I thought it must be between seven and eight of the clock, but I could not be sure. It did not matter. If I was anxious to see the time there would be a village church with a steeple and a clock soon enough, even on this deserted road. I was not hungry. I was exhausted with fatigue but I did not crave sleep. It did not matter to me if this night was just begun, or half done, or if it never ended at all. I slouched in the saddle and let Sea make his own way carefully down the hill, under the shadows of trees again, the reins loose on his neck.

We came to a village at the foot of the hill. A pretty little place with a stream running alongside a bigger broader lane, and several of the cottages had little bridges over the water so that the householders could walk dry-shod to the road even when the stream was in flood. There were candles set at some of the windows to light the way home for weary men who had been out working late in the fields. I wondered idly what farm workers found to do at this time of year, perhaps ploughing? or planting? I did not know, I had never needed to know. I thought then, as Sea stepped like a ghost of a horse through the evening village, that there was precious little I did know about ordinary life; about life for people who did not dress up and dance on horseback. I thought then that I would have served Dandy a good deal better if I had worked on my skill at training horses for farmers and gentry rather than letting us be bound on the wheel of the show season. And now broken by that wheel, too.

The road went uphill out of the village and Sea brightened his pace and I let him trot uphill. If it had been light I guessed there would have been a great sweep of country on our left. I could smell the fresh greenness of it, and the hint of meadow flowers closing their little faces for the night. On our right was the high shoulder of the hill. The hill of the South Downs, I thought. I considered for a moment where I was.

I could see a map in my mind’s eye now. I was heading north from Selsey, I had skirted the town of Chichester, and this road must surely be the London road. That accounted for the firmness of the going, and the wideness of the track which was broad enough for two passing carriages for much of the way. That reminded me to keep a careful look-out ahead of me for toll cottages. I did not want to waste my money paying for use of the road when a little ride cross-country would save me a penny. I watched out too for coaches before or behind me. I did not want to speak to anyone, I did not even want them to look on my face. I had a silly belief that my face was so set and so stony that anyone looking into my eyes would cry for me. That they would see at once that I was a dead person looking out of a live face. That there was no one behind my eyes and my mouth and my face at all. I practised a smile into the darkness and found that my lips could curve and my face rise with no difficulty and with no difference to the weight of ice inside me. I even tried a little laugh, alone into the darkness of the fields on the far side of the village. It sounded eerie, and Sea’s ears went back flat and he increased his pace.

I checked him. I was so tired I did not think I could bear the jolting of his trot, and I felt as if I would never canter again. I could hardly remember the girl who used to vault on to the back of a cantering horse and dance with a hoop and a skipping rope. She seemed like a hopeful little child to me now, and I wondered idly why they had worked her so hard. Her and her poor little sister…I broke off my thoughts. It was odd. I was speaking and feeling as if I were an old woman. An old woman tired and ready for death.

The girl who had played in the sea this morning was a lifetime away from me now. I thought that I was more like the woman who had seen the wagon go away from her in that awful dream of the storm, and known that she would never see her baby again. The woman who had called after the wagon, ‘Her name is Sarah…’ I felt like that woman now. I felt like any woman feels when she has lost the love and the saviour of her life. Old. Sick at heart. Ready for her own death.

I sighed and Sea took it as a signal and broke once more into a trot which brought us over the top of the hill and down to the village which lay at its foot on the spring line.

It was getting later and the lights were doused in this hamlet. Sea went by in silence, not one man saw us pass. Only a little child looking from an upstairs window at the moon saw me go by. He raised his hand like a salute and his eyes sought mine, and he smiled a friendly, open little smile. I neither smiled nor waved. I hardly saw him, and I felt nothing when I saw his mouth turn down in disappointment that the stranger on the horse had not acknowledged him. I did not care. He would be worse disappointed than that before tomorrow was out. And I did not wish to be kindly to little children. No one had ever had a kind word for me when I was his age. No one had a kind word thereafter. Except she was kind to me. In her own light way, she had loved me. But that was little comfort now.

Quite the contrary.

It was a scattered little village this one. A public house with a lantern in the window the last building along the road, a little fir tree nailed above the door. I thought idly that perhaps I should stop and go in and eat and take a drink. I thought wearily of a bed and a warm fire. But Sea kept on walking and I did not care very much that I was cold and tired and hungry. Indeed I did not care at all. Sea’s head pointed due north and he scanned the road ahead of us with his shifting ears. I wondered idly what he heard.

What I could hear, what sung in my ears so that I shook my head irritably, was a high singing noise. Too high for human voices, too sweet for a squeaking hinge. It had started as soon as I had got into the saddle this afternoon, at Selsey. And it was calling me louder and clearer all along the road. I stuck my finger in one ear and then the other. I could not block it out and I could not clear it. I shrugged. It was all one with the clamminess of my skin and the cold inside my belly. The way my hands trembled when I did not remember to watch them and keep them steady. A singing in the air made little difference either way.

Sea broke into a trot again and I sat down in the saddle and let him go what speed he wished. I was far away in my thoughts. I was thinking of a summer years and years ago when she and I had been little grimy urchins and we had gone scrumping for apples in a high-walled orchard. I had been quite unable to face the thought of climbing up the wall or jumping down the other side and in the end had squeezed through a fence which had ripped half of my ragged dress off me. She had laughed at my scratched face. ‘I don’t mind being high,’ she had said.

I wished now that I had made her fear heights as I do, that I had somehow insisted that she always stay on ground level. That I had turned Robert against the idea of the trapeze as soon as he mentioned it. That I been warned by the barn owl. That I had remembered in time that the one unlucky colour in shows is always green.

Sea suddenly wheeled sharply to the right and nearly threw me off sideways. I clutched at his neck and stared around me. For some reason, clear only to his horse’s brain, he had turned off the main track and was heading down a little lane scarcely wider than a hay wagon. I stopped and thought to turn his head back towards the main road. But he was stubborn and I was too weary to be able to bend him to my will. Besides, it mattered so little.

I listened. I could hear the ripple of a river ahead of us in the darkness and I thought that perhaps he was thirsty and it was the noise of the clear water which was drawing him away from the road and down this little cart track. I let him go where he would, obeying my training which said that the horses must be fed and the horses must be watered. Whether you are hungry or thirsty or no. Whether you have forgotten what it feels like to want water or food. Still the horses have to be fed and watered.

He went easily down the dark slope towards the ford where I could hear the river rippling. The singing in my head was louder, clearer. It was almost as if it were coming from the river. The night-time air blew gently down the valley and set the trees sighing with the smell of new grass. There were tall pale flowers at the riverside and they glowed in the moonlight. Sea went out into mid-river and bent his proud head and drank. The endearing sound of the sweet water sucked in by his soft lips echoed loud around the little valley. I sat still on his back and felt the cool night air caress my cheeks, as soft a touch as a lover’s hand. An owl called softly to its mate one side of the river then the other, and as I sat there in silence, in the silvery moonlight, a nightingale began to sing a few clear notes which rippled like the river and were as clear as the singing in my head.

The trees stood back a little from the river and the banks were grassy with great clumps of primroses and sweet-scented violets. There were silver birches in a clump near a boggy patch of ground and their stiff catkins pointed spiky at the silvery sky. Sea blew out softly and when he raised his head from drinking it was so quiet that I could hear the water drip from his chin. Down river, the banks overhung the deep curves of water and there were dark standing pools where I thought one would find trout and maybe even salmon. Sea raised his head again, then lumbered awkwardly on the sandy river bed to the far side of the bank. I thought we should really turn back to the main road, but I was too desolate to think clearly about inns and stabling and a bed for the night. I let him have his head and he went smoothly and steadily on down the little track as confident as if he were going home, home to a warm stable for the night.

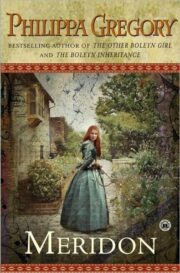

"Meridon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Meridon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Meridon" друзьям в соцсетях.