Robert’s seed of an idea of an act with challenging people to ride Sea had developed into a comical routine. Firstly I was to ride Bluebell around the ring, vaulting on and off and then dancing on her back. I had yet to learn to jump through the hoop but I managed a couple of flat-footed jumps and a couple of skips.

‘Straighten up!’ Robert yelled at me time after time as I went bow-legged with my bottom stuck out backwards trying to keep my balance.

Straightening my legs on horseback was an act of pure will, I found. It was no easier in the ungainly crouch which came natural to me. I was probably making it harder for myself. But I found it such a relief to be within grabbing distance of the skewbald mane. Then:

‘Straighten up!’ Robert would yell again, and I would force myself to stand tall and even to look straight ahead with my chin up instead of gazing longingly at Bluebell’s broad back.

The act we planned would have me skipping and then jumping through an open hoop on Bluebell’s back. Then Jack, dressed in fustian breeches and gaiters, would come out from the back of the crowd like a drunken young farmer and demand a turn. At first I was supposed to refuse and turn my head away from him, at which Jack was to take a run from the far side of the ring and vault on to my place, pushing me off the other side.

Often we cracked heads, occasionally we would bounce off each other and fall back, off our own sides. Bluebell was excellent and stood as steady as a rock, even when Jack went up and I failed to drop off and we clung to each other and howled with exhausted laughter.

Then I was supposed to try to carry on with my act while Jack vaulted on to the horse. As long as I stayed well towards the tail and out of the way we were in little danger of collision. Jack vaulted on and ended up facing the tail, then he spun himself around so that he was facing the head, but both his legs were the same side. Then he lay flat on his back, his legs and arms on either side of the cantering horse. Then he spun around like a sack of meal. In the finale he crawled all around under Bluebell’s belly and then under her neck.

We practised it so often that we grew skilled and quick at it but it did not seem funny to us. We only realized how good it would be in the show when Dandy and Katie finished their practice early one day and came over to watch us, and actually collapsed on to the grass they were laughing so loud.

Robert, who had stood in the centre of the field for day after frozen day, had looked very thoughtful at that and had wandered off chewing on the stem of his pipe muttering to himself: ‘Lady and the Jester, the Girl and the Tramp, the Clowns on Horseback.’

Next day he had a sign-writer up and spent a long time with him in the stable yard while I worked the team of ponies in the paddock and Jack and Dandy and Katie practised in the barn.

The horse acts had grown almost beyond recognition now that I could ride in the ring and we had two rosinbacks. I did not yet know what order Robert planned to run the show but we had the dancing pony team, Snow doing his tricks with counting numbers and flags, Jack and me doing a two-horse bareback riding act, my dancing on the back of Bluebell, and then the second part of the act when Jack came in dressed as the farmer. The little ponies could still do the Battle of Blenheim of course; and it was rather more impressive now that the flower of British cavalry outnumbered the French by four to three, and for the end of the show Robert planned some kind of historical tableau.

‘Summat like Saladin, but with the three lasses,’ he said to himself, chomping on his pipe as he did when he was struggling with an idea. He walked around the stable yard in a small half-circle. The pipe puffed a little cloud of triumph. ‘Rape of the Sabine Women,’ he said to himself.

We would be an impressive sight on the road, too. There was Snow, Robert’s grey stallion; Sea, my grey stallion; Bluebell and Morris, the two rosinbacks; Lofty, the new wagon horse; and seven little ponies. Lofty was a heavy draught horse bought with Robert’s profits from the Salisbury gamble to pull the new wagon which would carry the heavy flying rigging and the new screens he ordered. Bluebell and Morris would pull the two sleeping wagons. This summer William would come on the road too, for the first time. Robert might be parsimonious but even he could see that Jack and he could not set the rigging alone. We would need help with the horses at the end of two shows as well.

Then we worked. Worked and waited. It snowed hard in January and when I fell off the back of Bluebell I fell soft into drifts on either side of my track. I fell wet and cold too and Robert took pity on me and ordered me two new pairs of breeches and smocks so that I could change into dry clothes at each break. Mrs Greaves kept them warming for me on the front of her stove and I would dash into the kitchen, my teeth chattering with the cold and strip off my icy cold breeches and smock and drop them on the floor.

William came in one time, as I stripped from my snow-encrusted smock, and dropped the pallet of wood he was carrying and had a tongue-lashing from Mrs Greaves and was banned from the kitchen. But then she turned to me.

‘You must cover yourself, Merry,’ she said gently. ‘You’re not a little girl any more.’

She reached behind the dresser and pulled out a big looking glass, at least a foot square. She held it up for me to see myself, and I craned my neck trying to see all of me in the one glass. I had shot up in height, I was nearly full grown and I had fattened up at last, I was no longer wiry and scrawny. I had filled out. The curves of my body were usually hidden by my smock or by the cut-down shirts of Jack’s I wore for work. Now, in my chemise I could see that my breasts had grown. I had a shadow of hair in each armpit and at my groin. My buttocks were smooth and as tightly muscled as a racehorse. My legs were long and lean, bruised like a charity schoolboy. I took a step closer to the mirror and looked at my face.

The hair I had hacked off in the summer had regrown and now fell to my shoulders in thick copper waves. The tumbling colour of it softened the hungry hard lines of my face and when I smiled the reflection which I saw was that of a stranger. My eyes seemed to have grown more green this winter, they were still set slanty as a cat, black-lashed. My nose was slightly skewed from the fall from the trapeze, my face would never be perfect. I would never have Dandy’s simple rounded loveliness.

‘You will be a great beauty,’ Mrs Greaves said. She took the mirror gently from me and tucked it back. ‘I only hope it will bring you some joy.’

‘I don’t want beauty,’ I said, and though I was a young girl and not very wise I told her the truth. ‘I don’t want beauty and I don’t want a man,’ I said. ‘All I want is a place of my own and some gold under my mattress. And Dandy safe.’

Mrs Greaves chuckled and helped me tie the strings at my cuffs. ‘The only way for a lass like you to get that is to find yourself a man and hope he’s a rich one,’ she counselled. ‘You’ll like it well enough when you’re older.’

I shook my head but said nothing.

‘What about that sister of yours?’ she asked me. ‘She’s set her sights on Master Jack, hasn’t she? Small change she’ll get there.’

I looked warily at Mrs Greaves. She worked in silence at the dinner table, she cooked in silence in the kitchen. But she saw a good deal more than anyone might expect. I knew she was not in Robert’s confidence, but I feared what she might tell him.

‘Who says?’ I asked, cautious as a hedgerow brat.

Mrs Greaves chuckled. ‘Think I’m blind, child?’ she asked me. ‘My tea doesn’t have great lumps in the pot, yet night after night that poor lad has drunk down God knows what nonsense. Is it working for her?’

My face was guarded. ‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘I don’t know what you mean.’

I did know. And it was working. The love potion, or the boredom of the short winter days and the long winter evenings. The flattery of two pretty girls or the importance of being their catcher. Something was calling Jack over to our little room above the stable for evening after evening while his father pored over maps and over almanacs of fairs.

We would hear his step on the foot of the stair and then his low: ‘Hulloa!’ and Dandy would call back: ‘Come up, Jack!’ in a voice of lazy sweetness.

She would toss a handful of lavender seeds on the fire so it smoked with an acrid sweetness. She would kick a pair of soiled clouts under the mattress, and she would loosen the top of her bodice so that it showed the creamy curves of the tops of her breasts. Then she would wink at Katie and me and say, ‘Ten minutes, mind,’ in quite a different voice to the two of us.

Night after night Jack’s head came through the trapdoor wearing his half-rueful, half-roguish smile.

‘Hello Meridon, Dandy, Katie,’ he would say. ‘I brought you some apples from the store room.’

He would hand them out and we would sit and munch the icy fruit and talk about the work we had done that day. The tricks that had worked or failed and our hopes for the season ahead of us.

After about ten minutes or so Katie, who had now seen the golden guinea she was to collect at Easter, would prompt me.

‘I’ll help you water-up, Merry,’ she would say; and the two of us would go down the stairs to check all the horses had water and hay for the night and that they were safe in the paddock. Snow and Sea were kept indoors and we would check them too. Sometimes we would idle then, in the loose-boxes, giving Dandy and Jack time to be alone together. I would half listen to Katie’s chatter about lads in Warminster and one time a real gentleman from as far away as Bath, but most of the time I would lean my cheek against Sea’s warm neck and wish we were far away.

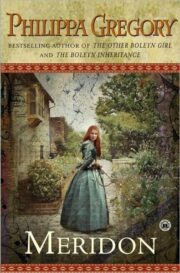

"Meridon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Meridon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Meridon" друзьям в соцсетях.