One of the murids—Khadji, the steward—waved a banner, the signal for the exchange.

The interpreter left the group and galloped toward Jamal Eddin.

As agreed, Lieutenant Shamil was accompanied by thirty-five lancers—including Sacha Milyutin and Buxhöwden—the four wagons containing gifts from the czar and his own books, the forty thousand rubles, and the Chechen prisoners the Russians had promised to release.

The convoy descended the hill with some difficulty. Jamal Eddin rode at the head, like Mohammed Ghazi.

The sun shone brightly, as though it were summertime. Shamil had calculated that, weather permitting, the giaours might be blinded by it. There were stagnant puddles on their side of the riverbank, attracting horseflies that would annoy and excite their mounts.

The Russian horses shook their heads, and their tails swatted their hindquarters furiously. The officers perspired beneath their caps.

Jamal Eddin felt nothing. Not the heat. Not his own sadness, not even fear.

Though he felt nothing, his mind was active, concentrating on the adversary’s every move, and the tension of a body ready to fight. He sensed a profound, almost physical wariness of the natural setting and the men he was about to meet.

He advanced without cover onto the plain with Chavchavadze.

They were flanked by two Russian army captains: Baron Nicholas, David’s second brother-in-law and representative of the empire, and Prince Bagration, Prince Orbeliani’s aide-de-camp and representative of the royal family of Georgia to which Anna and Varenka belonged. Prince Grigol Orbeliani, who had negotiated Varenka’s liberation, was not there. He was holding down the fort at Temir-Khan-Chura with the rear guard of the army, in case Shamil had lured the czar’s forces into a vast trap.

The four officers rode at the same gait and seemed bound together by the same thought: did the four wagons really contain the captives?

There was no sign of movement from the wagons, other than that of the fat blue flies that alighted on the canvas exterior then flew away to land again on another spot.

When the four men had reached the dead tree, Mohammed Ghazi’s horsemen closed ranks. The four wagons were hidden from the Russians by their bodies, their horses, their high black papakhas, and their banners.

David and Jamal Eddin exchanged a dubious look, both reining in their mounts to slow down slightly. What did this mean?

They saw that one of the Chechens held a toddler in front of him on the saddle. The murid kept him centered before him, like a shield. David recognized Alexander, his son who was not yet two.

What was this new blackmail?

The murid broke away from the group. What was he going to do with the child?

Hearts pounding, Jamal Eddin and David came to a halt and waited for the Chechen to approach.

Amazingly and unexpectedly, the horseman spontaneously handed the little boy over to his father and retreated.

David clasped his son in his arms and hugged him to his chest.

At the same moment, three little girls jumped out of the wagons. They ran between the horses’ limbs toward their father. The prince leaped from his horse to embrace his children.

Jamal Eddin could not bear to watch this touching scene of a family reunited.

He continued riding toward the wagons, heading off to the side to avoid the rider in white.

The ranks of the murids parted to let him pass. He reached the first wagon.

He waved a hand across the canvas, chasing away the flies, and pushed back the cover. His stomach churned with anxiety. What would he find? For the first time, he gave words to his fear: were the princesses still alive?

He pulled back one of the canvas flaps.

In the dim light, he could barely make out the figures of two women, veiled and dressed in rags, sitting on opposite benches. They seemed petrified. Had they been saved? Were they free? They did not dare believe it and continued to pray in muffled, breathless voices.

The princesses were unrecognizable under the layers of shawls that covered them from head to foot. He bowed politely and apologized for having been so long in coming.

He handed them a letter that their mother, Princess Anastasia, had written them when he had visited her shortly before leaving Russia. One of the phantoms took it from his hand without a word. Anna? Varenka? The form remained silent.

She would have liked to thank him, but the stress of captivity, the anxiety, the terror leading up to this day, and the apprehension that had filled these last hours had robbed her of her faculties.

She managed only to say, “My sister is in the second wagon.”

He nodded, left her, and approached the second wagon.

A figure was standing among the other seated ghosts. The princess Orbeliani. He knew her with absolute certainty, even smothered in these rags. Varenka, the love of his youth, his first love.

Though he could not read her expression, she saw his face clearly through the weave of her veil. She had recognized him instantly, and no wonder. Jamal Eddin, her dancing partner of so long ago, had been the primary subject of conversation for the many months of her captivity at Dargo-Veden.

Jamal Eddin, the eldest son, the kidnapped son, the cherished son of the imam.

Shamil’s three wives, his daughters, and their governesses—in fact, all the women in the seraglio—had listened avidly for rumors, stories, and spies’ reports that circulated in the village. They had followed Jamal Eddin’s path to his father’s fortress, from Poland to Saint Petersburg, Moscow to Vladikavkaz, Khassav-Yurt to the Mitchik.

For every one of them, his return was a personal victory, the triumph of their beloved master over the infidels, the triumph of God’s chosen over the treacherous giaours, a victory over the will, the wealth, and the power of the Great White Czar.

The princesses, too, had thought of the imam’s son every day of their captivity, even more than the other women. They had hoped and prayed for Jamal Eddin, anxiously awaiting his arrival every day.

Today they owed him their lives, and Varenka Ilyinitchna, Princess Orbeliani, knew it. And many other things as well.

She knew that, waltzing in his arms at the Peterhof-Alexandria cottage, her heart had been in his keeping. She had loved Jamal Eddin when she had been very young, loved him secretly, passionately, despite her own natural reserve and the calm her own shyness imposed, despite the outward appearance of chastity she had maintained.

She was still aware that back then, had he been more insistent and less sensitive, he could have dishonored her.

She knew that Shamil had considered keeping one of the prisoners to offer his son as a bride. He had chosen Princess Nina Baratachvili, the penniless niece of the Orbelianis and the Chavchavadzes. Of all the hostages, she was the only one who had never been married or had children. When Princess Nina, a virgin of eighteen, found out, she was horrified at the prospect of being abandoned by her aunts here in the mountains and handed over to a Chechen like chattel. She had flown into a rage, insulting the imam, and Varenka had avoided the potentially serious consequences of her tirade by offering herself in the princess’s place. One or the other of the prisoners, it was all the same to Shamil. He simply wanted to save a Russian princess for his son, and his own wives had assured him that she was young and pretty. The violence of David Chavchavadze’s outrage at the mere suggestion of delaying the liberation of the princess Orbeliani had prompted him to drop the idea.

However, Varenka knew that she had been widowed, that she was free now, and that, perhaps, it was still a possibility.

But now, she knew it was all over.

It was not just seeing Jamal Eddin again, here, in these circumstances, that rendered her speechless, but a thousand other emotions that filled her heart as well.

They looked at each other, both incapable of saying a word.

Suddenly the horseman in white, on foot now, appeared out of nowhere. With a brutal tug, he silently pulled down the canvas flap, and Varenka disappeared from sight.

It was not yet time for the two brothers to proceed with the exchange or even to acknowledge each other. Custom dictated that Prince Chavchavadze and the imam’s heir greet each other first.

Mohammed Ghazi, pale and tense, spoke only to David. He began a long and solemn speech, of which the interpreter translated bits and pieces.

“My father has ordered me to tell you that, if your women suffered during their stay with us, their pain was not inflicted intentionally, but out of lack of means and our own lack of familiarity with the way they should be treated. My father wishes you to know they are being returned to you today worthy in every respect, pure as lilies and protected from all eyes, like the gazelles of the desert.”

The prince bowed and replied with equal ceremony.

“I have been informed for some time, in my wife’s letters and those of my sister-in-law, of the respect the imam has shown toward my family. In writing to your father myself, I have had several occasions to express my gratitude in this regard. Now I beg you to present to him my most sincere thanks.”

The formalities had been observed down to the last detail. Mohammed Ghazi could now turn to Jamal Eddin.

They stood politely, face to face.

One wearing the blue, purple, and gold uniform of the lancers, the other a cherkeska, they were the same height, with the same youth and elegance, and the same nobility. Two sides of the same coin.

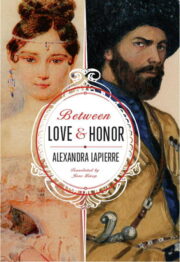

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.