“Really,” she said.

“What do you want?” he asked.

It would’ve been too easy—and too cheesy—to say “you,” even if it was top-of-mind right at the moment.

“I want to write,” Georgie said. “I want to make people laugh. I want to create a show. And then another show. And then another show. I want to be James L. Brooks.”

“I have no idea who that is.”

“Philistine.”

“He’s a philistine?”

“And I want to write a book of essays. And I want to join The Kids in the Hall.”

“You’ll have to pretend you’re a man,” Neal said.

“And a Canadian,” she agreed.

“And you’ll have to do lots of sketches where you’re in drag as a man, in drag as a woman—it’ll be very confusing.”

“I’m up for it.”

Neal laughed. (Almost. He smiled, and his shoulders and chest twitched.)

“And I want a Crayola Caddy,” Georgie said.

“What’s a Crayola Caddy?”

“It’s this thing they made when we were kids, kind of a lazy Susan with crayons and markers and paints.”

“I think I had one of those.”

Georgie yanked on his hand. “You had a Crayola Caddy?”

“I think so. It was yellow, right? And it came with poster paints? I think it’s still in our basement.”

“I’ve wanted a Crayola Caddy since 1981,” Georgie said. “It’s all I asked Santa Claus for, three years in a row.”

“Why didn’t your parents just buy it for you?”

She rolled her eyes. “My mom thought it was stupid. She bought me crayons and paint instead.”

“Well”—he lowered his eyebrows thoughtfully—“you could probably have mine.”

Georgie punched his chest with their clasped hands. “Shut. Up.” She knew it was stupid, but she was genuinely thrilled about this. “Neal Grafton, you have just made my oldest dream come true.”

Neal held her hand to his heart. His face was neutral, but his eyes were dancing. He whispered: “What else do you want, Georgie?”

“Two kids,” she said. “A boy and a girl. But not until my TV empire is under way.”

His eyes got big. “Christ.”

“Also a house with a big front porch. And a husband who likes to take driving vacations. And a car, obviously, with a roomy backseat.”

“You really are spectacular at this.”

“And I want a Disneyland annual pass. And a chance to work with Bernadette Peters. And I want to be happy. Like, seventy to eighty percent of the time. I want to be actively, thoughtfully happy.”

Neal was rubbing their hands into his blue sweatshirt. It said NORTH HIGH WRESTLING. TAKE ’EM DOWN, VIKES! His jaw was tight, and his blue eyes were almost black.

“And I want to fly over the ocean,” she said.

He swallowed and reached out to touch her face with his free hand. It was cold, and sand fell from it onto Georgie’s neck. “I think I want you,” he said.

Georgie squeezed the hand he was holding to his chest, and used it as an anchor to pull herself closer. “You think . . .”

Neal licked his bottom lip and nodded. “I think . . .” The closer she was, the more he looked away. “I think I just want you,” he said.

“Okay,” Georgie agreed.

Neal looked surprised—he almost laughed. “Okay?”

She nodded, close enough to bump her nose up against his. “Okay. You can have me.”

He pushed his forehead into hers, pulling his chin and mouth back. “Just like that.”

“Yeah.”

“Really,” he said.

“Really,” she promised.

She reached her mouth toward his, and he twisted his head up and away, looking at her. He was breathing hard through his nose. He was still holding her cheek.

Georgie tried to make her face as plain as possible:

Really. You can have me. Because I’m good at wanting things and good at getting what I want, and I can’t think of anything I want more than you. Really, really, really.

Neal nodded. Like he’d just been given an order. Then he let go of Georgie’s hand and pushed her (pinned her) gently (firmly) back into the sand.

He leaned over her, his hands on either side of her shoulders, and shook his head. “Georgie,” he said. Then he kissed her.

That was it, really.

That was when she added Neal to the list of things she wanted and needed and was bound to have someday. That’s when she decided that Neal was the person who was going to drive on those overnight road trips. And Neal was the one who was going to sit next to her at the Emmys.

He kissed her like he was drawing a perfectly straight line.

He kissed her in India ink.

That’s when Georgie decided, during that cocksure kiss, that Neal was what she needed to be happy.

They were all tired.

Seth had finger-combed all the curl out his hair. It was looking less JFK Jr., more Joe Piscopo. “We’re not adding a gay Indian character,” he said. That’s final.”

Scotty leaned over the table. “But Georgie said she wanted to add some diversity.”

“She didn’t say she wanted to add you.”

“Rahul isn’t me. He’s tall, and he doesn’t wear glasses.”

“He’s worse than you,” Seth said. “He’s fantasy-you.”

“Well, all these white guys are just fantasy-yous.”

Seth abused his hair some more. “Fantasy-me would never show up on this show. Fantasy-me was already on Gossip Girl.”

“Georgie,” they both said at once.

“Rahul can stay,” Georgie said. “But this is a misfit comedy; he has to be short and wear glasses.”

“Why would you do that to Rahul?” Scotty folded his arms. “Now he’ll never find love.”

Seth rolled his eyes. “Jesus, Scotty, you’ll find love.”

“One, I’m talking about Rahul. And two, I don’t think you mean that.”

Georgie put her hand on Scotty’s shoulder. “He’ll find love, Scotty. I’ll write him a dreamy boyfriend.”

“You’d do that for me, Georgie?”

“I’ll do it for Rahul.”

“That episode better be fucking hilarious,” Seth said.

Scotty stood up and shoved his laptop in his backpack. “Rahul stays,” he told Seth. “I just made some Indian kid a star.”

Scotty walked out, head high.

Seth was still frowning. “Does this mean we have to go back and write Rahul into the pilot?”

“He can start in the third episode,” Georgie said. “You were just saying we needed a couple gay characters. You said our 1995 was showing.”

“I know.”

Georgie closed her laptop. “I know we said we’d take home scripts, but I don’t know how much I’m going to get done tonight. . . .”

“Stay,” Seth said. “We’ll get dinner and work on it together.”

“I can’t. I have to call Neal.” It was already eight o’clock in Omaha. Georgie wanted to call him by ten.

Seth studied her for a minute. Like the one thing she wasn’t telling him was the only thing he didn’t know about her.

What would happen if she called Seth tonight from the yellow phone? Would she get the Sig Ep house in 1998? Would one of his Saturday-morning girls answer?

Seth never talked about the Saturday-morning girls now, but Georgie assumed the parade marched on.

“Thanks,” he said. “For pushing through today. I know that something is seriously fucked up with you.”

Georgie unplugged her phone.

“And it’s killing me that you won’t talk about it,” he said.

“I’m sorry.”

“I don’t want you to be sorry, Georgie—I want you to be funny.”

CHAPTER 17

By the time Georgie pulled into her mom’s driveway, she was 100 percent sure that if she called Neal tonight from the yellow rotary phone, he’d pick it up in the past.

Or that it would seem that way—that the grand illusion was going to hold.

And she was 1,000 percent sure she was going to call him. Even though that might be dangerous. (If it were real.) (Georgie needed to pick a side—real or not real—and stick with it.)

She had to call. You can’t just ignore a phone that calls into the past. You can’t know it’s there and not call.

Georgie couldn’t, anyway.

Whatever was happening, this was the role she’d been given. Neal wasn’t the one with a magic phone that could call into the future.

(God, maybe she should test that theory, she could ask him to call her back . . . No. No way. What if her mom answered and started talking about Alice and Noomi and divorce? What if Georgie herself answered the phone back in 1998 and said something horrible and immature, and ruined everything? Nineteen-ninety-eight Georgie clearly couldn’t be trusted.)

Heather opened the door to the house before Georgie could knock.

“Is there a pizza coming?” Georgie asked.

“No.”

Georgie stayed out on the stoop.

“Baked ziti,” Heather said, rolling her eyes. “Just come in.”

Georgie did. Her mom and Kendrick were eating dinner in the kitchen.

“You’re home early,” her mom said. “I made a Caesar salad, if you’re hungry, and there’s puppy chow for dessert.”

The pugs started barking under the table.

“Not for you, little mama,” Georgie’s mom said, leaning over to make eye contact with the pregnant one. “This puppy chow is for big mamas and daddies. Little mamas can’t have chocolate—I swear, Kenny, they understand everything we say.”

Heather was standing to the side of the front door, pulling out the curtain, so she could peek out at an angle.

They were all completely over the fact that Georgie was here. Even the dogs had stopped tracking her every movement with their little whiteless eyes.

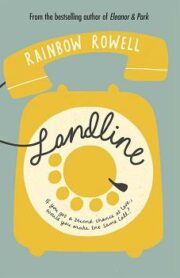

"Landline" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Landline". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Landline" друзьям в соцсетях.