Then he noticed Milyutin and Buxhöwden standing beside his other two sons.

He turned to ask the interpreter, “Who are they?”

“Your son’s boyhood friends, who wanted to pay you their respects,” the interpreter explained.

“I thank them,” said Shamil.

Jamal Eddin disengaged himself from his father’s embrace and stood up.

His friends asked if they could bid him farewell, Russian style.

“Why not?” Jamal Eddin replied.

With spirit and élan, each one embraced him and kissed him three times.

Shamil was worried that seeing Jamal Eddin in the arms of the giaours would make a very bad impression upon his people. In an effort to justify their behavior, he explained loudly to those around them, “These three boys grew up together!”

The imam then rose to greet Milyutin and Bux politely. He ordered Mohammed Ghazi to accompany them back to the other bank, with the protection of a hundred murid warriors.

This time, the three friends’ farewells were final.

Jamal Eddin embraced his companions one last time and asked them not to forget him. He also asked them to send Prince Orbeliani his regrets at not having made his acquaintance.

Courteous and gallant to the last.

The interpreter and the officers rode back across the river and returned to the Russian contingent on the hill.

Now that the Russians were gone, an unrestrained volley of gunshots and whoops of celebration at the return of the imam’s son broke out.

The echo of exploding guns and the clamor of men would ring in Bux’s and Milyutin’s ears for a long, long while.

They turned back, searching for the horseman in black more noble and elegant than all the rest. They saw only his back.

Riding next to Shamil, Jamal Eddin climbed the boulder in the direction of the woods. They zigzagged between crews of men, who were busy uprooting the shafts of banners, gathering the standards and carpets, and rolling up the tents. The army was packing up.

Father and son rode off toward the forest.

They were of equal strength and height. The older man rode a gray mare, the younger a big white stallion. The panels of their turbans fell in straight lines to the small of their backs.

For a moment, Jamal Eddin seemed to float above the abandoned parasol, above the teeming crowd.

Then suddenly, as though the mountain had swallowed him up, he disappeared.

Neither Sacha Milyutin nor Count Buxhöwden nor Prince Chavchavadze nor any of the other officers in their company at the exchange ceremony would ever see the “rebel’s son” again.

But they would tell of that intense moment, of watching Jamal Eddin disappear down the mountain path into the vastness of the Caucasus, carrying within him all that remained of the honor of men.

EPILOGUE

All That Remained of the Honor of Men Dagestan and Chechnya

1855–1858

“At first, we received letters from him,” Elizaveta Petrovna Olenina wrote in 1919, at the age of eighty-seven. “I learned that he had tried to escape three times, and that three times he had been recaptured by his brother Mohammed Ghazi, whose prisoner he had become.

“It was my own brother, Alyosha, then stationed at the garrison at Stavropol, who transmitted the messages that Jamal Eddin had managed to pass through his father’s lines.

“At the beginning, we had news from him fairly regularly through Alyosha, and he passed on what was being said in the forts of the Caucasus about what was happening to my fiancé.”

Rumor had it that Jamal Eddin had set about his task the very day after his return. He explored the mountains of Dagestan and the forests of Chechnya, visited all of his father’s mountain eyries, studied the state of his fortifications, passed his troops in review, and methodically examined arms and equipment.

The conclusions of his investigation were scarcely surprising and confirmed what he had feared. The Montagnards were too few in number. Their weapons were old, worn out, and defective. The population was splintered by interclan squabbles, and the villages were ready to betray Shamil at the least sign of weakness.

Over the long term, the murid resistance was doomed to fail.

He sat down with his father for a serious discussion about all this. He tried to describe the immense wealth of the new czar, the power of his armies, and the sheer size of his empire.

The current succession of Russian defeats in the Crimea, however, did not help his cause.

Jamal Eddin’s argument only reinforced Shamil’s conviction that victory was imminent and that, more than ever, he should continue to harass the infidels. The holy war must go on.

The young man tried again, leaving aside the power of the Russians and concentrating on the unfortunate state of the Montagnards. Soon there would not be a single fighter left in the Caucasus—no more men, young or old. No more men at all.

Years of bloodbaths had decimated the population, and every new massacre weakened them further. The ranks of cavalry were too sparse, and their muskets were not powerful enough. If Shamil wanted his people to survive, he must seek peace with the enemy.

It was exactly the same thing that the imam had heard so long ago, at Akulgo: “If we don’t negotiate with them now, when this is what they want, they will kill all our men, abuse our women, and enslave our children. Give your son to the Russians, since that is what they ask. And play for time.”

Negotiate now. Jamal Eddin’s words echoed the past. Negotiate now, right away, when the invaders are busy elsewhere and in a difficult position themselves. Negotiate with them now, when they’re still clamoring for negotiations.

Afterward, it will be too late.

The siege of Sebastopol was over. Yes, the Russians had lost the war against the Europeans. But they had learned a great deal from their contact with modern and powerful troops. And now they would be free to concentrate on another front.

Prince Bariatinsky, the new commander-in-chief of the Armies of the Caucasus, was a personal friend of Alexander II. He would have every means at his disposal to bring this conflict to a positive end. And he was of an entirely different mettle than Grabbe and most of his predecessors.

Jamal Eddin emphasized that the situation was urgent. If he negotiated today, his father could still obtain the essential conditions he desired: religious freedom and possession of the land. As for the rest, he should let it go.

It was said that his words broke Shamil’s heart.

They wounded him to the core, and then they sent him into a mad rage.

His son was an agent, in the pay of the infidels!

The giaours’ henchman!

This is what his son had become? A hypocrite? A traitor?

This was probably the only reason the Russians had agreed to send him back to the Caucasus—to spy, to lead them astray, to corrupt his own people!

Wasn’t that the objective of the Great White Czar’s entire plan? Wasn’t that why he had kidnapped his son, kept him, and educated him?

He had succeeded in turning the son against the father, in alienating his child and defiling him.

Profoundly hurt, disappointed by his efforts, his love betrayed, Shamil suffered anew because of Jamal Eddin.

He began to avoid spending time with his son and soon became suspicious of his influence.

When young Mohammed Sheffi, fascinated by his older brother, also began to speak of the necessity of peace, their father’s wrath knew no limits.

Fearing contagion, the imam took away every vestige of Jamal Eddin’s Russian past, every impure object he had brought with him from the land of the infidels. He had thought it would be possible to let his son live as he liked here in the mountains. He had been wrong.

Shamil burned his books, his novels, his poetry, his maps, and his works of grammar. He burned the instruments he used to study physics, his sheet music, and his painting supplies.

The imam invited his son to concentrate on reading the Koran, exploring Sheik al-Buhari’s Book of Hadiths, and learning Arabic. He asked him to take instruction with the mullahs Shamil had chosen and not to leave the madrassa until his masters deemed him worthy and ready. He gave his son extensive access to his own library, which was replete with the knowledgeable works of his own masters and precious manuscripts that he himself had collected.

In Tiflis, it was rumored that Shamil wanted Jamal Eddin to marry. He had chosen for him the daughter of the naïb Talguike. She was said to be young, beautiful, and submissive. His purpose, no doubt, was to make his son an integral part of the life of his people and the future of Dagestan.

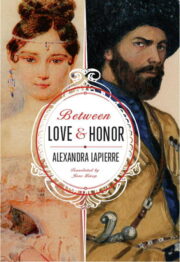

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.