Fatima, Jawarat, Patimat, the wives of the naïbs, and the professional mourners knelt in the dust in a row directly before the door. All begged for pardon, sobbing and lamenting their faults.

Bahou knelt just before the doors, between her daughter and her daughters-in-law. The moaning that had ceased at her passage began anew, more loudly this time. Mohammed Ghazi, the children, and the babies added their tears to those of their mothers. Jamal Eddin remained beside them.

For two days and two nights, the murmur of groan and supplication carried on unceasingly. The crowd camped on the square, praying and fasting among the horses, cows, and goats. No one dared leave. Everyone waited, and their prayers filled the blank skies of Akulgo with a menacing rumble.

On the third morning, the sudden creak of the hinges signaled the opening of the double doors. The crowd fell still as Shamil appeared upon the threshold, arms open.

Blinded by the light of day, his livid countenance framed by the stray whiskers of his bushy red beard, he stood still for a long moment before the prostrate crowd.

Supported by Yunus and Akbirdil, Bahou-Messadou dragged herself toward him. She kissed the ground and knelt there at his feet, her forehead touching the dust. The imam’s eyes were swollen, as though he had been weeping. He studied her in silence. Then he climbed the few steps up the ladder to the terrace, which was scarcely higher than he was.

On the roof, Shamil raised his right hand and turned his eyes to the south.

“Oh, Mohammed, thy will be done, thy judgment fulfilled,” he proclaimed. “Would that thy just sentence serve as an example to all true believers. For thy commandments are unchanging and sacred!”

He turned to face the crowd.

“Murids of Akulgo, hear now the message of the prophet.”

Jamal Eddin had never seen that look, nor heard that voice. Normally he loved nothing more than Shamil’s eloquence. His father’s passion, the fervor of his fearsome harangues, which inspired in him a love of God and the ardor to serve Him, normally filled him with delight.

But his father’s tone today was utterly foreign to him.

“The Chechen people, forgetting their vow, are ready to submit to the will of the Russians and obey their laws. Their emissaries, too craven to tell me of their dishonorable proposals, addressed themselves to my mother. Playing upon her great kindness and her weakness as a woman, they convinced her to appeal to me in their stead. Her insistence in pleading their cause, her tears for them, and my infinite love and respect for her gave me the strength and the boldness to seek the will of Allah through Mohammed. With the strength of your devotion and your prayers to sustain me, I have thus begged the favor of the prophet, that he should deign to hear my presumptuous question. This morning, after three days of fasting and prayers, Mohammed gave me a response. And I was stricken by the thunder of His voice.”

The crowd held its breath. Shamil drew himself up to his full height.

“Allah has ordained that the person who first spoke to me of submission should be punished with a hundred lashes. And the first one who spoke, that first person, is my mother!”

Bahou-Messadou uttered a cry. A moan rose from the people. Jamal Eddin felt himself trembling. He searched his father’s eyes, but Shamil’s stare was fixed and veiled. Yunus and Akbirdil, holding up the old woman, bowed before him in silent supplication. Everyone knew that a Muslim was not permitted to strike his parents. All were aware that Shamil worshipped his mother. And they knew that a hundred lashes meant death. Surely the imam would commute the sentence.

“Bring her up here and tie her up.”

At his words, the mourners broke into a strident clamor of ritual keening, the lamentation of a funeral ceremony. They followed the executioner as he dragged Bahou-Messadou up the ladder.

Jamal Eddin wanted to scramble in front of his mother, Patimat, the naïbs, all of them. Whereas before he had been trembling, now he was shaking violently.

He was the last one on the roof. The executioner had already tied Bahou-Messadou’s arms behind her back. She was weeping.

Jamal Eddin saw the executioner hesitate. How could he dare to rip the tunic and reveal the flesh of the imam’s mother? The crowd felt a surge of relief and hope.

Shamil was already snatching the whip from the executioner. He was going to commute the sentence. Jamal Eddin took heart. Shamil would grant her mercy.

And then he saw his father rip Bahou’s tunic, raise his arm high, and strike her himself with all his strength. She howled in pain. Before the child’s horrified eyes, the whip stung her back and slashed at her shoulders and sides. He watched the leather strips tear into her bony back. Two blows. Three. Bahou’s cries became weaker.

By the fifth blow, Bahou-Messadou was silent. She had fainted.

Jamal Eddin saw his father throw himself upon her and untie her. What else would he subject her to, what further torture and torment? As he watched, his father fell, weeping, to his knees upon the prostrate figure.

Shamil’s tears, the tears of his father, filled him with terror. Jamal Eddin had never seen a man cry. He suddenly sensed Shamil’s unspeakable despair.

And Shamil’s despair was that of God.

But the imam was already on his feet. He turned his burning gaze to his son, his wife, his naïbs, to all of them.

“There is no other god but Allah, and Mohammed is his prophet!”

Towering over the people of Akulgo, he raised his face again to the sky.

“Oh you, who dwell in paradise, you the blessed and the chosen who rejoice in the eternal beatitude of the gardens of Allah, you have heard my prayer! You allow me to submit to the rest of the punishment to which my poor mother has been condemned. I accept these blows with joy, they are the gift of your love and your infinite mercy!”

He unbuttoned his cherkeska, took off his shirt, and knelt beside his mother’s still body.

“Executioner,” he ordered, “give me the ninety-five lashes yet to come.”

The executioner still hesitated. How could one whip the imam?

“Disobey the will of Mohammed and I will kill you with my own hands! Strike me!”

The lash descended.

Jamal Eddin could no longer control his face, his body, his soul. Everything within him had turned wobbly and unsteady. He tried to pull himself together, counting the lashes with the executioner. But he heard the crack of the whip and its slashing descent from somewhere far away. Whistling through the air, it took his breath away, and he felt it burn to his very marrow.

The leather strips dug into his father’s shoulders. The lacerated flesh fell away, its scarified layers swelling like the leaves of a book consumed by flames.

By the ninety-fifth lash, Shamil’s back was nothing but a black, shredded mass, a magma of muscle, flesh, and blood. He rose slowly, picked up his tunic, and covered his wounds.

And then, he turned again to his people, who knelt before him.

“Where are the cowards?”

He leapt from the roof in a single bound.

He scrutinized the crowd of faces frozen in terror.

“Where are the traitors?”

Striding through their ranks, he stopped before each bowed head and repeated, “Where are the hypocrites who brought this punishment upon my mother?”

Yunus and Akbirdil dragged the three Chechens forward and threw them at his feet. They scrabbled in the dust, their faces to the ground. None of them offered excuses or explanations or thought to beg for mercy. The best they could hope for was that the end might come quickly. They murmured their prayers.

Everyone waited for Shamil’s verdict. He leaned toward the three men preparing themselves for death. The executioner drew his saber and waited expectantly.

Standing on the roof above their heads, a petrified Jamal Eddin closed his eyes.

If only. To see nothing, hear nothing. Disappear with them.

“Take courage…”

Shamil made the Chechens stand.

“Return to your village and tell your people what you have heard at Akulgo. Tell everyone at home, in your auls and your forests, of the word and the will of God. Spread the word everywhere, of what you have seen here. May Allah be with you always. Go in peace.”

For the child, this spectacular pardon, this mercy that defied all the traditional codes, all the laws of Shamil, was the ultimate upheaval.

He swayed on his feet and vomited.

After the guilty men had set out again upon the mountain path, blessing the imam for his wisdom and mercy, Shamil returned to his mother’s side. Leaning over her, he took her in his arms with infinite tenderness and carried her home, still unconscious.

His demonstration before his people had cost him dearly.

Like all who had witnessed the drama, Jamal Eddin understood the lesson. By ordering his servant to strike his own mother—when the authority of the elders was sacred and inviolable—the imam had offered proof of the boundless wrath of Allah before the Chechens’ weakness. As clear as it was effective, the message spread throughout the Caucasus. Of all sins, peace with the infidel was the fault that Allah could not pardon, the crime He would punish most harshly.

No one, ever again, should pronounce the words of damnation. No one, ever again, should speak of surrendering to the Russians.

In the depths of his being, Jamal Eddin absorbed the obvious message: Shamil lived in union with God. Jamal Eddin’s own destiny was to live and to die for Shamil. And yet he discovered that, contrary to all his experience, in contradiction of all appearances and his own convictions, his father was not omnipotent. A power infinitely superior to Shamil’s will dictated his conduct, constrained him, and tormented him as He tormented all men. It was then that a profound mistrust of this mysterious force that was stronger than his father was born in Jamal Eddin, a wariness that knew no bounds. The boy was not afraid of the Russians. He had never been afraid of them. But the wrath of God that had commanded his father to beat Bahou-Messadou filled him with terror. It took root in the heart of the child, as it had once grown in the soul of the old woman.

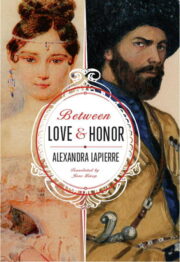

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.