Jessie had not left the house, and when Hagar sent for her, before I left, to tell her that I had decided to use her services, she was delighted.

” Jessie will call on you regularly at the Revels,” declared Hagar.

“And you must take her advice. Now someone shall drive you back. And when you get there you should rest.”

Simon was not at home, so one of the grooms drove me back. Ruth came out in some surprise when she saw how I had returned, and I hastily told her what had happened.

“You’d better go straight up and rest,” she said.

“Ill have dinner sent up to you.”

So I went up and Mary-Jane came to me to make me comfortable; and I let her chatter on about her sister Etty, who some months back had fainted in just the same way.

I looked forward to a leisurely evening, reading in bed.

Mary-Jane brought up my dinner, and when I had eaten it she came back to tell me that Dr. Smith wanted to see me. She decorously buttoned my bed-jacket up to my neck and went out to say that I was ready for the doctor.

He came into my room with Ruth, and they sat near the bed while he asked questions about my faint.

“I understand it’s nothing to worry about,” I said.

“Apparently it’s the normal occurrence at this stage. The midwife told me.”

” Who?” asked the doctor.

“Jessie Dankwait. Mrs. Redvers has the utmost faith in her. I have engaged her for the great occasion and she will be coming to see me from time to time.”

The doctor did not speak for a while. Then he said:

” This woman has a very good reputation in the neighbourhood.” He leaned towards the bed smiling at me. ” But I shall satisfy myself as to whether she is practised enough to take care of you,” he added.

They did not stay long and after they had gone I lay back luxuriously. It was a. pleasant feeling to know that all ms being taken care of.

It was two weeks later, when my peaceful existence was shattered, and the horror and doubts began.

The day had been a glorious one. Although we were in mid-September, the summer was still with us and only the early twilight brought home the fact that the year was so advanced.

I had passed the day pleasantly. I had been along to the church with Ruth, Luke and Damaris to take flowers to decorate it for the harvest festival; they had not allowed me to do any of the decorating, but had made me sit in one of the pews watching them at work.

I had sat back, rather drowsily content, listening to the hollow sound of their voices as they talked together. Damaris, arranging gold, red and mauve chrysanthemums on the altar, had looked like a figure from the Old Testament, her grace and beauty never more apparent. Luke was helping her—he was never far from her side—and there was Ruth with bunches of grapes and vegetable marrows which she was placing artistically on the sills below the stained-glass windows.

It was an atmosphere of absolute peace—the last I was to know for a long time.

We had tea at the vicarage and walked leisurely home afterwards. When night came I had no premonition that change was near.

I went to bed early as was now my custom. The moon was nearly full and since I would have the curtains drawn back, it flooded my room with soft light, competing with the candles.

I tried afterwards to recall that evening in detail, but I did not know at that stage that I should have taken particular note of it; so looking back it semed like many other evenings.

Of one thing I was certain—that I did not draw the curtains on either side of my bed, because I had always insisted that the curtains should not be drawn. I had told Mary Jane of this and she bore me out afterwards.

I blew out my candles and got into bed. I lay for some time looking at the windows; in an hour or so I knew that the lop-sided moon would be looking straight in at me. It had awakened me last night when it had shone its light full on my face.

I slept. And . suddenly I was awake and in great fear, though for some seconds I did not know why. I was aware of a cold draught. I was lying on my back and my room was full of moonlight. But that was not all that was in my room. Someone was there . someone was standing at the foot of my bed watching me.

I think I called out, but I am not sure; I started up and then I felt as though all my limbs were frozen and for several seconds I was as one tamed to stone. If ever I had known fear in my life I knew it then.

It was because of what I saw at the foot of my bed . something which moved yet was not of this world.

It was a figure in a black cloak and cowl a monk; over the face was a mask such as those worn by torturers in the chambers of the Inquisition; there were slits in the mask for the eyes to look through, but it was not possible to see those eyes though I believed they watched me intently.

I had never before seen a ghost. I did not believe in ghosts. My practical Yorkshire soul rebelled against such fantasies. I had always said I should have to see to believe. Now I was seeing.

The figure moved as I looked. Then it was gone.

It could be no apparition, for I was not the sort of person to see apparitions. Someone had been in my room. I tamed to follow the figure but I could see nothing but a dark wall before my eyes. So dazed was I, so shocked, that it was a second or so before I realised that the curtain on one side of my bed had been drawn so that the door and that part of the room which led to it were shut off from my view.

Still numb with shock and terror I could not move until suddenly I thought I heard the sound of a door quietly closing. That brought me back to reality. Someone had come into my room and gone out by the door; ghosts, I had always heard, had no need to concern themselves with the opening and shutting of doors.

I stumbled out of bed, falling into the curtain which I hastily pushed aside. I hurried to the door, calling: “Who was that? Who was that?”

There was no sign of anyone in the corridor. I ran to the top of the stairs. The moonlight, falling through the windows there, threw shadows all about me. I felt suddenly alone with evil and I was terrified.

I began to shout: Come quickly. There is someone in the house. “

I heard a door open and shut; then Ruth’s voice:

” Catherine, is that you?”

” Yes, yes … come quickly….”

It seemed a long time before she appeared; then she came down the stairs wrapping a long robe about her, holding a small lamp in her hand.

“What happened?” she cried.

” There was something in my room. It came and stood at the bottom of my bed.”

” You have had a nightmare.”

” I was awake, I tell you. I was awake. I woke up and saw it. It must have wakened me.”

” My dear Catherine, you’re shivering. You should get back to bed. In your state …”

” It came into my room. It may come again.”

” My dear, it was only a bad dream.”

I felt frustrated and angry with her. It was the beginning of frustration, and what could be more exasperating than the inability to convince people that you have seen something with your eyes and not with your imagination?

” It was not a dream,” I said angrily. ” Of one thing I am certain, it was not a dream. There was someone in my room. I did not imagine it.”

Somewhere in the house a clock struck one, and almost immediately Luke appeared on the landing above us.

“What’s the commotion?” he asked, yawning.

” Catherine has been … upset.”

” There was someone in my room.”

” Burglars?”

” No, I don’t think so. It was someone dressed as a monk.”

” My dear,” said Ruth gently, ” you’ve been going to the Abbey and letting yourself get imaginative there. It’s an eerie place. Don’t go there again. It obviously upsets you.”

” I keep telling you that there was actually someone in my room. This person had drawn the curtain about my bed so that I shouldn’t see his departure.”

” Drawn the curtain about your bed? I expect Mary Jane did that.”

” She did not. I have told her not to. No, the person who was playing this joke—if it was a joke—drew it.”

I saw Ruth and Luke exchange glances, and I knew that they were thinking I was obsessed by the Abbey; clearly I was the victim of one of those vivid nightmares which hang about when one wakes and seem a part of reality.

” It was not a dream,” I insisted fervently. ” Someone came into my room. Perhaps it was meant to be a joke …”

I looked from Ruth to Luke; would either of them play such a stupid trick? Who else could have done it? Sir Matthew? Aunt Sarah? The apparition which had flitted across my room, quietly closing the door after it, must have been agile.

” You should go back to bed,” said Ruth. ” You should not let a nightmare disturb you.”

Go back to bed. Try to sleep. Perhaps to be awakened by that figure at the bottom of my bed! It had merely stood there this time and looked at me. What would it do next? How could I sleep peacefully again in that room?

Luke yawned. Clearly he thought it strange that I should wake them because of a dream.

“Come along,” said Ruth gently and, as she slipped her arm through mine, I remembered that I was in my night dress and presented an unconventional sight to the pair of them.

Luke said: ” Good night,” and went back to his room, so that I was left alone with Ruth.

” My dear Catherine,” she said as she drew me along the corridor, ” you really are scared.”

“It was … horrible. To think of being watched while I was asleep, like that.”

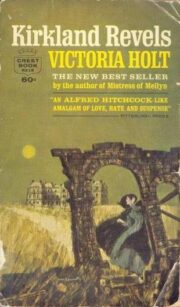

"Kirkland Revels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Kirkland Revels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Kirkland Revels" друзьям в соцсетях.