But the child was there, reminding me of its existence. Where I went there must the child go; what happened to me must have its effect on the child. I was going to fight this thing which was threatening to destroy me—not only for myself but for the sake of one who was more precious to me.

When Mary-Jane came in with my breakfast she did not see that anything was different, and I felt that was my first triumph. I had been terrified that I should be unable to hide the fear which had almost prostrated me on the previous day ” It’s a grand morning, madam,” she said.

” Is it, Mary Jane

” A bit of a wind still, but any road t’sun’s shining.”

” I’m glad.”

I half closed my eyes and she went out. I found it difficult to eat, but I managed a little. The sun sent a feeble ray on to the bed and it cheered me; I thought it was symbolic. The sun is always there, I reminded myself, only the clouds get in between. There’s always a way of dealing with every problem, only ignorance gets in the way.

I wanted to think very clearly. I knew in my heart that what I had seen had been with my eyes, not with my imagination. Inscrutable as it seemed, there was an explanation somewhere.

Damaris was clearly involved in the plot against me; and what more reasonable than that she should be, for if Luke wished to frighten me into giving birth to a stillborn child, and Damaris was to be his wife, it was surely reasonable enough to suppose that she would work with him.

But it was possible that these two young people could plot so diabolical a murder, for murder it would be even though the child had not come into the world.

I tried to review the situation clearly and work out what must be done.

The first thing that occurred to me was that I might go back to my father’s house. I rejected that idea almost as soon as it came. I should have to give a reason- l should have to say: ” Someone at the Revels is trying to drive me to the brink of madness. Therefore I am running away.” I felt that it Would be an admission of my fear, and if, for one moment, I accepted the view that I was suffering from hallucinations, I had taken the first steps on that road along which someone here was trying to force me.

I did not think at this time I could endure the solemnity, the morbid atmosphere of my father’s house.

I had made my decision: I could never know peace of mind again until I had solved this mystery. It was therefore not something from which I could run away. I was going to intensify my search for my persecutor.

I owed it to myself and to my child.

I must now make a practical plan, and I decided that I would go to Hagar and take her into my confidence. I should have preferred to act alone, but that was impossible because my first step, I had decided, must be to go to Worstwhistle and confirm Dr. Smith’s words.

I could not ask anyone at the Revels to drive me there so I must go to Hagar. | When I had bathed and dressed I set out immediately for |

Kelly Grange. It was about half past ten when I arrived, and I went straight to Hagar and told her what the doctor had told me.

She listened gravely and when I had finished she said:

Simon shall take you to that place immediately. I think with you that should be the first step. “

She rang for Dawson and told her to send Simon to us at once.

Remembering my suspicions of Simon I was a little anxious, but I realised that I had to get to Worstwhistle even if it did mean taking a chance; and as soon as he entered the room my suspicions vanished, and I was ashamed that I had ever entertained them. That was the effect he was beginning to have on me.

Hagar told him what had happened. He looked astonished and then he said: ” Well, we’d better get over to Worstwhistle right away.”

” I will send someone over to the Revels to tell them that you are taking luncheon with me,” said Hagar; and I was glad she had thought of that because I should have aroused their curiosity if I had not returned.

Fifteen minutes later Simon was driving the trap, with me sitting beside him, along the road to Worstwhistle. We did not speak much during that journey; and I was grateful to him for falling in with my mood. I could think of nothing but the interview before me which was going to mean so much to me. I kept remembering my father’s absences from home and the sadness which always seemed to surround him; and I could not help believing that there was truth in what the doctor had told me.

It was about midday when we came to Worstwhistle a grey stone building which to my mind resembled nothing so much as a prison. It was a prison, I told myself stone walls within which the afflicted lived out their clouded lives. Was it possible that my own mother was among those sad in habitants, and that there was a plot afoot to make me a prisoner here?

I was determined that should never be.

Surrounding the building was a high wall and when we drew up at the heavy wrought-iron gates, a porter came out of the lodge and asked our business.

Simon told him authoritatively that he wished to see the Principal of the establishment.

“You have an appointment with him, sir?”

” It’s of the utmost importance,” Simon replied and threw the man a coin.

Whether it was the money or Simon’s manner, I was not sure, but the gates were opened to us and we drove along a gravel drive to the main building.

A man in livery emerged as we approached and Simon dismounted and helped me down.

” Who’ll hold the horse?” he asked.

The porter shouted and a boy appeared. He held the horse while we, with the man in livery, went towards the porch.

” Will you tell the Principal that we wish to see him immediately on a matter of great urgency?”

Again I was grateful for that authoritative arrogance which resulted in immediate obedience.

We were led through the porch into a stone-flagged hall in which a fire was burning; but it was not enough to warm the place, and I felt the chill. But perhaps it was a spiritual rather than a physical chill.

I was shivering. Simon must have noticed this for he took my arm and I found comfort in that gesture.

” Please to sit in here, sir,” said the porter; and he opened a door on our right to disclose a high-ceilinged room with whitewashed walls, a heavy table, and a few chairs.

“Your name, sir?”

” This is Mrs. Rookwell of Kirkland Revels, and I am Mr. Redvers.”

” You say you had an appointment, sir?” '

” I did not say so.”

” It’s usual to make one, sir.”

” We are pressed for time and, as I said, the matter is urgent. Pray go and tell the Principal that we are here.”

The porter retired, and when he was gone Simon smiled at me.

” Anyone would think we were trying to see the Queen.” Then his face softened into a tenderness which I had never seen him give to anyone before except perhaps Hagar. ” Cheer up,” he said, ” even if it’s true, it’s not the end of the world, you know.”

” I’m glad you came with me, I hadn’t meant to say that but the words slipped out.

He took my hand and pressed it firmly. It was a gesture which meant that we were not foolish, hysterical people and should be able to take the calm view.

I walked away from him because I did not trust my emotions. I went to the window and looked out, and I thought of the people who were held captive here. This was their little world. They looked out on the gardens and the moor beyond if they were allowed to look out of windows and this was all they knew of life. Some had been here for years . seventeen years. But perhaps they were kept shut away.

Perhaps they did not even see the gardens and the moor.

It seemed that we waited a very long time before the porter returned.

Then he said: ” Come this way, will you, please.”

As we followed him up a flight of stairs, and along a corridor, I caught a glimpse of barred windows and shivered. So like a prison, I thought.

Then the porter rapped on a door on which the word ” Superintendent” had been painted. A voice said ” Come in” ; and Simon, taking my arm, drew me into the room with him. The whitewashed walls were bare; the oilcloth polished to danger point; and it was a cold and cheerless room; at a desk a man with a tired grey face and a resentful look in his eyes because, I presumed, we had dared invade his privacy without an appointment.

” Pray sit down,” he said, when the porter had left us. ” Am I to understand that your business is urgent?”

” It is of the utmost urgency to us,” said Simon. I spoke then. ” It was good of you to see us. I am Mrs. Rockwell, but before my marriage I was Catherine Corder.”

” Oh!” The gleam of understanding which came into hu face was a blow which shattered my hopes. I said: “You have a patient here of that name?”

” Yes, that is so.”

I looked at Simon and, try as I might, I could not speak because my tongue had become parched, my throat constricted

” The point is,” went on Simon, ” Mrs. Rockwell has only very recently heard that a Catherine Corder may be here. She has reason to believe that this may be her mother. She has always been under the impression that her mother died when she was very young. Naturally she wishes to know whether the Catherine Corder in this establishment is her mother.”

” The information we have about our patients is confidential as you will appreciate.”

” We do appreciate that,” said Simon. ” But in the case of very close relatives would you not be prepared to give the information which was asked?”

” It would first be necessary to prove the relationship.” I burst out:

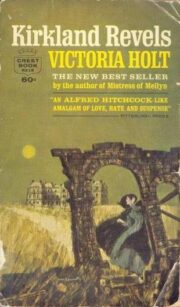

"Kirkland Revels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Kirkland Revels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Kirkland Revels" друзьям в соцсетях.