"We will be sailing tomorrow, my lord," the janissary told him.

"The young milord?" Caynan Reis asked.

"Quite shocked to find himself shackled to an oar, my lord, but otherwise unharmed," came the reply.

"See that he remains unharmed. If his manners can be improved, I will consider redeeming him to his family eventually. It seems a shame to lose the ransom." He looked at Tom Southwood. "You look the part," he said dryly. "Are you certain you can fulfill your duties?"

"I can, my lord," the Englishman answered him. "I have taken the name of Osman, in honor of a dear and old friend of my grandmother's who lived in Algiers many, many years ago. He was an astrologer."

Aruj Agha's mouth dropped open. "Osman the Astrologer? The Osman?" He turned to the dey. "My lord, he was very famous, and highly respected." Then he looked at Tom Southwood. "Your grandmother really knew Osman? How?"

"It is a long tale, my lord agha, but I shall happily relate it to you on the long nights we are at sea." Then he said to the dey, "My lord Caynan Reis, may I beg a small boon of you before we depart?"

"What is it, Navigator Osman?" the dey replied.

"My cousin…?" Tom Southwood murmured.

"Still retains her virtue," the dey said dryly. "I am of a mind to be patient with her and so she serves me as my body slave. She is quite unharmed, and will remain so if she continues to behave."

"Thank you, my lord." Tom Southwood bowed, and then remained silent as the agha and the dey discussed the voyage to come. The English captain glanced a final time at India. She nodded her head just imperceptibly at him, indicating that she had heard and was all right. He looked quickly away from her, and just in time, for the agha was ready to leave.

The two men bowed once again to the dey, and then departed the audience hall. The dey settled himself upon his low throne, and nodded to the head eunuch to order the doors opened. India began to wave the fan over him. The dey's secretary, a small, fussy little man appeared, and handed him a long scroll of parchment which was filled with a great deal of writing, none of which she could read. The doorkeepers flung open the doors, and the hall was suddenly filled with a multitude of people, none of whom were, to India's great relief, interested in ogling her carmine-tipped bared nipples.

Caynan Reis handed his secretary the scroll, and said, "Begin."

"The divorced woman, Fatima, and the merchant, Ali Akbar," the dey's secretary said, and when the two stood before the dey, his secretary told them, "First the woman may speak, and then Ali Akbar."

The woman bowed politely. She was neatly but poorly dressed, and far past the flush of her youth. "My lord, I have come to you for justice. Some thirty years ago when I was fourteen, I became Ali Akbar's first wife. I have given him three sons and a daughter. In the ensuing years, Ali Akbar took three more wives, which as you know, my lord, is all the wives allowed under the laws of the prophet. In order to take another woman to wife, Ali Akbar has to discard one of us. I am she he cast aside so he might wed with a thirteen-year-old maid who he hopes will restore his lost virility. I will be honest with you, my lord. I am not unhappy to be free of this man. Whatever love that was between us died years ago. However, Ali Akbar has refused to return to me my bridal portion, which, as you know, my lord, is mine under the laws of the prophet. Without it, I am a beggar at the gates. I have no home. I must beseech strangers for my daily bread. Please help me, my lord. I throw myself upon your gracious mercy."

Caynan Reis looked at Ali Akbar. "Is this true?" he asked.

The merchant squirmed beneath the dark gaze. "My lord," he began nervously, "business has been poor of late, and I have other, more important obligations to meet. Fatima could go and live in her daughter's house, but she prefers to shame me by wandering the streets, and importuning all who will listen with her litany of complaints against me."

"Have you returned your former wife's bridal portion?" the dey demanded sternly.

"No, my lord." The merchant shifted uncomfortably.

"Return it this day." The dey looked to the woman, Fatima. "Do you know how much is owed you, lady?"

"Yes, my lord," she said softly.

"You will tell my secretary," he told her. "And you, Ali Akbar, will not argue the price. The lady appears honest to me. And in punishment for your greed, I order you to purchase a house with a garden for the lady Fatima, and two slaves to serve her. She will be permitted to choose the house and the slaves herself. And you, lady, will cease your public complaints against this man in return."

"My lord, you will ruin me!" the merchant cried, and he shook an angry fist at his former wife.

"And," the dey continued, "you will pay a fine to the sultan's coffers of ten gold pieces, and another ten to the chief mullah of El Sinut in penance for your attempt at flouting the laws of the prophet. While the law allows you to discard one wife for another, it also makes provision to protect such a woman. You broke your word when you refused to honor your betrothal agreement. Any further complaint from your mouth, Ali Akbar, will be met with severe punishment."

The merchant was at last cowed, and bowed to the dey before turning abruptly and leaving the audience chamber.

The woman, Fatima, however, fell to her knees, and kissed the dey's slipper. "Thank you, my lord," she said, tears running down her worn face.

"Do not commit your husband's sin of greed when you seek your own shelter, lady," he warned her. "The sword of justice cuts both ways."

"Yes, my lord," she said, scrambling to her feet and backing away from his presence.

India was absolutely fascinated. For a few moments, she had almost forgotten to ply her fan so the dey would not become overheated. She had thought El Sinut a place where women counted for little, but if she understood it correctly, women were protected under the laws of Islam. Caynan Reis had been kind, firm, and very fair in his handling of the matter of the woman, Fatima, and the merchant, Ali Akbar. The other cases brought before Caynan Reis that day were not half as interesting, but he judged them all with utmost equitableness, it seemed to her.

In midafternoon the dey called a halt to the proceedings and dismissed the remaining people from the audience hall. He had heard almost all of the cases on his secretary's scroll, and would hear the others first the following week. He arose, removing his turban and handing it to India. Then he strode from the chamber. Almost flinging her fan at an attending slave, India hurried after him.

"I am hungry," he told her. "Go to the kitchens and fetch me something to eat, India," he said as they entered his apartment.

"Yes, my lord," she said, putting the small turban upon a table. "Is there anything in particular that you desire?"

"Just food," he told her.

"I can find my way," India told Baba Hassan, and she ran out.

"You will need help," Abu told her in a conciliatory tone when she told him that the dey desired food. "He eats his main meal now in midafternoon, and then naps in the heat of the day. I will send several kitchen slaves with you to carry the food."

"What will you give him?" India asked, curious.

"He is not a heavy eater," Abu said. "I will send a roasted chicken, a bowl of saffroned rice with raisins, a dish of olives, some sliced cucumbers in oil, and bread and fruit." As he spoke, he piled the trays with the items he named, signaling several little kitchen maids to take up the trays and handing India a decanter. "This is a lemon sherbet for the dey to slake his thirst. You may carry it, and the silver goblet."

"The dey does not drink wine?" India asked.

"Wine is forbidden by the prophet, although there are some in Barbary who do not obey the prophet." Abu finished darkly.

India thanked the more cooperative cook, and led her party of serving girls back to the dey's apartment. The sun being high now, however, this meal was taken indoors, and when he had finished eating, he again instructed India to eat from his leftovers when she had stripped him of his garments, sponged him with rose water, and helped him to his couch to rest. This is ridiculous, she thought to herself, but silently followed Caynan Reis's orders. When he lay, apparently dozing, she crept to the table, and, seating herself, began to eat. Abu was not stingy with the food, and she was quickly satisfied. Afterward she carried the trays, one at a time, back to the kitchen. When she returned to the dey's apartments at last, Baba Hassan was awaiting her.

"The dey will sleep until just before sunset, girl," he told her. "You are permitted to rest also now that your duties are completed."

"Where am I to sleep?" she asked him.

The chief eunuch went to a small cupboard, and drew out a narrow mattress he proceeded to unroll. "This will be yours. You are to place it outside of the dey's bedchamber, and sleep there unless he instructs you otherwise. He will call you when he desiresyour service. When he arises, you will find a silk kaftan for him in the cedar cabinet. He has no guests this evening."

She was to sleep on a mat outside Caynan Reis's bedchamber door? It was absolutely ridiculous! But at least she was comfortable, India thought. She was not chained to an oar, seated upon a hard wooden bench on Aruj Agha's galley. Silently India spread the mat Baba Hassan had given her before the dey's bedchamber door and lay down upon it. Soundlessly she wept. This was what her pride had brought her to, and if Adrian died, it would surely be all her fault.

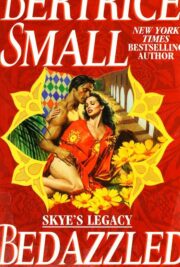

"Bedazzled" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Bedazzled". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Bedazzled" друзьям в соцсетях.