Exasperated by his weakness, he turned his attention to his grandmother, who had come to his bedside. The ordeals of the past few years and the anxieties of recent months had made her thinner and broken her frail figure. Even Jamal Eddin realized that she was now a very old woman. He knew as well that her dignity, her will to live, and a desire to fulfill her duty were what kept her going. She still carried her head high and looked straight ahead; nothing diminished the liveliness in her eyes or the gentleness of her smile. Bahou-Messadou went about her business with her usual energy, coming and going from sickroom to kitchen, from well to fields, receiving the guests her age and rank attracted here in the new capital, for the time being in her grandson’s room.

All Jamal Eddin saw was the look that she gave her guests, her gray eyes shining and attentive above her veil as she listened to their requests. He could tell that she was not smiling; on the contrary, she grew more serious and sober. What news had they brought her that was so grave?

They were poor and dirty. Their cartridge belts and the sheaths of their sabers and kinjals were plain, enhanced by no silver. What did they want? Jamal Eddin heard only a breathless murmur.

Only the customary compliments praising the khanum Bahou-Messadou’s wisdom, spoken loudly in Arabic, had been intelligible. They had heard of the goodness of Shamil’s mother, they said, and of her son’s respect for her, as far off as their little village. This had given them hope she might understand the horror of their situation.

Their command of Kumik being limited, they spoke in Chechen. Jamal Eddin understood only one word out of two. Each of the three men said more or less the same thing, and little by little he grasped the situation. At home, the hardships of war had become close to unbearable. Since the grand padishah’s tour of the region, the infidels had returned with a vengeance. Three times they had burned the village to the ground, raping their women and taking their children as slaves. They had followed the imam’s orders. No one had surrendered, and the men had managed to flee to the forest. Three times they had rebuilt their villages from the ruins. Three times the Russians had contaminated their wells, burned their harvests, polluted their mosques with filth, killed their sheep and goats—everything. The village had resisted, three times. Following Shamil’s law, no one had surrendered.

But even the most courageous could not face the famine that was sure to come with winter. Dysentery had done the rest, and with the summer, the Russians would return. The only ones left to fight them were the sick and the wounded, a few old men and some women. The village needed some relief. The village must make peace with the infidels, even for just a few weeks, a few months. But how could they make peace? The murids were everywhere, punishing even the thought of surrender. Between their cruelty and the czar’s, between mutilation and hunger, there was no choice—and no hope of survival. Could the khanum talk to the imam, tell him personally of their situation? Ask his consent for a temporary capitulation, allow them to lay down their arms for just a few days? The time to take a deep breath?

“This will be difficult. Very difficult.”

The child stopped listening. He turned his face toward the door, dreaming of the moment he would jump on Koura the Proud, gallop through the three gates of the enclave, and ride off down the mountain.

After she had fed and bandaged her grandson for the evening, Bahou sent a servant to Shamil asking permission for a visit. She waited in her own apartment in the harem instead of Jamal Eddin’s room. The invitation came at a bad time; Shamil, his naïbs, and Yunus were deep in consultation. Bent over a map of Chechnya, Shamil listed the communities that were ready to betray him. It was unusual for his mother to disturb him at this hour. Surprised, almost apprehensive, he interrupted the session and went immediately to her home.

Witnesses said later that the imam stayed for a long while, leaving Bahou-Messadou’s apartments only at about midnight.

He left the harem with heavy steps, walking along the gallery past his son’s room without even looking in. He strode into the room where his counselors were still waiting for him, walked past them, crossed the courtyard, entered the mosque, and shut the door.

Alone.

It was broad daylight when Jamal Eddin woke up. The door to his room was wide open, and the slate gray light of a storm hung over the gallery, the courtyard, and the ramparts. There was no sound at all, none of the ordinary noises of rocks being pounded to make powder, or the bawling of the buffalo when they were let out at dawn. No clamor of the newly arrived, forced to dismount before the walls of Akulgo because of the narrow alleyways. Even the muezzin was silent, and there was no call to prayer. Fatima, Jawarat, and Patimat were nowhere to be seen. He could not hear Mohammed Ghazi and Saïd, Jawarat’s son, playing in the courtyard of the seraglio. Yunus’s three children and Sheik Jamaluddin’s were not crying. There was no noise, no movement, not a breath of air, not a sign of life. Absolute silence had fallen on the house, and the city. Only Muessa, Shamil’s cat, locked in his master’s house, meowed pitifully, his cries filling the emptiness. No servant came to feed him or set him free.

Jamal Eddin wiggled, trying to sit up, trying to understand. His arm hurt, but his concern was of another nature. Where was Bahou? What had she told the men yesterday?

“I’ll try.” That was all. “I’ll try. It will be difficult, very difficult. But I’ll try.”

He remembered that the Chechens had thanked her profusely, and that she had discouraged their thanks.

“I can’t promise you anything. Come back tomorrow after the second prayer.”

That was all. Was it really all? Jamal Eddin searched his thoughts.

“I’ll try.”

And since then, she had disappeared.

He stayed there, tied up, all morning long.

Around noon, the three Chechens returned to the room just as Bahou arrived. With an anxious look, she nervously pulled her veil down over her forehead.

“The imam cannot give you his authorization,” she muttered. “The imam cannot decide, it is Allah who commands. My son is at the mosque, praying, fasting, and listening to the voice of God.”

Avoiding the light and muttering unintelligible comments, she returned to the corner, where the Chechens had left her the day before.

“Shamil orders the people of Akulgo to join him,” she said rapidly, continuing in the same breath, “wait there, wait with him, pray, repent, and wait for the will of Allah.”

She added a few confused words and fell silent.

The three Chechens left hurriedly. Jamal Eddin heard Yunus stop them at the end of the gallery. What were they doing in Shamil’s house? Who had invited them?

Bahou-Messadou answered no questions. She was praying.

Outside, the morning silence had changed to a dull grumble, announcing the coming storm.

Blind and deaf to the world, she rocked back and forth, reciting her prayers softly. But Bahou’s chanting did not rise to God in his heaven, and it brought her no peace. What premonitions, what signs, what omens did she sense? What had she asked Shamil yesterday, and what business of hers was it? What had she said, and what had she done?

His heart going out to her, Jamal Eddin watched her shrink from one hour to the next, becoming a little old woman who moaned and droned just like other little old women. The child felt her anguish.

All day long, she did not move from the shadow at the back of the room. No one came to pay them any attention. It was as though neither one of them existed.

“Come to me,” he begged. “Bahou-Messadou, do you hear me? Come, set me free.”

By dusk, he no longer begged but snarled like a wolf, “Come here.”

She hesitated then. Humble and unsteady on her feet, she rose.

“Closer!” he insisted.

“Take your kinjal and cut my bonds,” he ordered.

The brutality of his tone made her conscious of her surroundings.

“Cut them!”

She obeyed.

What was left of his grandmother’s dignity now? She set about awkwardly changing his bandages in a disordered fashion, like a servant.

When she had taken them off, a pain shot through his arm, so sharp that he thought he would faint. But what was his suffering in comparison to Bahou-Messadou’s terror?

He clenched his teeth harder, stood up, and took her by the elbow, leading her out the door.

The house was empty.

The waves of people streaming through the alleyways carried the boy and his grandmother along toward the mosque. A huge crowd had gathered before the flat-roofed building to which the imam had retreated in solitude. The men had spread their prayer rugs on the square. The women stood, arms reaching toward the sky, uttering prayers and moaning softly.

The crowd fell silent as the khanum appeared, bent over beneath her veils. The tide of faithful parted before the old woman and the child.

It was a low-built mosque, with neither a minaret nor a dome. Funeral ceremonies were held upon the terracelike roof. The muezzin issued his call to prayer from an overhanging wooden ledge, supported by solid pillars. Jamal Eddin tried to lead Bahou beneath this little balcony, which served as an awning of sorts for the building. The slightest brush against his arm revived the pain and struck him to the quick. Pale as guilt-stricken criminals, the pair made their way through the mass of people to the closed door.

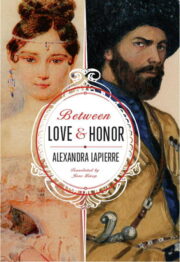

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.