‘Come, my darling,’ she said. ‘We are going on a journey.’

The Dauphin sprang up. ‘Now … Maman? Now? Where do we go? Are the soldiers coming with us?’

‘We shall go to a fortress where there are many soldiers. Come now. I will help you to dress. Be quiet, for it is late and there is not a moment to lose.’

‘These are girls’ clothes!’ cried the Dauphin in dismay. Then gleefully: ‘Is it a masked ball, Maman?’

‘I said, be quiet. It is important to be quiet.’

‘Are you coming?’ he whispered.

‘Yes … but later. Do as I say, or you will be brought back and there will be no journey. Do not say a word until you are told you may.’

The Dauphin nodded conspiratorially and allowed himself to be dressed in a girl’s gown and bonnet.

‘Now,’ said the Queen. She led the way swiftly through silent rooms, down a private staircase to that exit at which Fersen had made sure no sentry should be placed.

The Queen went ahead of her children and looked out. Almost immediately a cloaked figure appeared from the shadows. It was a coachman, and Antoinette recognised him by his gait. She could have wept with joy and gratitude. She might have known he would not fail.

No word was spoken. Fersen took the Dauphin’s hand; Madame de Tourzel was holding fast to Madame Royale. Fersen led the way to where the fiacre was waiting, and Antoinette returned to the salon.

At eleven the Queen intimated that she was tired and would retire for the night.

Her women undressed her, and never had they seemed so slow.

‘Pray,’ she said to one of them, ‘order the carriages for tomorrow morning. If the weather is as good as it has been today I should like to go for a drive.’

‘Yes, Your Majesty.’

The Queen yawned.

‘Your Majesty is tired?’

‘It is the heat, and the conversation in the salon seemed even duller than usual.’ While they removed her headdress she watched them through half-closed eyes. She wanted to shriek at them: ‘Be quick. Every moment is important.’

At last they drew the curtains about her bed, and she heard the door close.

Immediately she was out of bed; she dressed herself in a simple grey silk dress and put on a black hat with a thick veil. Her fingers were clumsy, for she was unused to dressing herself. She wondered how Elisabeth was faring. But Elisabeth would be calmer than she was. No doubt Elisabeth was already joining the fiacre in the rue de l’Echelle.

She wondered about Louis. He too had to make ready for his escape. He would find it even more difficult. La Fayette would pay his nightly visit to the Tuileries and would spend some time with the King. A good deal depended on how soon the King could dismiss La Fayette without arousing his suspicions.

But she must think only of her own escape which would need all her care.

Fully dressed now in the hat with the heavy veil, she was unrecognizable. She drew the curtains about her bed again and slipped out through the private door, down the private staircase.

As she came to that door through which the children had left, she saw the tall figure of a guardsman. She caught her breath in a moment of fear, although she knew she was to meet such a man who would conduct her to the fiacre. What if they had misjudged their man? What if he, like Madame Rochereuil, was a traitor after all?

His voice was soft as he whispered: ‘All is well, Madame. Follow me.’

Her heart leaped. She could trust Fersen to have made all the arrangements.

Louis was yawning effectively, letting La Fayette see that he was weary of his company; but it was not as easy as it had been to dismiss a general. La Fayette talked, and Louis must not draw attention to his desire to go to bed. Marat’s article might be remembered, in which case La Fayette might consider it expedient to double the guard.

But at length La Fayette, in consideration of the King’s yawns, took his leave; but Louis’ troubles were only just beginning. He must submit to his coucher, for the etiquette of the Court had not been so far forgotten as to allow the abandonment of such a traditional ceremony. So Louis was put to bed and, according to the old custom, his valet must sleep in his bed chamber, with a cord attached to his wrist and to the King’s bed-curtains, so that if the King needed him, all he had to do was reach for the curtains and jerk the man awake. How to escape from the valet, who was a man who could not be trusted with the secret, had occupied the minds of them all for many nights. It had been arranged that the King should go to his bed, have the curtains drawn as though he wished to settle down to immediate sleep, and while the valet went into his closet to undress, dart out from behind the curtains into the Dauphin’s bedchamber which adjoined his. There he would pick up the clothes which were ready for him in the Dauphin’s room – a lackey’s suit and hat, and a crude wig, and then tiptoe down the secret staircase with these to one of the lower rooms where Guardsman de Maiden who was in the secret would help the King to dress.

So the King of France, barefooted and in his nightgown, escaped from his valet and, being dressed in these humble garments, walked calmly out of his Palace across the courtyard past the guards who mumbled a sleepy good night, and out into the streets, across to the Petite Place du Carrousel to the rue de l’Echelle and the fiacre.

It was disconcerting to find that the Queen, who should have left the Palace earlier than the King, had not yet arrived.

Antoinette followed the guardsman.

They had escaped from the Palace, and her spirits were rising. Never again, she thought, shall I live a prisoner in that gloomy Palace.

The guardsman was a little way ahead; she hurried to keep up with him. Who would have believed that escape could have been so easy? In five minutes, she thought, I shall be with the children. They are safe … safe with Axel.

It was strange to be out walking in the streets of Paris. She realised then how little she knew the city. I should never have found the fiacre by myself, she thought.

Suddenly she saw that the guardsman had halted, and in a second she understood why. Coming towards them was a coach before which walked the torchbearers. The guardsman was signalling her not to come forward, and looking about her, she saw an alley and slipped down it. The light from the torches shone on the dark wall of the alley. She lowered her head for she had recognised the livery of La Fayette’s men and she knew that the General would be in his coach.

The coach passed so close to her that she saw La Fayette sitting in it. For an instant her heart felt as though it would choke her. Holding the veil tightly about her throat, she turned and began walking slowly down the alley.

The sound of the carriage wheels had died away and then she heard footsteps behind her. She dared not turn. Her heart was beating madly. ‘Oh, God,’ she prayed, ‘let me reach the fiacre. Let me reach my children.’

‘Madame.’ She felt she wanted to shout with relief, for it was her guide. ‘That was a near thing. If the General had seen Your Majesty … ’

‘He would not have recognised me,’ she said, for the man was trembling.

‘Madame, it is not easy for you to disguise yourself.’ He was frowning. ‘Let us go another way to the rue de l’Echelle. I am afraid that if we take the route we planned we may meet more carriages.’

‘You are right,’ she said. ‘Let us do that.’

So they walked and, after ten minutes, the man admitted that he was not sure where he was. He was not so well acquainted with this part of Paris, and these back streets were such a maze.

‘They will be waiting,’ she cried frantically. ‘They will think I have not escaped. We must find them … quickly.’

But they were lost in that maze of streets and, when they tried to retrace their way to that spot where they had met La Fayette’s carriage, they could not do so. For half an hour they sought to find their way and, when they finally reached the rue de l’Echelle, it was to discover that the others were in despair, having been waiting for almost the whole of an hour.

Antoinette took her place in the ancient fiacre; she felt too emotional for words; all she could do was take her sleeping children in her arms and hold them against her.

Fersen climbed into the driver’s seat and whipped up the horses. Precious time had been lost, and in an endeavour such as this each minute was important.

Through the narrow streets went the fiacre, Fersen alert for any sign that they were followed. The occupants of the fiacre scarcely dared speak to each other. Many possibilities occurred to them; they would feel greatly relieved when they had left Paris behind them.

At length they came to the Barrier, but the berline was not at the spot where Fersen had arranged that it should be waiting for them.

He drew up and looked around him in consternation. There was silence all about them. Fersen descended and went to the door of the fiacre.

‘Something must have happened,’ he said. ‘There may have been an alarm which caused them to move from this spot. I will leave the fiacre here and search awhile. It cannot be far away.’

After half an hour Fersen found the berline; it was about half a mile away and it had not been visible because the lamps were covered up. The driver had been alarmed by the long delay and, when horsemen had ridden past, had felt it necessary to move from the appointed spot. Fersen then drove the fiacre to the berline and the royal family moved from one to the other.

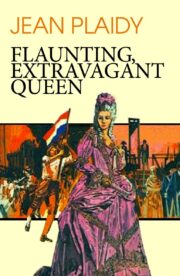

"Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flaunting, Extravagant Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.