It was only a few days later when it was discovered that the warming-pan was missing from my room.

I had not noticed that it was gone, so could not say exactly how long it had been absent from its place on the wall over the oak chest in my bedroom.

I was sitting up in bed while Mary-Jane brought my breakfast-tray to me. I had taken to having breakfast in bed on Dr. Smith’s orders, and I must say that I was ready enough to indulge myself in this way, because, on account of the disturbed nights I was having, I almost invariably felt delicate in the mornings.

“Why, Mary-Jane,” I said, my eyes straying to the wall, “what have you done with the warming-pan?”

Mary-Jane set down my tray and looked round. Her astonishment was obvious.

” Oh, madam,” she said, ‘” it’s gone.”

” Did it fall or something?”

” That I couldn’t say, madam. I didn’t take it away.” She went over to the wall. ” The hook’s still there, any road.”

” Then I wonder who …” I’ll ask Mrs. Grantley. She might know what has happened to it. I rather liked it there. It was so bright and shining. “

I ate my breakfast without giving much thought to the warming-pan. At that stage I did not realise that it had any connection with the strange things which were happening to me.

It was that afternoon before I again thought of it. I was having tea with Ruth and she was talking about Christmas in the old days and how different it was now particularly this year when we were living so quietly on account of Gabriel’s death.

” It was rather fun,” she told me. ” We used to take a wagon out to bring the yule log home; and there was the holly to gather too. We usually had several people staying in the house at Christmas. This time it can’t possibly be more than family. I suppose Aunt Hagar will come over from Kelly Grange with Simon. They generally do, and stay two nights. She’s almost certain to manage that journey.”

I felt rather pleased at the prospect of Christmas, and wondered when I could go into Harrogate, Keighly or Ripon to buy some presents. It seemed incredible that it was only last Christmas when I was in Dijon.

Rather lonely those Christmases had been because most of my companions had gone home to their families and there were usually no more than four or five of us who remained at the school. But we had made the most of the festivities and those Christmases had been enjoyable.

” I must find out if Aunt Hagar will be able to make the journey. I must tell them to air her bed thoroughly; last time she declared we were putting her into damp sheets.”

That reminded me.

“By the way,” I said, “what has happened to the warming-pan which was in my room?”

She looked puzzled.

” It’s no longer there,” I explained. ” Mary-Jane doesn’t know what has become of it.”

” Warming-pan in your room? Oh … has it gone?”

” So you didn’t know. I thought perhaps you’d given orders for someone to remove it.” She shook her head. ” It must have been one of the servants,” she said. ” I’ll find out. You may be needing it when the weather turns, and we can’t expect this mildness to continue long now.”

” Thanks,” I answered. ” I’m thinking of going into Harrogate or Ripon soon. I have some shopping to do.”

” We might all go together. I want to go, and Luke was saying something about taking Damaris in to do some Christmas shopping.”

” Do let us. I should enjoy that.”

Next day I met her on the stairs, when I was on the point of going out for a short walk because the rain had ceased for a while and the sun was shining.

” Going for a walk?” she asked. ” It’s pleasant out. Quite warm. By the way, I cannot discover what happened to yom warming-pan.”

” Well that’s strange.”

” I expect someone moved it and forgot.” She gave a light laugh and looked at me somewhat intently, I thought. But I went out and it was such a lovely morning that I immediately forgot all about the missing warming-pan. There were still a few flowers left in the hedgerows such as woundwort and shepherd’s purse, and although I did not go to the moor I thought I saw in the distance a spray of gorse, golden in the pale sunshine.

Remembering instructions, I curtailed my walk, and as I turned back to the house I glanced towards the ruins. It seemed quite a long time since I had been to the Abbey. I knew I could never go there now without remembering the monk, so I stayed away, which showed, of course, that my protestations of bravery were partly false.

I stood under an oak tree and found myself studying the patterns on the bark. I remembered my father’s telling me that the ancient Britons used to think that marks on the trunk of the oak were the outward signs of the supernatural being who inhabited the tree. I traced the pattern with my finger. it was easy to understand how such fancies had grown.

It was so easy to harbour fancies.

As I stood there I heard a sudden mocking cry above me, and looked up startled, expecting something terrifying. It was only a green woodpecker.

I hurried into the house.

When I went to the dining-room that evening for dinner I found Matthew, Sarah and Luke there; but Ruth was absent.

When I entered they were asking where she was.

” Not like her to be late,” said Sir Matthew.

” Ruth has a great deal to do,” Sarah put in. ” And she was talking about Christmas and wondering which rooms Hagar and Simon would want if they came for a short holiday.”

” Hagar will have the room which was once hers,” said Matthew. ” Simon will have the one he has always had. So why should she be concerned?”

“I think she’s a little worried about Hagar. You know what Hagar is.

She’ll have her old nose into every corner and be telling us that the place is not kept as it was when Father was alive. “

” Hagar’s an interfering busybody and always was,” growled Matthew. “

If she doesn’t like what she sees here, then she can do the other thing. We can manage very well without her opinions and advice.”

Ruth came in then, looking slightly flushed.

” We’ve been wondering what had become of you,” Matthew told her.

” Of all the ridiculous things …” she began. She looked round, the company helplessly.

“I went into … Gabriel’s room and noticed something under the coverlet there. What do you think it was?”

I stared at her and felt the colour rushing to my cheeks, and I was fighting hard to control my feelings, because I knew.

“The warming-pan from your room!” She was looking straight at me, quizzically and intent. ” Whoever could have put it there?”

“How extraordinary!” I heard myself stammer.

” Well, we’ve found it. That’s where it was all the time.” She turned to the others. ” Catherine had missed the warming- pan from her room.

She thought I’d told one of the servants to remove it. Who on earth could have put it into the bed there? “

” We ought to find out,” I said sharply.

“I asked the servants. They quite clearly knew nothing about it.”

” Someone must have put it there.” I heard my voice rise unnaturally high.

Ruth shrugged her shoulders.

” But we must find out,” I insisted.

“It’s someone playing these tricks. Don’t you see … it’s the same sort of thing as the curtains being drawn.”

” Curtains?”

I was annoyed with myself because the drawing of the bed curtains had been a matter known only to the one who had done it, and Mary-Jane and myself. Now I should have to explain. I did so briefly.

” Who drew the curtains?” screeched Sarah. ” Who put the warming-pan in Gabriel’s bed? And it was your bed, too, wasn’t it, Catherine.

Yours and Gabriel’s. “

” I wish I knew!” I cried vehemently.

“Someone must have been rather absent-minded,” said Luke lightly.

“I don’t think it was absent-mindedness,” I retorted.

“But, Catherine,” put in Ruth patiently, “why should anyone want to pull your bed curtains about your bed or remove the warming-pan?”

” That’s what / should like to know.”

“Let’s forget all about it.” said Matthew.

“That which was lost is found.”

” But why … why …?” I insisted.

” You are getting excited, my dear,” whispered Ruth.

“I want to know the explanation of these strange things which are happening in my room.”

“The duckling is getting cold,” said Sir Matthew. He came to me and slipped his arm through mine. ” Never mind about the warming-pan, my dear. We shall know why it was moved … all in good time.”

” Yes,” said Luke, ” all in good time.” And he kept his eyes on my face as he spoke, and I could see the speculation there.

“We’d better start,” said Ruth, and as they sat down at the table I had no alternative but to do the same; but my appetite had deserted me. I kept asking myself what the purpose was behind these strange happenings which seemed in some way to be directed towards me.

I was going to find out. I must find out.

Before the month was out we were invited to the vicarage to discuss the last-minute plans for the imminent ” Bring and Buy Sale.”

” Mrs. Cartwright always gets the wind in her tail at such times,” said Luke. ” This is nothing to the June garden fete or her hideous pa gents

” Mrs. Cartwright is an energetic lady,” said Ruth, ” possessing all the qualities to make her an excellent wife for the vicar.”

” Does she expect me to go?” I asked.

” Of course she does. She’d be hurt if you didn’t. You will come?

It’s only a short walk, but if you like we can drive there.”

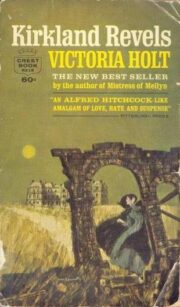

"Kirkland Revels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Kirkland Revels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Kirkland Revels" друзьям в соцсетях.