“And you’re not a true Muslim, Ullou Bek. The infidels pay you, and you serve them like the dog you are,” she snapped back.

“Yes, they pay me. And they’ll pay all of you, if you take a step toward them. The first to do so will receive the best treatment and the finest gifts. Those who linger will receive less. Go welcome them at the gates of the village, go with your women and children, go to them freely. They’ll ask nothing of you, except that you live in peace with the Great White Czar. What do you have to lose?”

Bahou-Messadou straightened up to her full height and threatened the men of Ghimri. She knew why they hesitated.

“The vengeance of Shamil! Remember what he did to the khans of Avaria and the people of Untsukul, and all those who surrendered to the Russians.”

“The Russians will defend you. If you are protected by the power of the Russian cannons, Shamil cannot harm you.”

“Will they defend you the way they defended Kunzakh and protected the khans there?” Bahou answered, with more than a little irony.

“As they are avenging the khans of Avaria at this very moment, taking back the lands that belong to them. As they burned the villages of Arakhanee, Irganai, and Akulgo as a reprisal for Shamil’s actions at Kunzakh. As they will burn Ghimri and kill you all.”

“Don’t listen to Ullou Bek. The Russians have sent him here to lull you with his words. They’ll kill you anyway. Since there aren’t enough of you to defend the village, you should burn it yourselves, run with what remains of the harvest, and join Shamil. Then the giaours will find nothing to eat, drink, or steal here.”

Old Urus-Datu was still skeptical.

“What about the treasure?”

“The Poles will take it into the forest with us.”

Ullou Bek shook his head back and forth in disapproval with a low whistle.

“In the forest,” he said with scorn. “The Russians will follow you, and believe me, they’ll catch you. But if you offer them something amounting to a bargaining chip”—he gestured offhandedly toward Bahou-Messadou—“something they’re interested in, then they’ll offer you something in compensation. If not…”

He raised a hand toward the ruins of the mosque and the charred watchtowers.

Bahou-Messadou spit on the ground at his feet.

“If you’re afraid, Ullou Bek, give your saber to the women and hide beneath our veils.”

In a lightning gesture, the head of the council blocked the khan’s kinjal in midair in its trajectory to behead her.

“Take her away,” he ordered. “Throw her in the pit with the other hostages.”

The pit, which the giaours called “Shamil’s well,” was just outside the village. It consisted of a hole that had been dug vertically into the rock face, with an entry hatch. It had been the titanic work of Russian prisoners, whom Shamil considered his slaves. He forced the hardest of tasks upon them, with the ultimate purpose of exchanging the wealthier ones, the officers, for exorbitant ransom.

These captured men from raids on the Russian forts and the villages that had surrendered to the infidels, hostage taking, horse thieving, and the theft of arms and livestock—all this made up the treasure of Shamil’s war chest.

Shamil despised luxury and ostentation and was not interested in acquiring wealth for himself. His life was based upon piety, discipline, and austerity. Though he was keen to acquire, personal interest was not an element of his greed. Unlike most of his fellow citizens, he had never intended that the treasure of Kunzakh serve his personal needs or desires. The booty was a tool, nothing more, a means to resist. He counted on using it to buy the favor of the tribal chiefs and to pay his spies, the Armenian merchants, and the Polish soldiers he recruited in the forts. He planned to use it to acquire the rifles that the English adventurers, determined to impede the czar’s march toward India, had offered to the Chechens and the Cherkesses—for a price. He wanted to bargain for horses in Kabarda, a city famous for its swift and hardy stallions, so that he could establish a network of intertribal messengers. And he wanted to have a medal struck to honor the heroism of his murids and compensate them for their feats of courage. He wanted to take care of the families of the wounded and the dead. And much more. From the least significant decisions he made to the most brutal cruelties he committed, all were motivated and justified by his dream of a strong and free Muslim state.

The Russian prisoners languished on the straw of Shamil’s well with eight hostages from Untsukul, the neighboring community he had punished for treason. These prisoners’ fathers had been decapitated, and following the traditional treatment of friends and relatives of traitors, the executioner had gouged out their eyes. As for the infidels, blinded by years of reclusion in the tomb, they dug each day a little deeper; their hunger, thirst, and exhaustion were such that they could barely stand up. This was the little group Bahou-Messadou was to join in the stinking obscurity of the pit. She well knew the fate reserved for enemy families.

To add to her pain, she was informed that her daughter-in-law, who had looked everywhere for her and finally come to the mosque, had been taken too.

Fatima followed her down the long ladder, the toddler still strapped to her back. The little boy wiggled, furious at being bound up like a baby.

Face-to-face in the dark, the two women peered at each other in the obscurity, crying out as one, “Jamal Eddin is not with you?”

“Calm down,” Bahou soothed, “he probably ran away with Patimat.”

The Russian prisoners, excited at the prospect of imminent freedom, paid no attention to them. But the blind captives of Untsukul, the village where Fatima had grown up, recognized her voice. They crowded forward to chase the two women, eager to get their revenge for Shamil’s cruelty. They rushed at them, their hands feeling for the one who carried the baby. She flung them off and backed away. As they groped for the child, two of them felt something warm and wet on their palms. It was their own trickling blood. They had grabbed two blades with their hands.

No one had thought to take away the women’s kinjals, and they used them now against the men, who were not armed.

Suddenly the thunder of hooves above them vibrated through the air of the cavern, and they heard gunshots. Everyone stood still and listened. Nothing. There was not another sound. Once again they were cut off from the world.

Then once again they heard cries, this time what sounded like orders. The trap opened and the ladder was thrown down.

“Descend.”

The sudden brightness prevented them from distinguishing who stood at the edge of the hatch. A stocky, veiled figure struggled above them. It was Patimat, Shamil’s sister. She fought them all, calling the hypocrites traitors, swearing that Allah would not let their crimes go unpunished.

Bahou was afraid the elders would throw her daughter into the pit.

“Descend!” she cried.

Patimat’s foot had barely touched the straw when Fatima accosted her.

“Jamal Eddin?”

“He was with the Poles.”

“They took him with them?”

“The Poles don’t know the mountain. As if they could cross the Avar Koysu on mules!” Patimat’s lip curled scornfully. She had never understood why her brother kept renegade Christians under his roof and let his son play with them.

“Ullou Bek captured them.”

“All five?”

Patimat nodded. “All of them, with the treasure.”

Everyone here knew what that meant. By now, their heads were swinging from the pommel of the bey’s saddle.

“The council decided that no one is to leave Ghimri,” Patimat continued, breathless. “Urus-Datu is preparing to meet the Russians. He is going to negotiate with them, with Ullou Bek as intermediary. The women and children are to stay behind, to welcome them to the village.

“As for Jamal Eddin, I don’t know,” Patimat said, her tone sharp with fury and anxiety. Her voice was hoarse, with the guttural inflections of the women of Ghimri. Unlike the other women, though, Patimat was tall like her brother. She shared his ardor, his piety, and his authority. Since her husband’s death, she had ruled over Shamil’s seraglio. Her passion for him was limitless, and she only differed with him—and only in the intimacy of their private quarters—on one point: his insistence on austerity. If it had been up to her, she would have established the power of the house of Shamil through the possession of fine arms and beautiful clothes. So she devoted a good deal of energy to adding to her collection of fine fabrics and kinjals with chased handles, squirreling away all the spoils she could find under her bed. As for her brother’s enemies, her hatred for them guaranteed her family’s safety here in the pit, at least for the time being. The punishment of the Untsukul traitors struck her as far too lenient. They deserved much worse for having made peace with the infidels. Patimat had also kept her dagger and fully intended to use it.

The three women sat down. More than by the stench of the place, they felt sullied by the proximity of the Russians.

Bahou-Messadou had taken her grandson on her lap and cradled him softly. She rocked him to and fro, chanting a variation of the “Ballad of Shamil,” the war song his horsemen sang as they left for battle, in the metallic voice that was hers alone.

Awake, people of the mountains,

Bid farewell to sleep,

Unsheathe young sabers and draw your kinjals,

I call you in the name of God.

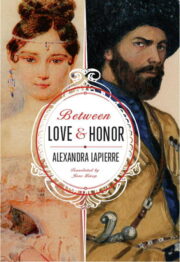

"Between Love and Honor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Between Love and Honor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Between Love and Honor" друзьям в соцсетях.