Yunus’s sole response was to chant the shahada, the hymn of the murids, and to let Jamal Eddin climb behind him to ride pillion.

“La ilaha illa Allah. There is no other god but Allah.”

The rest of the horsemen took up the chant, singing at the tops of their voices, drowning out the roar of the river and making the mountain air tremble. The echo rippled down the narrow gorge and reverberated from valley to valley down the immense chain of the Caucasus. It went on forever, and with it the lesson of the imam Shamil, reaching even the most isolated auls. Unity in the service of God was the most precious treasure of the Muslims. Unity was the incarnation of absolute good that justified all sacrifices. No sword, no cup, no treasure in the world was worth risking the disunity of the servants of Allah.

But the image of the sabers in the torrent continued to haunt Jamal Eddin, leaving a great question mark in his mind.

CHAPTER III

The Shadow of God on Earth

“Yunus,” Shamil said after his usual polite greeting, “tell me about my son.”

“Mohammed is the first prophet of Allah, Shamil is the second,” Yunus said, avoiding the question.

The phrase was common among the men of Dagestan, who used it as a greeting, a prayer, and a rallying cry. Declared with hand over heart, it acknowledged the divine mission of the imam and proclaimed the union of his people under his authority. Coming from Yunus, it summed up Shamil’s glory and his successes: the shadow of God spread across the earth.

Nonetheless, Shamil’s spectacular gesture on the bridge at Ghimri had ruined them all.

While his actions had reinforced his image as a saintly man, they had hindered the liberation of the Caucasus. How could one finance a holy war without gold? How could they buy horses, guns, and cannons?

Shamil had nothing.

Avoiding any direct confrontation with the Russians for the time being, he concentrated upon community affairs.

Armed with the axe of justice, flanked by the sabers of his executioners and the muskets of his well-trained troops, he traveled from village to village, preaching the Sharia and keeping his promises to the hypocrites. His injunctions to repent, if they went unheeded, were followed by punishment, as he executed those who disobeyed his laws, the law of God, or the laws of men. He levied heavy fines on those who committed lesser transgressions, filling his coffers anew. In three years, through rigor and terror, he had instituted a system of taxation to which all were subject and imposed a religious, political, and moral code that excluded corruption and formed the basis for a state.

One essential task remained: to drive out the infidels and let liberty triumph.

On this late September day in 1837, Shamil and Yunus rode together, reins slack, avoiding the usual trails as they slowly circled the village of Chirquata. Tucked into the mountain-side, the fortified aul of dilapidated hovels with terraced roofs spread over the hillside. Heavy storm clouds hung over the houses where their families awaited them. Shamil had scarcely had time to watch his children grow up these past three years. He had spent all his time on horseback, like a nomad, leaving his wife and sons in the protection of one community chief or another for weeks, even months, at a time. These long stopovers had permitted Bahou-Messadou to remarry Patimat to the mullah Akbirdil Mohammed al-Kunzakhi, one of the only natives of Kunzakh to have rallied to the murid cause. Shamil’s sister had given her new husband two sons. The eldest was named Hamzat, the name of the imam assassinated by Hadji Murat.

This last separation, the longest, had gone on for eight months. Yunus, who had galloped from village to village to meet the imam, knew at this very moment that Shamil was trying hard to control his impatience. His face was a mask.

Heads lowered, their flanks dark with sweat, the horses nibbled at the rare blades of grass they found between the rocks. The horsemen would let them dry off before taking them to the fountain to drink. They had a good deal to say to each other but spoke sparingly, embarrassed by the soft intimacy of the evening light. Yet they knew each other so well. They had shared everything, from nights of camping out on the banks of raging mountain streams to solitary rides through the snow, the adrenaline-infused waiting period before an attack and the long hours of watch duty beneath a leaden sun outside the Russian forts. Theirs was the communion born of men facing death.

But in forty years of friendship, they had never taken this sort of leisurely ride in the quiet of dusk.

They had matured at the same time, both filled with the same love of liberty and a thirst for God. They were equally attached to those close to them. Yunus’s young wife Zeinab was as precious to him as Fatima was to Shamil. Both of them loved to come home to their wives, and both were equally capable of sacrificing them. Beyond that, they were very different. Black-eyed Yunus had swarthy skin and a long, thin face like the blade of a knife. His pointed beard made it look even thinner. Of medium build, his wiry body projected not power, but a stamina and agility that resulted from years of training himself to push beyond his limits. He seemed as nervous, nimble, and irascible as Shamil seemed leonine, placid, and calm. It was a distribution of roles that gave them an advantage over strangers. Shamil had not chosen Yunus to serve as his eldest son’s tutor, or atalik, by chance. He was a man of honor and a steadfast companion.

Today, as naïb and administrator of Chirquata, Yunus had a matter of importance to discuss with Shamil. Their spies at the nearby fort of Temir-Khan-Chura had just informed him that the padishah Nicholas, the “Great White Czar of the Infidels,” was expected to arrive in these mountains at the end of September. He planned to travel from far-off Saint Petersburg to Tiflis, the capital of Georgia and the seat of the Russian viceroyalty of the Caucasus. During his tour of inspection, he might very well stay at one of the forts along the line. If that were the case, should they resume hostilities? Harass the dogs everywhere? Stage a grand coup? Or profit from this extraordinary visit to negotiate?

That was the subject of their conversation. What game should the humble Shamil of Ghimri employ to conquer the emperor of all the Russias?

“First of all, tell me about him,” murmured the imam, finally breaking the silence.

“Their padishah—”

“No, Jamal Eddin. How do you find him?”

“Almost like you at the same age,” Yunus replied reluctantly.

He could not understand how Shamil, whose wisdom and judgment he admired, could keep asking about his son. A man should never mention his wife or children before a third party. He must not even refer to their existence.

“Almost like me?” Shamil insisted mischievously.

Yunus had no sense of humor. He tried to explain himself seriously.

“Your son is training himself to run long distances, with a pebble in his mouth to force himself to breathe regularly.”

“You’re the one who gave him the pebble?”

“No need, your son knows. He imitates you all the time, in every possible way. He walks barefoot, bare-chested, and on an empty stomach. Like you. He wrestles and practices with the saber, he swims and high jumps. Like you. But he’s still—” Yunus hesitated, searching for the right words.

“Still what?” Shamil repeated, smiling.

Yunus scratched the back of his neck. He was going to say, “still green,” but he restrained himself, thinking that the boy’s father would take it as a reproach or an insult.

“Young.”

“Young? Well, of course he’s young. What do you mean by that? That he’s weak or lacking in courage?”

“Your son is not weak. Sheik Jamaluddin al-Ghumuqi, your own mentor, who is instructing him in the Koran, can tell you about his progress better than I.”

Shamil wouldn’t let it go.

“But you’re the one who’s educating him. I’m listening.”

Yunus sensed Shamil’s dismay at his embarrassment and was afraid that this would lead to a misunderstanding. He decided to speak frankly.

“The imam Shamil should have fifty sons like Jamal Eddin.”

Relieved, Shamil nodded. “And Mohammed Ghazi?”

“The youngest promises to have all his brother’s attributes.”

Shamil savored the information. The subject was closed, and Yunus knew it would not come up again. Finally he worked up the nerve to say, “Two sons are not enough to ensure your lineage. Allah protects them, but if either of them came to harm, what would happen to the imamat?”

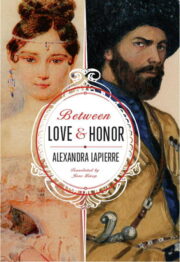

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.