She nodded silently and started up the steps. Shawn reached for her hand, but she sprinted out of reach, up the stairs.

"I’ll call you," he said, his usual bravado returning.

She didn’t answer, just ran into the house and closed the door.

As she sat at her dressing table she untied her neck scarf and stared dully at her image in the mirror. Wrinkling her nose, she whispered, "What a mess you’ve made of things! You sat home last night, hoping Joe would call, and tonight you’ll sit home alone because you sent Shawn away." Maybe Sarah was right. It was time for a decision. Who was it to be? Shawn or Joe?

The next few days she threw herself into her studies and her suffragist meetings. Time went quickly, and it wasn’t long before she and Shawn were back on their usual footing. He had called her every night, and he was so sweet that it wasn’t hard to forgive him.

Saturday they went on a canal-boat ride pulled by mules all the way to Lock Five. She had packed a lunch, and the afternoon was most pleasant. Still, at times, the encounter between Joe and Shawn haunted her, and she wished Shawn weren’t so possessive and that Joe was more so.

Joe would be home in October — then perhaps she would make a decision. She certainly couldn’t have Joe and Shawn embroiled in another fight over her. Maybe she shouldn’t see Joe anymore. She probably shouldn’t see Shawn, either, at least not for a while, but he was irresistible, always attentive, clever, funny, and yes, even lovable.

Sarah was right — she shouldn’t play the field and pit her two beaux against one another. She must straighten out this situation — and soon. This, she promised she would do, for it was only fair to Shawn and Joe.

Chapter Twenty-four

The influenza epidemic had hit Boston, with over five-hundred deaths reported. By law Bostonians could only venture outside if they were wearing a face mask. But New York was one of the hardest hit cities in the country, with almost twenty-five thousand registered deaths.

By the first part of October there were over seven hundred flu cases reported in Washington. No one, however, least of all President Wilson, seemed too alarmed. In fact, the president had a little limerick he recited about the flu:

I had a little bird

Its name was Enza,

I opened the window

And in-flu-enza.

Laura wasn’t too concerned about the flu, either, as she sat in English class, ready to give her recitation on Emmeline Pankhurst. She was well prepared and spoke clearly and firmly.

When Laura finished and gathered up her notes, she was greeted with a round of applause. Even Olaf Jorgensen beat his large hands together in approval.

"That was terrific, Laura," he whispered after she was seated. His ruddy, large face was beaming.

Laura was pleased also. After class she was delighted to learn that Miss Foster had given her an A+.

Walking home, she felt the brisk air enlivening her step. The pin oak, red oak, and silver maples were beginning to change to new autumn colors, and she spied a yellow finch darting from one tree to another.

Fall was her favorite time of year. She loved the tangy air, the red and yellow fall leaves, and the brisk breeze from the north. She smiled when she thought of Washington’s nickname — "the green-and-white city" — because of all the trees with white buildings nestled in between. In the autumn, however, the city didn’t live up to the name, for the trees took on too many vibrant hues.

She was happy about life, too. Shawn was beginning to listen to her and recently had said nothing derogatory about the suffragists. Perhaps she was making a difference in his attitude after all. She did long for the old casual footing she had with Joe, but that seemed to have disintegrated even before his confrontation with Shawn. Maybe when he came home on October twenty-second, things would be different. But even as the thought flickered through her mind, she was afraid it was only wishful thinking. She’d been doing too much wishful thinking lately. Joe seemed bent on stepping aside for Shawn, and perhaps he was right. Her mother had tried to steer her to Joe, but now she was the one that needed to make a choice. The old frustrated feelings welled up inside, closing her throat. What should she do?

She patted her knapsack bulging with note cards. Because of her neat handwriting, Lucy Burns asked her to recopy fifty cards for the index. She had agreed but would much rather have been the one to be calling the senators or what the newspaper called "tele-suffing." Although all the suffragists had received a "Don’t List" on how to talk to a senator, it didn’t do her any good. She was too young. She remembered some of the "Don’ts" on the list that each new interviewer was given, though, such as:

Don't nag.

Don't boast.

Don't threaten.

Don't lose your temper.

Don't stay too long.

She sighed. It was always her age that stood in the way. A person-to-person interview with a senator she could understand, but why couldn’t she call? She could crank the phone, give the operator the number, and talk pleasantly to a senator just as well as the older women.

Dashing up the steps, she took the mail from the box and unlocked the door. As she sifted through the mail — the Ladies Home Journal, an advertisement for a shampoo — she noticed that her mother and Sarah were gone. Her heart lurched when she saw a letter from Michael; at least his name was on the return address. But it wasn’t his handwriting. She shed her long, loose vest and tore open the envelope. Something must be wrong!

Hastily she scanned the contents:

Field Hospital

Near Paris

September 15, 1918

Dear Mom, Laura, and Sarah,

Here I am in a field hospital about fifteen miles northwest of Paris. There’s nothing to be alarmed about. I landed here because my shoulder caught a piece of German shrapnel — it’s a souvenir from our offensive attack on Saint-Mihiel. As you can see, this isn’t my handwriting. I dictated this letter to one of the prettiest French nurses you’ve ever seen. Her name is Françoise Giraud and she reminds me of you, Laura, except she has raven-black hair.

Before we began the attack, the German line was bombarded for four hours and the U.S. Gas Regiment gave our troops a smoke screen. The 42nd Division had only a few casualties. Wouldn’t you know I had to be one of them!

We easily took Saint-Mihiel. Next we’re to open an offensive in the Meuse-Argonne, a sector sixty miles west of here, but I’m stuck here with a beautiful nurse instead! War is hell!

We did ourselves proud at Saint-Mihiel. Even Premier Clemenceau and the president of France, Poincaré, came to the front to offer their congratulations.

Well, Françoise needs to make her rounds, so I’d better quit for now.

Don’t worry. I’m getting lots of tender loving care. I don’t know when I’ll be sent home, but it shouldn’t be too long before my medical discharge comes through.

As the song says, "Keep the Home Fires Burning."

All my love,

Mike

Dropping the letter in her lap, Laura stared at the grandfather clock with its gilt Roman numerals, but even when the chimes rang, the time didn’t register. She was thinking of Michael, who had helped shape her ideas and taught her, as her father had done, to stand firm in her beliefs as long as they didn’t hurt people. How much fun she had growing up with Michael! The memory of their fishing expeditions on the Potomac, where they fished for brook trout, came flooding back. Smiling wistfully, she remembered how Mike had allowed her to wear his old knickers and vest and how she had tucked her mass of hair beneath one of his large caps. With a pole balanced on her shoulder she marched proudly by his side.

Her eyes brimmed with tears when she thought of how things had changed. Mike was lying wounded in France, and she was involved in other interests. Becoming an adult was often filled with loss and pain. She sighed. There was little chance they would ever recapture those carefree fishing days.

She propped the letter on the hall table where her mother and Sarah would be certain to see it. With a sad weariness she went up to her room to work on the note cards.

In the next few weeks Laura was involved in the Banner Campaign, which consisted of picketing the Senate and especially the thirty-four senators who had voted against the amendment.

On Saturday she, along with Cassie and other suffragists, marched to the Capitol.

She glanced at Cassie, feeling a deep commitment to her country and the women with whom she marched. The impressive white dome with its many columns representing states of the union and the Goodness of Freedom crowning the cupola all made her tingle with pride.

They mounted the steps with the banner held between, each girl holding a wooden support. The columns surrounding them and the marble entrance were splendors Laura had forgotten. Perhaps she should return to her dream of becoming an architect.

Quietly she and Cassie stood atop the steps as men and women passed, some stopping to read their banner and others pointedly ignoring them. Dressed in her wine-colored suit, Cassie was the epitome of grace, while Laura, in the bulky navy sweater and skirt, made quite a contrast. Still, their yellow sashes indicated they were of one mind!

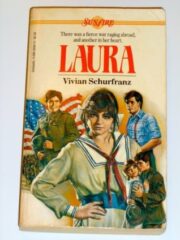

"Laura" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Laura". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Laura" друзьям в соцсетях.