“But he belongs to our world now. He is part of us.”

“You’re right, but then again, you’re wrong. I want him to be both Russian and Cherkess. Completely Russian and just a little Cherkess—that’s what I’m aiming for with this boy.”

“I can’t imagine him any other place,” she persisted, “or any other way. What if he falls in love one day? What if he should want to marry, to start a family?”

“Mouffy, whatever are you talking about? He’s only sixteen.”

“And you were only twenty when you married me.”

“What does one have to do with the other?”

“What would happen if he were taken with a young girl in our entourage? In his entourage, I should say. One of the maids of honor, for example? Like Constantine, like Nicky, like Mischa, and all their friends, like every one of you here.”

By alluding to the czar’s conduct, Alexandra Feodorovna was venturing out on shaky ground. Three years ago, when their daughter had died, he had taken a mistress, one of the maids of honor at the palace. He had fallen in love with her and pursued her mercilessly, and she had finally consented.

The empress had accepted this liaison, just as she accepted everything about him.

Her many pregnancies and the exhausting pace that the emperor demanded of her when they were not at the cottage had taken their toll upon her health. She had already suffered several cardiac alerts. The doctors, fearing that the next one would be fatal, had forbidden her from indulging in her conjugal duties. Nicks, full of energy and in constant need of activity, had no choice but to form other ties, elsewhere. She forgave him.

The emperor of Russia was so good, so just. So perfect.

Nonetheless, her jealousy was palpable. The proximity of the young woman, whom the czar had installed in a pavilion in the park and whom he insisted be present at every meal, caused the empress unbearable suffering.

In a sense, her marked preference for other young women, for Anna, for all the youngsters of the Georgian family who would serve her one day, was a means of distancing the czar’s chosen one from her own intimate circle.

“I understand Jamal Eddin has a penchant for one of the princesses,” she continued.

“What normal, healthy young man wouldn’t have a weakness for Anna? I’m glad he knows enough to appreciate all the beauty around us, Mouffy. The beauty that you yourself incarnate.”

“So do they,” said the empress pensively, nodding toward Varenka and Gayana, who stood among the hydrangea blooms. “So do they, Nicks, they are beautiful.”

Alexandra Feodorovna hurried down the slope to greet her guests.

The curtains fluttered, white and diaphanous, and floral scents from the garden floated in with the breeze. Light streamed into the dining room. Jamal Eddin loved nothing more than these meals with the entire family gathered around the long table. He loved the sonorous voice of the czar commenting on military reviews and the empress’s soft, melodious inflections. He anticipated the rustle of Anna’s petticoats before she even appeared. He loved her sparkle and how passionate she was when she spoke of the Georgia of her forbears. He even liked Nicky’s asides when he leaned close to Jamal’s ear to point out the young girl’s charms. He loved the delicate clarity of the glass in the bay windows and the streaks of sunlight on the pastel-painted walls, the warmth of the parquets and the shouts of the imperial grandchildren—Grand Duchess Maria’s four sons and the czarevitch’s two—as they played at his feet. Everything felt so familiar to him now.

And now, this miracle, the long-dreamed-of appearance of Varenka. His friendship with her sister and their bond of complicity within the circle of the imperial family had strengthened the tie and kept his memory of her alive.

Every night since he had met Varenka at Sacha Milyutin’s, he had relived that moment in the Hercules Rotunda, that face, as he drifted off to sleep. Varenka’s presence made this new day at the cottage perfect. Dazzling.

Calm down, Jamal Eddin told himself. Control the turmoil inside for a moment. Stop and think. Varenka was here. And he was going mad.

Sitting on the bench in the shadow of the sculpted bust, he breathed deeply.

At the cottage, an impromptu ball was about to begin, a country dance on the lawn in honor of the visitors. And he was possessed by a desire to join the festivities, perhaps even dance with her.

Get a hold of yourself.

A rumble of unusual activity from the Peterhof Palace nearby signaled that the carriages were coming for the guests. A line of teams clip-clopped down the lanes leading to Alexandria, and he could make out lights beyond the trees. In the glade behind the house, he knew they were setting up a buffet and stringing Chinese lanterns between the trees. But he would respect his spiritual meeting with Shamil. He would force himself to stay seated in this quiet place longer this evening than on other evenings after prayers.

Excited bats traced endless circles above the green outdoor room. Though he could find nothing to say to his father, he refused to give in to his own impatience. He would stay here in his company for as long as it took him to regain control of himself.

“What do young people dream of on a moonless night like this?”

The emperor’s voice.

Jamal Eddin started.

“Don’t get up. I’m pleased that this place is still alive, that of all the benches in the garden, you have chosen this one.”

Instantly recognizable, the czar’s deep voice conveyed its usual authority but lacked its usual composure. He hesitated.

“This is where my daughter loved to come.”

Jamal Eddin was embarrassed by his own ignorance and lack of tact as he suddenly understood: the bust of the young beauty between the benches was a memorial to the dead girl. How could he ask forgiveness for sitting in so sacred a place? He stood up, immobile before the powerful mass of a man who sat down in his place. The shadows were so deep that he could not make out the czar’s features, not even the shape of his face.

“She used to read here, she—”

His voice broke.

Jamal Eddin had known him only in strength and triumph. The sorrow of this capable and powerful man upset and intimidated him.

It was the same as long ago at Akulgo, when he had seen Shamil suffer, hesitate, then crumple in pain when he was to surrender his son. He would have liked to have relieved him of his burden, taken on his suffering on his behalf.

He wanted to express his love to the czar.

However, he dared not and said nothing.

“You never met her?”

Jamal Eddin shook his head. It was not entirely true; as a child, he had seen the grand duchess several times. He remembered her as a wonderful, distant vision. But he sensed that the emperor expected only the briefest of answers.

“Unfortunately, no, Your Imperial Majesty.”

“Alexandra. Her brothers called her Adini. Adini said that, from here—” The czar stopped, inundated by memories. “She said that the view from here—”

Overwhelmed by sadness, he could not go on.

Powerless and unhappy, Jamal Eddin stood still before him, the bust of the young woman barely brushing his shoulder. He was afraid to move and disturb the czar. For a long while, neither one of them spoke.

The emperor finally broke the silence, his voice full of sorrow and regret.

“She was an incomparable singer, such a musician. Of all my daughters she was the one who most resembled her mother. And she so loved—” He choked on his words, regained his composure, and repeated, “so loved life.”

At these words, the czar finally broke down.

It was then that Jamal Eddin made an incredible gesture. In a surge of sympathy, he knelt on one knee, clutching his benefactor’s hand in his own, and embraced him.

They clasped each other for a long moment.

The older man finally let go with a sigh, tapping him lightly on the shoulder.

“We are all in God’s hands. Our souls are not our own. He makes use of us according to His will.”

Finding consolation in this thought, the czar repeated, “I am the means he has chosen, that His will be done.

“And you?” he asked briskly, the tone and register of his voice changing abruptly. “What’s new with you? I’ve heard that the princess Potemkina is planning a big party in your honor at Gostilitsy?”

The warmth of his tone suggested that the news pleased him.

Disconcerted, Jamal Eddin did not know what to think or feel. At a loss for words, he rose to his feet.

The czar was well known for his mercurial changes, this manner of passing from one emotion to quite another in the same conversation, without any transition or warning. His interlocutors always found themselves baffled as he plunged them into another of a series of contradictory states. Some—the opponents he sent to Siberia—said Nicholas changed moods the way one would a mask; his contrasting expressions were merely the grimaces and poses of an unfeeling manipulator. Others—his loyal subjects—maintained that Czar Nicholas had such self-control that he prevailed in every situation, through his intelligence and moral strength.

“So, she has performed a new miracle, our good nun?” he exclaimed. “It’s true, she knows how to guide the most impenetrable souls to the path of love. I’m glad she succeeded in touching your heart, better than I, better than all of us.”

Jamal Eddin withdrew slightly. He stepped backward toward the bench.

“I respect the princess Potemkina’s faith, Your Imperial Majesty,” he said politely.

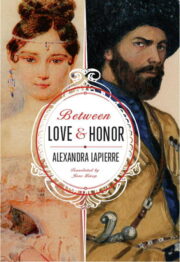

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.