This disagreement with the last of his forebears troubled Shamil.

“Nothing is written in the book of destiny that Allah has not decided,” he said with restraint. “We must play for time and wait for Chechen reinforcements to come.”

“But the Chechens are blocked on the plain, by that dog of a Klugenau that you spared!”

The memory of this missed opportunity caused a rumble of discontent and more than one bitter remark. They should have slit his throat, against Shamil’s will, they should have slit that pig’s throat at Chirquata. It would have been so easy.

“Once, you were willing to talk to the Russians, Imam. Let us open negotiations.”

“That’s useless. They will not give us peace and freedom.”

“If you don’t negotiate with them now, when they want to talk too, they will kill all our men, dishonor our women, and turn our children into slaves.”

“If we negotiate with them now, they will bring every Caucasian Muslim to his knees, you said so yourself, Barti Khan. They’ll make all of us, you and him and me, their serfs. They will throw the servants of God in the dust and keep them bent under their yoke. I’d rather kill my three sons, slit their throats with my own hand, down to the very last, than let them live in slavery. Purify yourselves. Burn the spirit of servitude that has shackled you from your souls.”

He leaped to his feet and stared down at them all.

“He who serves Allah cannot serve the Russians at the same time,” he said severely. “Will you renounce the promises of heaven for these dogs? Here, our hours are measured by the day. But up there, our lives will be eternal. Our native land is in paradise, and each of us has a home prepared for him there. But listening to your words, I’m sure none of them will be inhabited!”

He turned on his heel and left the grotto abruptly.

The waning moon had swept away the cloud of heat. Shamil felt so tired, so fatigued and so alone that the trials of this world left him close to despair. Was he mistaken? Had God ordered him to make peace? Should he dispatch an intermediary to the camp below? Should he send Yunus to negotiate in his name?

His sorrow mingling with envy, Shamil thought of his dead friends who had already entered the Gardens of Allah. Water as pure as diamonds flowed from the fountains where they had all of eternity to slake their thirst and rest in the shade of the cypress trees. Beautiful virgins with shining eyes and arms as round as swans’ necks waited for them in their homes. And he was here, watching the birds of prey hop between the stones to peck at the cadavers of his people. Was it he, Shamil, the shadow of God on earth? Or these black birds that hovered like a cloud over Akulgo that Jamal Eddin chased with stones?

The child had not left his side for nearly a week. He followed him everywhere, walking a few steps behind, alert to his every need, aware of his doubt and dismay. The boy relieved him of his weapons, took his messages to other survivors in the grottos, and cared for his horse when he returned from combat. Shamil let him do all this without a look, without a word, accepting his presence as a gift from God. This evening, for the first time, he looked at the rags hanging from the boy’s emaciated frame. The oval of the small face was so thin that it seemed to have changed shape, and the high cheekbones and once almond-shaped eyes had turned to slits beneath his puffy eyelids. He noted the boy’s fixed stare, the long lashes no longer able to hide his feverish look. His son, his disciple, his comfort.

The stifling night weighed upon his shoulders.

Continue the war and perish tomorrow? Capitulate tomorrow and save the children of Akulgo? He could find no answer within himself. Had Allah abandoned him? What did he ordain? Shamil no longer heard the voice of God.

He walked down across the roofs to the entrance of the village, passing slowly from terrace to terrace, striding across the interstices of the narrow alleyways, avoiding the holes in the structures. He walked from one end of New Akulgo to the other, all the way to the terrace of his former fort. He walked up the ruined crenels and sat down on the parapet overlooking the chasm. Jamal Eddin sat down on his lap, one leg dangling over the abyss. There they sat, immobile, as exposed to enemy fire as possible. From down below, they must be all the Russians could see, the imam with his white turban gleaming in the moonlight and the bare-headed boy. Why were they waiting to shoot? From here or in the back if they liked, from the distant tower above.

Unconscious of or indifferent to danger, Jamal Eddin leaned back slightly against his father’s chest. Shamil put his arms around him and held him as he had once held him long ago, when he had whisked him away from the battlefield, seating him on his horse’s withers. Jamal Eddin snuggled up to his father’s breast, feeling his warmth and his strength. Eyes half-closed, he looked at the river, the rows of white tents, and the chain of mountains rising unevenly beyond the Russian camp. The blue mountains of the Caucasus, their mountains. He closed his eyes, still seeing the image of the mountains, distinct and luminous, in his mind’s eye. He felt his father praying, reaching toward God, and he let himself go, sinking back against him.

“O Lord,” Shamil murmured, “this child is the soul most precious to me on this earth. If you take me with a bullet in the forehead, do the same for my child.”

Jamal Eddin was still. He knew that, at this instant, his father was testing the will of the Almighty.

Did Allah want them both to die?

“Allah be with you.”

“The Lord be with you.”

“General Grabbe replied to our overtures,” Yunus said as he bent over to slip into the grotto where the council was meeting.

He carried a piece of paper in his hand.

“What kind of a Russian is he,” Shamil growled with disdain, “this Pavel Khristoforovitch Grabbe?”

“What can one say about a chief who doesn’t take part in combat? A coward.”

“And what else?”

“An enemy without honor. He lies like all the others.”

Shamil slowly breathed in the hot, muggy air, as though to absorb all this. His lieutenants had forced him to compromise, to feign a desire for peace in order to gain time and put off the final attack. They would simulate an overture for discussions, act as though they were debating the possibilities, and drag out the negotiations.

Until the Chechens got there.

“Four propositions.”

“I’m listening.”

“All of them unacceptable,” Yunus added calmly.

“Read aloud, so everyone can hear.”

“First, the imam will offer his son as a hostage, an amanat.”

Jamal Eddin could not help but start. Shamil was impassive.

“Go on.”

“Second, the imam and all the inhabitants of Akulgo will give up their arms to the officers before leaving the village and coming to surrender. They and their families will be safe, under house arrest in a location that General Grabbe reserves the right to choose. The rest—”

Shamil motioned for him to stop there.

“The rest we know. The massacre of the elders they disarmed at Ghimri, the disappearance of my nephew, taken as an amanat at Tiliq.”

“The rest,” Yunus continued to read, “is up to the magnanimity of the czar.”

“Send them an emissary with other propositions,” Barti Khan suggested.

This time, Yunus was not received. General Grabbe was waiting for new cannons. He too knew how to be crafty, to drag things out, to “negotiate oriental style,” he said.

He needed no reports from his spies, imagining with little effort the horror of the situation on the piton. The smell was enough. Even down here in the camp, the stench was such that the poor sentinels passed out on the riverbank, handkerchiefs to their noses. They had to be relayed every half hour. His soldiers, either conscripted peasants or serfs of the empire, had seen as much in Russia, yet nothing compared to the vile odor of Akulgo.

The general stalled, on the pretext that he would not open talks until the imam sent his son.

“Never will I give Jamal Eddin to the Russians.”

“You’re going to let all your people be massacred, just to spare your son?” Akbirdil said, astonished.

Hadn’t he sacrificed his own firstborn, Hamzat, without a word of hesitation? And the others, the eight naïbs present, hadn’t they sacrificed their own children?

“Your thinking is off, Imam, your judgment colored, and how can it be otherwise?” Barti Khan suggested. “You are both judge and defendant in this affair.”

The moment the rumor of peace spread, Fatima sensed danger. The infidels always demanded hostages in their talks with the Montagnards. People said they let their amanats starve to death in their forts, that they poisoned them.

She could not share the imam’s bed, for she was pregnant. She couldn’t even touch him, approach him, speak to him, or listen to him. But she did not let him out of her sight. When Shamil left the council den, when he went off by himself to pray or prepare for battle, he found her there, in her veils, kneeling in his pathway. Her eyes looked up into his in a silent appeal. With all her heart, the beloved begged for grace for their son.

Shamil fled from her presence.

Sitting on a rock at the entrance to the family grotto, Jamal Eddin felt vaguely bothered by the looks people gave him. In no way did he seize their significance. Picking lice off him, Patimat peered at him as though she were seeing him for the last time. She said nothing. She did not scold him. She just kept fussing over him, taking advantage of the calm to hunt the lice and shave his head meticulously. Her dedication to her task was scarcely typical.

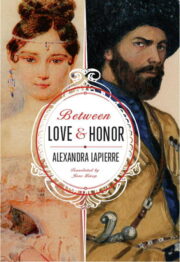

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.