Bulgakov lived on the top floor in the corner apartment of a repurposed nineteenth century house that had once belonged to the paramour of the Dutch Vice-Consulate to Russia. His particular space, at one time the modest spare dressingroom of its former occupant, was oblong in shape though still had good light and was of sufficient size to fit the Moscow code for the standard housing allowance without requiring some crude refashioning of partitions or walls. The room formed itself into two spaces by a decorative archway that spanned the narrower of the two dimensions. The larger space was beyond this division; here Bulgakov’s bed fit into the far corner, next to it a small side table with a single drawer; its spindle legs were obscured by multiple stacks of books. On the wall a modern utilitarian sink had been added later and with remarkably poor workmanship. The newer plaster used to fill the oversized hole lacked the creamy texture of the original walls, and was perpetually collecting on the floor in irregular powdery piles. No effort had been made to repair the wall below it. Since Bulgakov had lived there, the spigots hadn’t produced a drop and he suspected the pipes were never connected. A table with chairs sufficient for two, or in a pinch, three, if the third was willing to sit on the bed, was pressed against the wall. On the other side of the arch, nearer the door, a short sofa with an armchair made up a small sitting area with a squat table between. Bookcases stood on both sides of the chair. These were filled and double-layered, with yet more books in varying stacks on the floor in front, as if waiting in queue. Squeezed between a bookcase and the archway, a narrow wardrobe fought for space.

Few remnants of the room’s previous Dutch life remained: the floorboards along its perimeter were finished with a row of Delft tile; each square was slightly larger than a woman’s hand, painted in shadowy blues and baked in the kilns of that famous factory town. Each was a quiet and singular scene of bucolic seventeenth century meditation without repeat. By some miracle of neglect or more likely ignorance, not a single tile was missing or damaged save one. As if with the thoughtlessness of a blind scalpel, the piece had been parted in two with a gentle curving swipe, leaving behind a young Dutch maiden, holding in her hands the strand of pearls she wore, extended upward, to show to her vanished partner. Another maiden? Her mother? Some young man who’d come to woo her? She was forever alone, her gaze held captive by those opalescent whorls now long divorced from their meaning.

When the agent had finished reading, he leaned forward in the chair; the collection of papers in his hand he’d rolled into a baton. The rest of the apartment was unrecognizable. His gaze came to light on the fragment of tile along the baseboards. A remnant of another time; so many clung to these kinds of things. He rubbed his eyes. What was the take, he asked of the others, as if tired of it all.

Numerous manuscripts. Poems from the poet Mandelstam. A few letters. In truth, little of interest.

“Good,” he said. He stood and slipped the roll of pages into the side pocket of his raincoat. One of the agents asked if he’d like to keep the poems. “No thank you,” he said, his hand loosely touching his coat pocket.

He told them to wait for the writer’s return.

Bulgakov’s first impression when he entered was that his apartment had been quite suddenly enlarged. The walls were bare and open and very white. Then he saw the books were gone from their shelves, the prints from the walls. They lay thick on the floor, like ancient tiles pushing up and sliding over a shifted landscape. Two agents waited, dressed in dark suits, one sitting in his armchair, another on the sofa. It was impossible to tell for how long. First one stood, then the other.

Bulgakov asked if he might leave behind a note, a possible explanation. But he stopped there; he didn’t want to suggest that someone in particular might be looking for him.

The agents told him no and for a moment he was relieved by their answer.

They nodded toward the door and his relief disappeared.

CHAPTER 7

In the fall of 1917 Nadezhda was pretty and slender, with large dark eyes and good skin on which she prided herself. She worked as one of the typists on Stalin’s armored train. She’d bully him when he came back to their car with his revisions and corrections. She called him the Great Man; she’d complain of his handwriting, his atrocious grammar, the things she had to put up with. The other girls would giggle and watch them together. She’d smile and lean toward him. They were old family friends; she’d known him since childhood when her parents had sheltered him during one of his escapes from Siberian exile. He gave his work only to her. “Perhaps you can teach me,” he’d say, and wag her chin between his fingers. She was sixteen and living away from her mother, filled with purpose and unafraid. She saw how the men feared him; her fearlessness placed her above them.

At night, however, when they worked alone on his speeches or his party communications, she was all business. “You alone I trust,” he told her. One night he tried to kiss her. He’d come for the latest revision of a memorandum; she rose from her chair and handed it to him. The last several changes had simply been the rephrasing of a single sentence; he’d gone back and forth with it. She’d made the changes without complaint; the preponderance of evidence of their crimes against the people calls for the execution of these four men. In the alternative version, there were four men and a woman. The tapping of her keys took a life then gave it back. She watched him read over the words. The car was dark except for her desk light; he held the page under it. The train lurched and she swayed. He commented on the hour, how she must be so terribly tired. He brushed his hand over her head, her hair, seemingly with absentminded affection. She told him she was fine. It pleased her to be a help. To him with his important work. With her words, he turned to her, lifted her face, searching for her lips with his. She stepped back with surprise and his groping became awkward. He stepped toward her. Her legs pressed against the desk behind her. The lamp clattered against the typewriter, shining light across the room. She panicked and turned her face away and he kissed her cheek. He stepped back and wagged his finger at her.

“I’ll tell your mother on you,” he said, smiling.

“I’ll tell my mother on you,” she said. Her words carried a breathy seriousness and with them he changed; his face stilled and she was sorry for having said them. He stepped back further and thanked her for her efforts. She didn’t want his thanks. He told her to get some sleep now. She didn’t want sleep. He took the page with him. The woman would die.

In the weeks that followed, she sensed his affection for her had cooled. She no longer teased him as she had before. He gave his work to other girls of the typing cadre. They did not complain as she once had. She felt herself sinking into a pool filled with the others.

One night, weeks later, they were celebrating the Red Army’s victory over Kiev. In the dining car of their train there was liquor and dancing. Stalin sang a Georgian lament. Nadezhda watched from across the car, unable to catch his eye. Later that evening, he flirted with a communications officer, a tall Tatar girl. The girl sat somewhat rigidly on the edge of one of the booth seats; he leaned over her, one hand against the top of her seat, the other on his thigh, as though waiting for its occasion. Nadezhda put off the advances of a young lieutenant. She waited until Stalin had retreated to the back of the car to replenish his drink and she followed him there.

In the near darkness of the corridor, she plucked his sleeve. He smiled at her easily, she thought, as if she’d slipped his mind and now that he remembered it was the same as before. His eyes were glassy with liquor. She took his hand and led him into the lavatory. She locked the door, undid his belt and lifted her skirt for him. She wasn’t wearing her undergarments. The cool of the air against her skin was surprising. She was a virgin. She watched somewhat distantly as his square hands reached for her bare hips. This was what she’d wanted.

Later, shortly before they married and after one of the rows for which they would become famous, she sat on his lap and touched his face, smoothed his hair back from his forehead, and kissed him on the cheek where the redness from one of her earlier slaps still remained. She laughed lightly. “I told Pavel, if anything happens to me, anything, you know. It would be you.”

His waxen face never moved with her words. The moustache lifted slightly; it was almost imperceptible.

She knew in that moment she’d condemned her brother and his family as well as herself.

One agent drove. The other sat in the back beside Bulgakov; this one stared out the side window as if bored. Flattened cigarette butts littered the floor around his feet; the agent shifted occasionally in the cramped space. The air had a dusty odor. Neither gave any indication of their destination. The car seemed to be of its own mind as they negotiated the grid of streets. With each turn Bulgakov hoped to detect some reaction from the agents. By all appearances, for all their concern, they could have been transporting livestock or corn.

A horizontal crack extended through the side window, transecting trees and buildings and pedestrians. They passed a woman with a perambulator; a lone man in a suit sitting on a bench, his arms crossed over his chest. A breeze lifted and threatened to dislodge the man’s hat. They disappeared beyond the edge of his window with their smallish worries. He did not figure among them. On the seat in front of him there was a smear of something—possibly blood. They did not care.

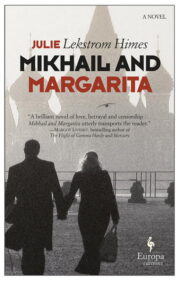

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.