The trail sloped up and to the left, delving deeper into the towering trees. He kept a steady pace, his boots hitting the rocky earth at an almost rhythmic pace. The bare, spindly branches extended over him in a weblike canopy, shielding him from the worst of the wind, but the bitterness of the day still chilled the exposed skin of his face.

His father had taken this walk nearly every day, Gran had said. Why? What had the land held for him? Perhaps he had been soaking it in. Enjoying the last of his time as master of the hard-won estate and the prosperity that he had earned and lost in the space of a decade and a half.

Before anyone else knew the dire state of their finances, he had already been saying good-bye.

Colin kicked a stone, sending it flying through the underbrush. A warning might have been nice. The selfishness of it all was hard to comprehend and impossible to forgive. Damn it all. This walk wasn’t having the intended effect. His breath came out in abbreviated puffs, and despite the cold, sweat trickled down his back.

He was about to turn around to head back when the stone chimney of the gamekeeper’s cottage came into view, its gray rock nearly blending in with the clouded skies behind it. It was probably best that he stop to rest before he soaked through his clothes and caught his death.

Slowing as he approached the tiny cabin, the barest hint of a smile lifted the corner of his lip. It looked exactly the same as it had a decade ago, with its squat walls covered in ivy and its uneven, thatched roof looking like an overgrown mop of hair. It sat right on the edge of the meadow, with a view to the mountains beyond through its two back windows. Perhaps “windows” wasn’t the right word—they were just open portals, covered by sturdy shutters that swung out on ancient hinges.

He’d spent many an afternoon in the place, exploring, reading, pretending to live alone in the woods. His pulse settled as he walked up the gravel path and stomped his feet on the flagstone stoop. It was like stepping back in time, standing here again. An icy blast of wind assailed him, and he quickly lifted the latch and let himself in.

Almost instantly, he came to an abrupt stop.

He stood in the doorway, frozen in a way that had nothing to do with the frigid air buffeting his back. Breathing deeply, he looked around the dim interior. The exact essence of his father was here—the scent of linseed oils and earthy pigments, the Spartan furnishings and bare windows, the open painter’s box set upon the single small table in the back of the room.

But the most significant of all was a simple easel set up beside the window near the back corner. On it a single canvas waited, tauntingly averted from where he stood.

Dear God.

Colin swallowed, his eyes riveted on the open frame of the back of the canvas. His heart beat so hard, the pounding seemed to ricochet through his head. Rioting hope propelled him forward, like sails catching wind for the first time in days. Please, please. He kicked the door shut behind him before rushing forward, the anticipation stealing the air from his anxious lungs. This could be it—everything he had hoped for. Everything that he had come here seeking.

Coming upon it, he paused, pressing his eyes closed. Sucking in a strangled breath, he sent up a quick prayer and stepped around the easel.

Blinking, he stared in astonishment at the sight before him, unable to fully absorb what he was seeing. It couldn’t be. It couldn’t possibly be. He rubbed his gloved hands over his eyes, pressing hard. Dragging in a deep breath, he opened his eyes, only to confirm what he already knew he would see.

The canvas was blank.

Chapter Twenty-seven

Colin dropped to the stool beside the easel, his body seeming to lose all rigidity in the face of the discovery. He shook his head, staring at the canvas. Nothing. Emptiness. The words described the canvas, the day, and the suddenly absent emotions within him.

Logically, he knew the anger would come later. He knew he’d fight fury as he stood in front of Beatrice and told her that all he had to offer was his word. There was no doubt he’d be consumed with resentment when he was forced to move his family to God only knew where and went begging to his aunt to sponsor his last year at the Inns of Court.

But not now.

He reached out, running his hand over the blank canvas, primed as if only moments from being used. The painter’s box stood open, with brushes lined up and pig bladders full of premixed paint, everything ready to start fresh. It was as if his father had just stepped away, fully intent on returning to begin his next work.

Only . . . he hadn’t. And he never would again. And despite it all, Colin missed him. He was unreliable, infuriating, and at times neglectful, but he was still Colin’s father, and damn if he didn’t miss him.

He bowed his head, rubbing his hands up and down the tops of his legs. He was gone, and Colin would never see his face again. Never shake his hand, or argue with him, or see him across the table at supper.

With a long, deep sigh, he came to his feet. It was too cold to linger in a place that couldn’t help him, especially with the day dipping toward evening. He had taken two steps toward the door when he looked up and saw a figure. He jumped back in surprise, his body tensing as his mind ran a second behind his instincts.

His father was staring him right in the face.

Colin’s heart, his lungs, his brain—all of them stopped in an instant, and then everything came roaring back to life all at once. Not his father—a portrait of his father. Perched on a low shelf beside the door, a large canvas leaned against the wall. He rushed toward it, soaking in the sight of his father, perfectly rendered by the man’s own hand.

It was beyond incredible—it was astonishing. He stared back at Colin with the light of devilment in his eyes, so well painted as to look three-dimensional. God, it looked exactly like him. He hadn’t realized just how faded his memory of his father’s face was until that moment, when his angled jaw and broad brow came into sharp focus.

Despite the freezing temperatures, his blood warmed, pumped with renewed vigor through his veins. God, how he’d missed him. To see him again was like laying eyes on scotch after a month of water. The emotions assailing him were so sharp as to almost burn, searing their way through his chest and gut. All the anger, the resentment, all of the bitterness of the last eight months fell away like a broken shell.

It was several minutes before he could pull his gaze away from his father’s likeness and take in the rest of the picture. Behind him, the rugged Scottish landscape rose toward the heavens, with brilliant green grasses and leaves that seemed to move in an invisible wind. Wildflowers dotted the sloping meadow, and the rocky outcrops of the base of the mountain glistened with falling water.

It was masterful.

All those years he had set aside the landscapes that had been his first love had done nothing to diminish the talent. In fact, it seemed to have grown—Father’s first works didn’t have nearly this level of detail. Colin knew his father had grown disenchanted with portraits lately, but he rather thought it was painting altogether. But the joy in this picture was undeniable.

The landscape was that of the view from the cottage—the land Father had been so damned pleased to own. The estate! Colin had been so caught up in the revelation of his father’s only self-portrait, of seeing his face and experiencing the landscape, he had completely forgotten what the painting meant.

Freedom.

He finally had something to give to Beatrice—something of worth that could put them on equal footing. He could already imagine her delight, her joy at such a perfect gift. Mind made up, he pulled the canvas down from its shelf and started for the door. At the last moment, he doubled back and grabbed the primed canvas from the easel. Barely pausing to shut the door, he hit the trail running.

“Lady Beatrice, what a surprise.”

Oh, drat and blast, where had he come from? Beatrice turned slowly, nodding with a brief bob of her head. “Mr. Godfrey. I didn’t realize you were still in the city.”

She pulled her cloak more tightly around her, a not so subtle hint that it was cold and she didn’t wish to stand in the street and talk to him. She exchanged a glance with her maid, but the girl misinterpreted her silent plea and dropped back to give them privacy.

“Indeed. Is it because of the vitriol published about me in a certain magazine that you assumed I might escape to the country, or because you thought I might have given up and accepted the position my father so keenly wishes for me to take?”

Beatrice could actually feel the blood draining from her face. A very, very bold statement on his part. Good Lord, had Colin been right after all? If Godfrey knew she was the author of the letters, what, exactly, did he want with her? Despite the fact they were in the open for anyone to see, she suddenly felt extremely vulnerable.

“Neither, of course. Just that so many have already left the city for the winter.”

He shook his head, looking at her as though she were a profound disappointment. “I knew it was you the moment I saw the second cartoon, you know.”

At least now she knew where she stood. She stiffened her spine and lifted her chin, refusing to be intimidated by the man. “Why? Because you so thoroughly recognized yourself? If you didn’t wish for the world to know of your underhanded tactics, you should have refrained from using them on me.”

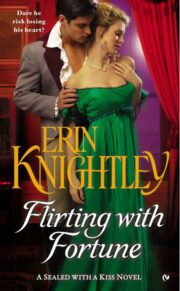

"Flirting With Fortune" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Flirting With Fortune". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Flirting With Fortune" друзьям в соцсетях.