped at a posting-inn in a village, where Nikolai announced they were to spend the night.

They bespoke rooms, and an early supper; Anne acquired some bread and milk from the kitchen for Rose, and had the pleasure of sitting with her while she ate, and then of bathing her and putting her to bed herself. When she tucked her in, however, she asked for Jean-Luc to come and kiss her goodnight. Anne shrugged inwardly, kissed her daughter, and went downstairs to find him.

She couldn’t help wondering what was going to happen at Tula, if, as Nikolai said, the Davidovs would not admit him to the house. His position was now equivocal, to say the least; and when they settled again in their own home, what then? Without Basil, he had no place in her household, except as Rose’s ‘friend’. How much he really cared for her daughter she was unsure: not enough, she hoped, to make him want to stay near her.

She found Jean-Luc with Nikolai in the coffee room, and delivered Rose’s message.

‘Very well, I’ll go up at once,’ he said. He hesitated a moment as though he would say more, and then shrugged, and left them.

Alone, Anne and Nikolai turned to each other. ‘He told the Belinskis he was Rose’s brother,’ she said.

Nikolai looked grim. ‘It was his solution to a deadly problem,’ he told her. ‘I’ve been talking to him – had it all out of him. He stumbled, you see, though he didn’t know it at first, into a household of the most rabid patriots and Francophobes in the province. If Belinski père had discovered the truth about him, he would have handed him over to the town committee, who would probably have hanged him without further ado. Fortunately for him, his acting skills enabled him to hide any trace of his nationality. His great fear was that Rose would betray him accidentally – but I don’t think they were terribly discerning people.’

‘No,’ Anne said thoughtfully. ‘Poor Jean-Luc. It must have been very bad for him.’

He raised an eyebrow. ‘You feel sorry for him? I thought you hated him unrelentingly.’

She gave a painful smile. ‘I did. But I wonder sometimes… I can see just a little what he must feel. Did you tell him about Basil?’

‘Yes. Also about the Theatre Français leaving with Napoleon’s train: that his old company, to a man, are heading out of Russia as fast as they can go.’

Anne looked puzzled. ‘Why did you tell him that?’

‘Because he needs somewhere to go.’

Anne studied his face carefully. ‘He’s going with them? He does not mind, then, leaving Rose?’

‘Do you want him to stay?’

‘No – of course not – but–’

‘Then be grateful.’ He stood up abruptly and walked to the fireplace, resting one elbow on the chimney-piece, and said, ‘Now that Basil is dead, there is nothing for him here. He will be an embarrassment to you and to himself, besides being a danger to Rose – moral and physical. For her to be in company with a Frenchman now – and later, for her to be under the influence of a known sodomite–’ The brutality of the word made Anne wince and he met her eyes briefly and then turned away to look into the fire. ‘Yes, I put it to him that way, in those words. So he’s decided to go back to Paris, to his own people.’

‘You put it to him?’ she said slowly. ‘What else? Nikolasha – what else?’

He didn’t turn his head but spoke still staring into the fire, his forehead resting against his arm. ‘I threatened him a little, too. Told him that once I married you, I wouldn’t let him see her. I said that if he didn’t go, I would see to it that everyone found out he was French.’ A pause. ‘That would be like sentencing him to death.’

There was a long silence. She looked at his back, and didn’t know what to say, or even to think. All he had said of Jean-Luc was true; yet Jean-Luc had brought Rose safe out of Moscow, and Rose loved him. There was no place for him here now; he must be sent away. Nikolai had done what he did for the best, she thought, but it was not the sort of thing she would have expected of him.

He stirred, as if he had heard her thoughts. ‘I don’t like myself very much at the moment,’ he said.

Jean-Luc left early the next morning, not wishing still to be there when Rose woke. Kirov did his best for him, gave him money and a fur coat and a horse; and wrote him a letter which would get him safely through any Russian military hands into which he might fall. ‘When you get near the French, make sure you destroy it, or they’ll think you’re a spy. You had better buy provisions as you pass through Serpukhov and carry them with you. Travel as fast as you can – stay at the head of the French column. With a good horse, you should get through – but take care of it. If it dies, you die.’

Jean-Luc received everything – money, horse and advice – in hostile silence. Kirov eyed him thoughtfully. ‘It’s for the best,’ he said. ‘When the Grande Armée has gone, it won’t be a good thing to be French.’

‘No. But that isn’t why you want me gone. You don’t give a damn about the safety of my skin.’

‘No – but Anna does. And I care about her – and Rose.’

At the mention of the child, Jean-Luc’s face crumpled for an instant, before he regained control. ‘Take care of her,’ he said. ‘If you let any harm come to her – I may not be able to hurt you in this life, but I’ll pursue you beyond the grave, I swear it.’

‘I’ll take care of her,’ Kirov said gravely. ‘I – I wish you well.’

The mask was in place, and Jean-Luc gave him a smooth and seamless look. ‘God damn you, Count Kirov,’ he said calmly. ‘And God damn Napoleon Bonaparte – if he hadn’t invaded Russia, none of this would have happened.’

‘I think God has damned him already,’ Kirov said. ‘Take care you don’t get caught in the blast.’

It was hard to explain to Rose that Jean-Luc had gone. She accepted it at first, but Anne realised later that it was only because she hadn’t understood, and thought he would be back. When they prepared to leave the inn, she dug in her heels and refused to move. They must wait for Jean-Luc, she declared. They couldn’t go without him.

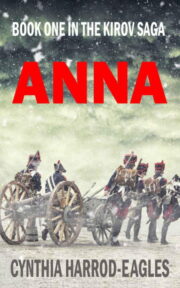

"Anna" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Anna". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Anna" друзьям в соцсетях.