I had heard enough for one night. James Fortescue might be an astute man of business in Bristol and London – though I frankly doubted that – but in the country here he could have been cheated every day for sixteen years. He trusted entirely in one man who acted as clerk, manager and foreman. Will Tyacke decided what was to be spent and what was to be declared as profit. Will Tyacke decided what share individuals in the village could claim from the common fund. Will Tyacke decided on my share of the profits. And Will Tyacke was Acre born and bred and had no wish to see the Laceys taking a fortune from the village, or even claiming their own again.

My fingers touched the carved newel-post at the foot of the stairs and I heard a cool voice in my head which said, ‘This is mine.’

It was mine. The newel-post, the shadowy sweet-smelling hall, the land outside stretching up to the slopes of the Downs and the Downs themselves stretching up to the horizon. It was mine and I had not come all this way home to learn to be a pretty parlour Miss in that sickly pink room. I had come here to claim my rights and to keep my land, and to carve out an inheritance of my own whatever it cost me, whatever it cost others.

I was not the milk-and-water pauper they thought me. I was a rogue’s stepdaughter and a gypsy’s foster child. We had been thieves and vagrants all our lives, for every day of our lives. My own horse I had won in a bet, the only money I had ever earned had been for trick riding and card sharping. I was not one of these soft Sussex people. I was not even like their paupers. I was no grateful village maid, I was a baby abandoned by its mother, raised by a gypsy, sold by a stepfather and wise in every gull and cheat that can be learned on the road. I would learn to read the estate books so that I would know how much this fancy profit-sharing scheme had cost, and who were the rogues who were cheating me. I would take my place in the Hall as a working squire, not as the idle milksop they hoped I would be. I had not come home to sit on a sofa and take tea. I had come through heartbreak and loneliness and despair for something more than that.

I walked lightly up the stairs and sat for a while on the window-seat in my bedroom looking out over the sunlit garden, watching the pale clouds gather away to my right and turn palest pink as the sun sank towards them. ‘This is mine,’ I said to myself, as cold as if it were mid-winter. ‘This is mine.’

21

I woke at dawn, circus-hours, gypsy-hours: and I said into the grey pale light of the room, ‘Dandy? are you awake?’ and then I heard my voice groan as if I were mortally injured as I remembered that she would not answer me, that I would never hear her voice again.

The pain in my heart was so intense that I doubled up, lying in bed as if I had the hunger-cramps. ‘Oh Dandy,’ I said.

Saying her name made it worse, infinitely worse. I threw back the covers and got out of bed as if I were fleeing from my love for her, and from my loss. I had sworn I would not cry again as long as I lived, and the ache in my belly was too great for tears. My grief was like a sickly growth inside me. I believed that I could die of it.

I went to the window; it would be a fine day today. Before me was the prospect of another day of gentle lessons from Mr Fortescue, and a sedate ride with Will. Both of them watching me, both of them seeking to control me so that I would not threaten this cosy little life they had made here in this warm green hollow of the hills. Both of them wanting me to be the squire my mama had promised I should be – the one to hand back the land to the people. I grimaced like the ugly little vagrant I was. They would be lucky, they would be damnably lucky if I did not turn this place upside down in a year. You do not send a baby out into the world with a dying foster mother and a drunken stepfather and expect her to come home a benefactoress to the poor. I had seen greedy rich people and wondered at them. But I never questioned hunger.

Robert Gower was hungry for land and for wealth because he had felt the coldness of poverty. I was a friendless orphan with nothing left to me but my land. It was hardly likely I would give it away because the mother I had never known had once thought it a good idea.

It was early, perhaps about five of the clock. They kept Quality hours in this household, not even the servants rose till six. I went to the chest for my clothes and put on my old breeches and my shirt and swept my tangled red hair under Robert’s dirty old cap. I took my boots in my hand, and in my stockinged feet I crept out of my room and down the stairs and across the floor to the front door. I had expected there to be a heavy bolt and chains but as on the day I arrived, the door handle yielded to my touch. They did not lock their doors on Wideacre. I shrugged; that was their business, not mine. But I thought of the rugs and the paintings on the walls and the silver on the sideboard and thought they should be grateful that some friends of Da had never got to hear of it.

Out on the terrace I paused and pulled on my boots. The air was as sweet as white wine, clear and clean as water. The sky was brightening fast, the sun was coming up. It was going to be a hot day. If I had been travelling today we would have started now, or even earlier, and gone as far as we could before noon. Then we would have found a shady atchin-tan to camp and hobbled the horses and cooked some food. Then she and I would have idled off into the woods, looking for a river to swim or paddle, looking for game or for fruit or for a pond to fish. Always restless, always idle, we would not get home until the sun started to cool and then we would cook and eat again, and maybe – if we had a fair to go to, or a meeting ahead of us – we would travel on again in the long cooling afternoon and evening until the sun had quite gone and the darkness was getting thicker.

But there was no travelling for me today. I had found the place I had been seeking all my life. I was at my home. My travelling days, when the road had been a grey ribbon unfolding before me, and there was always another fair ahead, another new horse to train, were ended before my girlhood was over. I had arrived at a place I could call my own, a place which would be mine in a way those two raggle-headed little girls had never owned anything. Odd, that morning, that it should have given me so little joy.

I went around the house towards the stables. The tack room was unlocked too and Sea’s saddle and bridle were cleaned and hung up. I reached up and pulled down the saddle and held it before me, over my arm, and slung the bridle over my shoulder. I put my hand down to keep the bit still so that it did not chink and wake anyone. I could not have borne to speak civilly to anyone that morning.

That was odd, too. I don’t think ever in my life before had I pined to be alone, and I had always slept four to a caravan, and sometimes five. But when you live close you learn to leave each other alone. In this great house with all these rooms we seemed to live in each other’s pockets. Dining together, talking and talking and talking, and everyone always wanting to know if there was anything I wanted. If there was anything I wanted to have, if there was anything I wanted to do.

I walked through the rose garden, the buds of roses splitting pink as the petals warmed in the early sunshine, and I opened the gate at the end of the garden. Sea’s head jerked up as he noticed me, and he trotted towards me, his ears forward. He dipped his proud lovely head for the reins as I passed them over his neck and stood rock-still as I adjusted his bridle and then put his saddle on. For old time’s sake I could have vaulted on him, but the heaviness in my heart seemed to have got down to my boots, and I took him to the mounting block near the steps of the terrace as if I were an old woman; tired, and longing for my death.

Sea was as bright as the morning sky, his ears swivelling in all directions, his nostrils flared, snuffing in the scents of the morning as the sun burned off the dew. He had forgotten how to walk, his slowest pace was a bouncy stride as near to a trot as he thought I would allow. I held him to it while we were on the noisy stones in front of the house, but once we were on the tamped-down mud of the drive itself I let him break into a trot, and then into a fast edgy canter.

At the end of the drive I checked him. I did not want to go into Acre. Working people rise early whatever their jobs, and I knew that farming people would wake with the light just as I did. I did not want them to see me, I was weary of being on show. And I was sick of being told things. Taught and cajoled and persuaded as if I were an infant in dame school. If one more person told me how well Wideacre was being run – as if I should be pleased that they were throwing my inheritance away every hour of the day – I should tell them what I truly thought of their sharing scheme nonsense. And I had pledged myself to hold my tongue until I really knew what this new world, this Quality world, was like.

I turned Sea instead towards the London road, the way we had come all those nights ago, fleeing from what now seemed like another world. The way we had come slowly, slowly, in the darkness up an unfamiliar road, drawn as if by a magnet to the only place in the world where we would be safe. Where they had prepared a homecoming for me – only by the time I got there, I was not the girl they had wanted. It struck me then, as Sea stepped lightly down the road, that I was as bitter a disappointment to them, too. They had been waiting all these years for a new squire set in the mould of my real mother: caring for the people, wanting to set them free from the burden of working all their lives for another man’s fields. Instead they had found on their doorstep a hard-faced boyish vagrant who could not even stand the touch of a hand on her arm, and who had been taught to care for no one but herself.

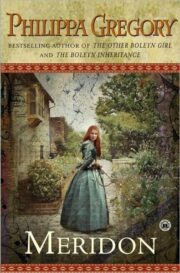

"Meridon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Meridon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Meridon" друзьям в соцсетях.