Indeed, Sacha was in fine form tonight. Everything was turning out for the best.

Dmitri was thinking the same thing as he sat down in the banquet room. Everything was turning out for the best.

Only the adults, the young people between sixteen and twenty, and the adolescents of the imperial family had been placed at the table. The rest of the children were seated at the two extremities of the horseshoe, the boys with their tutors, the girls with their teachers.

Due to the random order of the procession through the reception suite—the random order, or the skill of Buxhöwden, who had been confidentially informed of the potential difficulties of the evening—Sacha, his friends, and the sons of some of the guests entered the dining room last. Count Kiselyev already presided at the center table, with the two grand dukes, the princes of the Bagration family, and the generals seated next to him. Countess Kiselyev, née Princess Potocka, was seated at the center of the right wing, with the Georgian princesses and the other ladies across from her. Dmitri presided over the left wing of the table, surrounded by the dignitaries and officers. On the men’s side, the table was nearly full, so the dozen or so last to arrive sat on the other side, with the readers, chaperones, and governesses.

Dmitri sat back in his chair, satisfied with the arrangements. Yes, it had worked out fine to leave things to chance; in fact, it could not have been better if it had all been planned. Sacha’s band was directly in his line of vision, so he could easily keep an eye on Jamal Eddin. Even better, the group of chaperones separated the boys from the rest of the guests. It would be impossible for “the rebel,” as his uncle insisted on calling him, to hear any conversation other than that of his friends. No one had noticed the boy during the greetings and the procession. He had blended into the mass of uniforms. And no one would single him out now, seated on the other side of the world, two hundred place settings away from General Grabbe. The problems he had foreseen had simply disappeared.

One could even suppose that the boy would do his best not to attract attention. Wasn’t this reception his first, his introduction to society? His first formal dinner, his first ball? Dmitri recalled his own state of mind in the same circumstances. He had been fourteen and in mortal fear of appearing ridiculous, gauche, or awkward. His most fervent wish had been that no one should look at him or notice his presence.

And as he watched him, Jamal Eddin did not say a word. With his usual reserve, he seemed to want to disappear, sitting back slightly in his chair so that his neighbors could fully observe Sacha’s antics.

Sacha, on the other hand, was too much. He was going too far with his clowning. Dmitri knew that his little brother was trying to impress his rivals—in fact, all the boys at the party—because he thought he was ugly. Or at least he did not think he was as handsome as Their Imperial Highnesses who, with their blond hair and blue eyes, looked more German than Russian. They were the incarnation of all he wanted to be. But they were seated too far away for him to compete with them. Buxhöwden? Sacha definitely considered himself to be less masculine than Buxhöwden, who was a strapping, well-built, somewhat enigmatic lad. Jamal Eddin? Sacha undoubtedly knew that he was less attractive than Jamal Eddin, with his high cheekbones and large, almond-shaped cat eyes. Well, the devil with looks. With his turned-up nose and freckles, and the cowlicks he was forever trying to paste down, he was determined to be as witty as could be. So he exaggerated his comic side, overcoming his shyness by speaking loudly and gesticulating wildly.

Dmitri saw him address the two girls he had greeted in the vestibule, speaking over their governess’s head. They laughed unrestrainedly at his clever comments.

They were the younger sisters of the beautiful young woman sitting next to her mother at Countess Kiselyev’s right. Dmitri thought, deep down, that had he not been so happily married, the lovely Princess Anna of Georgia… In any case, Sacha’s conquests were named Varenka and Gayana. Varenka was fourteen, Gayana a year younger. Endowed with a delicate constitution, Varenka was slender and frail, with immense dark eyes and well-shaped, arched eyebrows. Gayana was a brunette like her sisters, but chubbier and livelier, and every bit as impudent as Sacha.

Placed on either side of their teachers, the girls wheedled their two chaperones into exchanging places with them, allowing them to sit next to the boys. They had just won their case and were sitting down between Jamal Eddin and another boy, who wore the prestigious gold-buttoned blue uniform of the Lycée Impérial, where Pushkin had studied. A smile crossed Dmitri’s lips. They were having a much better time at their end of the table than he was here, in the company of the minister of war.

Finally reassured, he ceased to pay attention to the goings-on around his little brother. The game had been won.

However, on this score, he was mistaken. The student from the Lycée Impérial, who was talking even more loudly than Sacha, was making him dangerously excited. As for Jamal Eddin, he was struggling to control a violence well beyond what Dmitri could have imagined a short while ago when he tried to put himself in the boy’s place.

What was so oppressive? The solemnity of the décor, the heaviness of the twenty-four white pillars, the Corinthian columns that supported the enormous vault above? What was it? The light? The heat? The shimmering flames reflecting off the crystal of the chandeliers and dancing in the mirrors like fragments of a rainbow? Whatever it was, Jamal Eddin felt trapped, caught by the throat, close to panic.

Tonight he was capable of measuring what had escaped him five years ago during the New Year celebrations at the Winter Palace. He could judge the splendor of all these objects, let himself be dazzled by the refinement of each detail and fascinated by so much richness and radiance.

He knew both too much and not enough about the world around him.

Though he had learned how to navigate in the realm of the cadets, he suddenly understood the great distance he still had to go. Yes, of course, he knew how to recognize an officer’s rank at a glance and how to salute according to protocol. His table manners were impeccable. But for the rest? His masters had not shown him how to click his heels before a girl or revealed how to flirt with her. And when it came to mastering the correct dinner utensils before him, all these knives and glasses, he was at a loss. Dmitri had been right in supposing that Jamal Eddin felt awkward and ashamed. But added to his adolescent emotions was another kind of malaise, a moral one that multiplied and complicated his discomfort.

He didn’t even need to touch the wine that sparkled red, white, and golden before him, the wine his father had poured out by the cask—the odor was enough to inebriate him and fill him with guilt.

In coming so close to what he never should have approached, in discovering the opulent beauty of women he should never even have imagined, in running his eyes over their plunging décolletés and their bare shoulders, he was playing a dangerous game with temptation. And he sensed this.

He wished he had never accepted Sacha’s invitation. He was angry with himself for taking part in it. He was angry with himself for being at this table, in this room, in this palace, in this country. He was angry with himself for everything.

He looked for an opportunity to disappear discreetly, but it was too late.

“Jamal Eddin,” Sacha cried, “you who know the region, the Caucasus belongs to Georgia, right? So Her Highness the Princess Varenka Ilyinitchna and Her Highness the Princess Gayana Ilyinitchna are at once Russian, Georgian, and Caucasian, no?”

Given his present state, Jamal Eddin did not understand the question at all.

“Monsieur maintains that that’s not the case,” Sacha insisted, indicating the student seated across the table from him. “Monsieur declares that Orthodox Georgia and the Muslim Caucasus have nothing in common.”

“I never said that!” the boy cried.

His voice was changing. Sharp and shrill, it carried a long way.

“Oh, really? Then what did you say?”

“I said that only part of the Caucasus Mountains are in Georgia. And that in this sense, the Georgian people are more Russian than Caucasian.”

The sententious student liked giving lessons.

“That’s totally idiotic!” Sacha burst out, ready to say anything in order to have the last word.

“All of the Caucasus is Russian,” said his adversary, developing his rationale.

“All the Caucasus is not Russian,” Varenka corrected him.

This intervention put a damper on the heated conversation, and a moment of silence ensued. Buxhöwden squirmed in his chair, sensing the danger. Jamal Eddin did not move. He listened intently to the girl’s words.

“The proof,” Gayana simpered, “is that Varenka’s sweetheart was Shamil’s prisoner for eight months in the Caucasus.”

“He’s not my sweetheart!”

“Maybe. But anyway, he was Shamil’s hostage for eight months.”

“Shamil?” smirked Sacha’s rival. “My father had him under his boot.”

The color drained from Jamal Eddin’s face. He was so visibly upset that Buxhöwden was afraid he would completely lose his composure.

“Our relative, Varenka’s fiancé, lived with him in his village, in his house,” Gayana professed insistently. “He says that Shamil is not at all the way everyone imagines him. He says that he is a great warrior, and he admires him.”

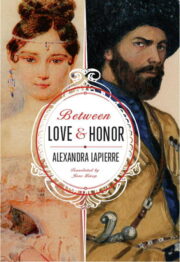

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.