“Live,” the emperor’s flute repeated to him joyously. “Live, Jamal Eddin!”

CHAPTER VIII

That Day May Dawn and Night Perish the Taste of Happiness 1848–1853

There was a roll of drums and a clash of cymbals. Jamal Eddin and his comrades stood impatiently behind the barriers at the edge of the field. The eleven brass bands of eleven regiments converged before them, saluting each other as they entered the parade ground. With each company playing its own theme, all eleven military marches burst into tune at the same time. While anyone else would have been stunned by the noise, the deafening racket lifted their spirits with pride and joy.

Today marked the justification and the apotheosis of eight long years of training.

Dressed in a white gown, the empress was enthroned in the first row of a sumptuous green box built for her at the edge of the field, surrounded by her daughter, daughters-in-law, ladies-in-waiting, and grandchildren. In the grandstands next to the imperial box on the same side of the field, the high society ladies flitted about, escorted by foreign officers, travelers, and visitors of rank rather than their husbands. The men of Saint Petersburg would serve in the arena. The highest dignitaries, Czarevitch Alexander, the grand dukes, and General Count Kiselyev, would lead their regiments in the parade. Even the cadets of the academies, who normally did not participate in military reviews at Krasnoye Sielo, would parade today. The special circumstances of this May 1848 justified the presence of the empire’s entire corps.

As a result of the revolution that had taken place in Paris the February before, Holy Russia had been forced to protect herself from the contagion of liberal ideas by preparing for war. Entertaining yet symbolic, today’s magnificent performance was a showcase designed to display the perfect training of the young recruits and the crushing power of the czar’s army. France, the constitutional republics of Europe, and other republics throughout the world were the intended audience. When the ambassadors left the grandstands shortly after the show, they would return home convinced that thousands of men stood as one behind God’s representative on earth. And that this amazingly cohesive and powerful bloc was the guarantor of universal order.

In the saddle since dawn, the cadets waited their turn. All of them searched the grandstands for the familiar faces of mothers, sisters, and their favorite girls. Like the others, Jamal Eddin scanned the crowd. There in the second row, gesticulating extravagantly, was La Potemkina, who loved the excitement of military parades and the odor of gunpowder. She was accompanied by her usual retinue, the patronesses of the prison committee and a gaggle of nieces and protégés. Most importantly, he noticed, the Georgian princesses were missing. The entire Georgian family was absent. Of course this was no surprise to him. This very month, Anna was to marry a Georgian prince of the illustrious Chavchavadze line of Kakhetia, and Varenka was part of the wedding party. He so yearned to parade before her, and up to the very last moment, he had held out some hope of seeing her. Fate had decided otherwise, and he accepted it, crestfallen. But even his disappointment could not entirely spoil his pleasure today.

The colors, smells, and sounds of war—the clarion of the bugles, the cannon fire, the pungent scent of leather and horse manure, the taste of gunpowder and dust—were intoxicating.

His eyes were riveted upon His Majesty’s guards as they crossed the field, parading in columns, as they had during the Napoleonic wars. He knew, as they all did, that each of these horsemen had been chosen because of his looks. Long legs, broad chests, splendid complexions, suitable eye color, and lustrous hair were the predominant criteria for joining this exclusive group.

The magnificent Preobrajensky Guards wore their famous green uniforms. All of them were exceptionally tall, like the czar. Broad-shouldered, regular-featured, slim-waisted, with sturdy calves, and mounted on identical chargers, they sought to evoke the reincarnation of the heroes of antiquity.

The green sea of Preobrajensky Guards gave way to the blue lines of the Semenovsky Regiment, followed by a white wave of Izmaïlovsky uniforms. The Pavlovsky Regiment, with their conical helmets and sabers drawn, a tradition fiercely won during the battles of the last century, brought up the rear. Then came the artillery, its first batteries of cannons on caissons drawn by teams of six bay horses. The second were drawn by sorrels, the third by gray barbs, and the last by black geldings.

The atamans of the Cossacks of the Don followed, riding little Kirgese mares. Then came the Uhlans, dressed in red-trimmed blue, a forest of lances broken occasionally by standards wrested from the Turks. Thousands of horsemen brought up the rear, and the cadets of the military academies closed the parade.

At the foot of the tribune, in the arena, the czar rode astride a prancing stallion, escorted simply by his brother, Grand Duke Mikhaïl Pavlovitch, and a bugler who trumpeted his orders. He directed the drills.

Jamal Eddin missed the gesture that silenced the crowd, but suddenly all eleven brass bands fell silent, and the thousands of horses came to a standstill, their riders waiting expectantly.

The grand duke galloped off to the edge of the field with the bugler. The czar remained alone, facing his troops. It was absolutely silent. Not so much as a neigh, the creak of a harness, the click of a bit, or the spin of a spur wheel broke the quiet. A powerful silence and stillness reigned over all, in the grandstands and on the field alike.

Then the czar gave a mighty cry, one word that echoed as far back as the ranks of the First Corps cadets:

“Charge!”

In one fluid movement, Jamal Eddin and his comrades, all the men, horses, cannons, and mounts, bounded forward.

Waves of green, blue, and white swept across the camp at lightning speed, the thunder of pounding hooves eclipsing the women’s cheers.

The czar stood stock-still before the tide of horsemen. His horse pawed the ground, startled by the approaching spectacle. Ten thousand horsemen charged toward the imperial box, headed straight for the emperor.

The distance shrank by the second, and it looked as though the mass would trample the stallion and the grandstands full of women. But the instant they reached the box, the ten thousand horsemen stopped as abruptly as they had started, as a single body.

The horses’ breasts formed a single line, their hooves aligned along an invisible mark that went on for several versts. Row after row, the ranks repeated their original order.

The only sounds were the bated gasps of the men and the snuffled panting of the horses. Their delicate nostrils quivered, some bleeding, less than a meter from the pale, distraught face of Czarina Alexandra and half that distance from the satisfied countenance of Czar Nicholas.

The sheer intoxication of participating in such a ballet, the excitement of executing such perfection, was inexpressible. Boot to boot, elbow to elbow, Jamal Eddin and his comrades—Sacha Milyutin, Buxhöwden, and all his comrades of the corps—had triumphed at this complex exercise, and their pride was boundless.

The feeling echoed Jamal Eddin’s long-ago memory of galloping among the murids, his brothers-in-arms. At the time, he had felt that he was part of the greatest army in the world, Shamil’s army.

More perhaps than all the other horsemen loping across the training field at Krasnoye Sielo, he was carried away with the headiness of that joy he had known long ago—a joy brought on by the sensation of belonging.

“My children, I am pleased with you.”

His Majesty uttered the ritual phrase that honored their work and crowned their exploits.

As one voice, they answered with a spirited, “At your service, Little Father!”, the ritual words of an equally sacred response.

The opening of the grand opera was over. The regiments headed toward their assigned corners of the maneuver grounds.

It was time for the performances of the Cadet Corps. Grand Duke Mikhaïl Pavlovitch had informed their master of the program of drills to be accomplished, and the cadets had practiced for months. And they would practice again today, as many times as necessary.

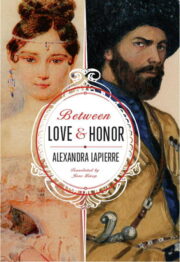

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.