He thought of it today as he rushed toward the office, his confidence renewed as he recollected the incident.

The door was closed.

None of the attendants had bothered to inform him that the emperor no longer received visitors here, nor in his immense office on the second floor. He now met with his audiences in the former headquarters of his late brother, Grand Duke Mikhaïl, the gold and green salon with its Kashmir carpet and its earthenware stoves emblazoned with the battle-ax and the lictor’s fasces.

As he retraced his steps, he was struck this time by the strange atmosphere.

The embassy attachés, orderly officers, administrative personnel, and secretaries all seemed to be in a state of agitated turmoil that he hadn’t noticed on his way in.

They seemed unusually numerous and rushed, all headed in the same direction he was going. It was impossible to pass them, so he followed the flow.

“The outcome is certain,” said one of the courtiers, “since God is with us!”

He listened attentively now, catching snatches of conversation among the small groups walking alongside him, all of whom were saying the same thing.

“Russia is not fighting for any material gain.”

“She is embarking on a crusade.”

The word rang in his ears. It had never been used at Uhlan headquarters in reference to the previous six months’ preparations for a conflict with Turkey. At Torjok, they had said that the czar was arming for war, not that he was leaving on a crusade.

“We are waging a holy war,” a young girl insisted.

His blood turned to ice.

He was familiar enough with the ways of the Winter Palace to know that this was not an idea that any of them had come up with, but one dictated by the emperor. What was the czar thinking? He had better find out fast.

“We are fighting for the triumph of the eternal faith.”

“That’s why everyone is against us,” one of the maids of honor nodded. “Monumental and contradictory forces are pitted against each other, the East against the West, the Slavic world against the Latin one.”

He stopped to take stock. He must forget his own feelings, his passion, even forget about Lisa—and calm down. What on earth were they talking about?

The affair—the crusade—had begun a few years ago in Jerusalem, Turkish territory, with a quarrel between Christians. This he knew. He recalled that the czar had been livid to discover that the Muslims had allowed the Roman Catholics to be in charge of the holy places, when the honor had belonged to the Orthodox Church since time immemorial. And Russia was the protector of the Orthodox Church throughout the sultan’s territory. Catherine II had even signed a treaty to this effect with the Sublime Porte. It was an official pact. For the sultan to have broken his word, granting Napoleon III’s Catholics all the privileges that the Orthodox Church and Czar Nicholas were due, was an outright betrayal. Ambassadors and diplomats had hastened to make the Turks admit their duplicity. But the sultan, backed up by the French and encouraged by the schemes of the British, refused to budge.

That much Jamal Eddin knew. He also knew that the czar had suggested that Russia and Europe share the scraps of the Ottoman Empire, whose demise seemed imminent.

The only detail Jamal Eddin had not picked up on at Torjok was that the European powers were extremely wary of Russia’s expansion into the Balkans and the Black Sea. That proposition had been accepted on the condition that the czar (representing Russia) be excluded when it came time to divide up the remnants of the Ottoman Empire. The czar had protested the snub, insisting that he had never intended to seize Constantinople. But it was to no avail. Europe feared his appetite for conquest too much to believe him. The result would be war—war with Turkey, of course, but also with France, England, maybe Austria, and perhaps even Russia’s long faithful ally, Prussia. Now Jamal Eddin understood.

His timing could not have been worse. What did his destiny matter when the entire country was threatened? It was utterly mad! He wanted to turn back, but something pushed him inexorably toward the antechamber of the green salon with the rest of the supplicants.

The room was crawling with dignitaries, ministers, and members of the council, who had come to discuss current affairs, quite separate from military matters. Like Jamal, each had mentally practiced the speech he would present to the czar, backed up by a thousand arguments and reasons, all the way here. It was best to be prepared and to be brief; the czar never received anyone for more than ten minutes. As a result, he saw a regular parade of visitors.

The imperial schedule was further complicated by the czar’s imminent departure for Olmütz, where he planned to meet the emperor Franz-Joseph in a last-ditch effort to keep the peace.

Jamal Eddin stepped back. What good was his energy, his eloquence, his love for Lisa in such circumstances? It was mad. He should wait for a more opportune moment. Rapidly and a little awkwardly, he turned to press against the tide and make his exit. Too late.

The orderly officer opened one side of the double doors to the czar’s office and summoned him.

“If you will be so kind as to follow me, His Imperial Majesty will receive you now.”

From the back of the salon, the emperor’s resonant voice boomed jovially.

“Come in, my boy, come in! It’s always a pleasure to see you. Come protect me from all these sharks!”

The office was crowded too. A swarm of officers huddled around maps that were spread across several tables. The décor had changed, as well as the atmosphere. The looming figure of the czar across the room was the only thing that remained as it always had been. Clad in an impressive white uniform, he was standing erect, backlit by the sunlight from the window, absorbed in the files he was poring over. Jamal Eddin was familiar with his habits and knew he would maintain this pose until the last minute. An old tactic, it was a way of making his visitors slightly nervous before he surged forth out of the shadows in all his splendor. Or in all his wrath. Over time this act had become a ritual of the imperial audience.

Jamal Eddin could not see the czar’s features clearly, but he sensed his tension and fatigue. His self-control was usually evident. Today, however, he seemed to have difficulty concentrating. He handled the dossiers absently, opening this one or that without really reading them.

“Let me just finish what I was doing, my lad. It’s good to see you. You’ll tell me all about your life in Torjok. Frankly, I’d like to be in your place, with the path laid out before me. You at least know where you’re going. I,” he said to the room at large, “I seem to endure one betrayal after another. And to try to remain faithful to what I consider my duty.

“Russia shall remain faithful to her honor,” he continued, “faithful to all she is committed to.”

The czar was no longer addressing Jamal Eddin but haranguing the assembly of officers. He chose his words carefully. He wanted everyone here to remember them and to spread them far and wide. He spoke forcefully, mistaking his adoring audience for the judgment of posterity.

“Russia will defend Christianity against all the countries fighting on the side of the crescent.”

Now he turned to Jamal Eddin, who stood at attention before the unoccupied desk.

“For you see, my boy, among the traitors and hypocrites, the Turks are not the worst. No, the worst are not those who advise the sultan and his hordes of fanatics. The worst are the faithful who betray God.”

The czar’s words made Jamal Eddin uneasy. This invective against hypocrites and the traitors, these words so familiar to him, upset him deeply.

“Actually, the worst ones are the Christians.”

Now was clearly not the moment to ask to convert to Christianity.

The czar was so perturbed at the mention of this European alliance with the Muslims, this monstrous and incomprehensible choice—against him—that he dropped one of his dossiers.

Petrified, Jamal Eddin did not move. He remained standing, heels together, arms at his sides. His heart was beating as though it would burst.

All the aides-de-camp scrambled to their knees to gather up the sheets of paper scattered on the floor.

After a brief silence, the emperor returned to the question that obsessed him.

“Is it conceivable that Russia can find no allies among her Christian brothers? That the king of Prussia and the emperor of Austria are capable of adopting Mohammed’s cause as their own?”

He straightened his shoulders and roared again, “If they dare to do that, then so be it! I place my hope in God and in the justice of the cause I defend. Russia alone will raise the holy cross, and Russia alone will follow its commandments.”

He turned back to Jamal Eddin and repeated, “I’ll be with you in a moment, just let me finish what I’ve begun.”

But he broke off again, leaving the window to walk to the chair behind his desk, where he sat down heavily.

“At ease, my boy, sit down, sit down. I’m glad to see you. You, my dear children, are my consolation and joy. What brings you here, my lad, what can I do for you? You would like to join the army of the Caucasus, to go and fight the Turks, is that it? You would like to take the occasion of this war to see the mountains again? Unless—”

A glimmer of bitterness flashed in the czar’s eyes.

“Unless you have come to ask me to send you back to your father? To take up arms against me, like all the others. You’re all the same. You come to walk all over Russia before stabbing her in the back without regret!”

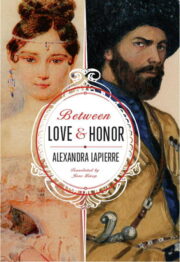

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.