‘I wouldn’t leave you in distress,’ John said, preening himself, apparently oblivious to Cat’s incredulity. ‘That’s what friends are for. And brothers, obviously.’

‘You’re a mate,’ James said. ‘I don’t know what I’d have done otherwise. I don’t have roadside assistance.’

Neither, it transpired, did John. They might have been expensively stranded for hours had it not been for Cat. On their earlier trip to North Berwick, she had been so determined not to pay attention to the journey itself that she had memorised every detail of the car’s interior, including the sticker with the emergency number for the car’s dedicated rescue service. When John called them and explained the situation, they reluctantly agreed to help. Cat suspected it was easier to give in than to have John Thorpe hector everyone in the company hierarchy until he finally got the answer he required.

Nevertheless, it was late afternoon by the time their small convoy was mobile again. ‘It’s too bloody late for Linlithgow now,’ John whined.

‘And for Glasgow,’ Bella said. ‘We’re supposed to be at Ma’s charity poker evening tonight, don’t forget.’

And so they set off to return to Edinburgh. ‘If your brother had a decent set of wheels, we’d have had a great day out,’ John complained bitterly. ‘It’s a false economy not to have a good motor.’

‘It’s not if you can’t afford it.’

‘And why can’t he afford it?’

‘Because he’s not got enough money?’ Cat knew she was being snippy and she didn’t care. Besides, she’d come to realise that John Thorpe was so thick-skinned he didn’t notice.

‘And whose fault is that? If there’s one fault I can’t abide, it’s being tight with money. It’s a man’s duty to spend his money and keep the economy turning, not hoard it like a miser. And money’s never been cheaper.’ He fulminated in this vein for a while, but Cat tuned him out. She was long past the point of being polite.

Back at Queen Street, the Thorpes and James invited themselves up for a drink. Before Cat could even put the kettle on, Susie emerged from her bedroom wrapped in a silk kimono. ‘You’re back,’ she said, ready to state the irrefutable as ever.

‘Things didn’t quite work out as planned,’ James said, abashed. ‘My fault, Susie.’

‘That’s a shame. You would have done better to stay here after all, Cat. Because you just missed Ellie and Henry. Not more than ten minutes after you’d left. They were terribly apologetic about being so late, but apparently the General had invited some people around for morning coffee and they had to hang around and make small talk. Too boring, Ellie said. But apparently when the General says jump, they all jump.’

‘Couldn’t she have texted me?’ Cat said.

‘She tried to, but when you swapped numbers last night, she got one digit wrong on your number. So she’s been texting some complete stranger who finally lost her temper and sent back a really rude message. Poor Ellie. The girl was mortified.’

Bella made a sound that somehow conveyed both disbelief and contempt. ‘So you see, Cat, you’ve got nothing to reproach yourself with. It was totally Ellie’s fault after all. She’s the one who cocked everything up. Me, I’d never put a friend through that, even if it meant falling out with my mother. John’s the same, aren’t you, sweetie? You can never bear to let a friend down.’

It was the final irony. And although Bella pressed hard for her to join them, Cat was not sorry to see the other three leave for their poker evening. She supposed she must have had a more disappointing day in her short life, but she was damned if she could bring it to mind.

12

Cat hated people to think badly of her; she was so distressed at the possibility of having unwittingly upset the Tilneys that she spent much of the night in restless wakefulness, rehearsing how she might explain the events that had overtaken her. At breakfast, she could barely eat, satisfying herself with nibbling toast and sipping tea. ‘Is it too early to go round to the Tilneys?’ she asked as the clock hands crept towards nine.

‘I wouldn’t thank you for turning up at this time,’ Mr Allen said from behind his paper and his coffee.

‘That’s all very well, Andrew, but people have tickets for festival events from quite early in the day. There are Book Festival events that start well before ten, if you can believe it,’ Susie said. ‘Of course, if they’re not early risers, they won’t welcome an early visit.’

It was all very well lecturing young people about the value of listening to their elders, Cat thought mutinously. But what was she supposed to think when they gave completely opposing pieces of advice? She finished her tea and stood up. ‘I’m going round to Ainslie Place right now,’ she said. ‘I’ll walk past the house and see if there’s any sign of life. And then I’ll decide whether to knock or wait.’

Mr Allen grunted. ‘Sensible girl.’

Although the sky was overcast with high thin cloud, Cat didn’t think it looked like rain, so there was little risk in walking the short distance to the Tilneys’ rented house without a coat. She set off briskly, but slowed as she turned into Ainslie Place, an oval of elegant Georgian buildings with private gardens in the middle. On one side, there were tall five-storey tenements, divided into flats. But the Tilneys had rented on the smarter side of the gardens. No mere flat for them; they had taken an entire house for the month of August. Cat had learned enough from the conversation in Edinburgh to understand that represented an eye-watering outlay of cash. The knowledge did not make her envious however; she was more than happy with her lodgings, more than delighted to be in Edinburgh at all.

Cat made her first pass of the Tilneys’ house, surreptitiously eyeing the windows. All the curtains seemed to be open, and she could see dim electric light through the muslins that draped the ground-floor windows. There was definitely life inside the house. She walked to the corner and turned into the side street. She stopped, breathed deeply until her fluttering stomach had calmed itself, then walked back to the Tilneys’ front door. She puzzled briefly then pulled a gleaming brass knob and heard the distant pealing of a bell.

A long moment passed then the door swung open soundlessly to reveal a gaunt, pale figure with perfectly barbered grey hair. His clothes were almost – but not quite – a military uniform. ‘May I help you?’ he said, his voice brusque, his brogue unmistakably Scottish.

Cat managed a faint smile. ‘I’m looking for Ellie Tilney,’ she said.

He looked her up and down. ‘And who shall I say is calling?’

‘Cat Morland. Her friend Cat. Catherine. Is she in?’

‘I believe so. I’ll go and see.’ And the door was firmly shut in her face. Cat knew she was unaccustomed to the habits of the rich and powerful, but she couldn’t help feeling there were better manners to be found in the villages of Dorset. She hung around on the doorstep, trying not to look like someone who might be intent on persuading the inhabitants to change their electricity provider. After what seemed like a very long time, the door opened again. ‘I’m sorry,’ the man said. ‘I was mistaken. Miss Eleanor is not at home. I’ll tell her you called.’

Before Cat could respond, the door was closed again. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d felt so mortified. He’d treated her like she was completely insignificant. And as if that wasn’t bad enough, she wasn’t at all sure she believed what he’d told her. She climbed down the steps slowly, casting a sideways glance at the drawing-room curtains, as if she half-expected Ellie to appear at the window, making certain she’d really left.

Cat trudged down the street, head lowered and spirits lower still. When she turned the corner leading her towards Queen Street, she leaned on the railings and stared back down the curve of the street as if that would summon the Tilneys to her. In apparent answer to her yearning, the door swung open and General Tilney marched down the steps to the street. He looked back at the house and spoke sharply. To Cat’s dismay, Ellie ran out of the house and caught up with her father as he walked on round the crescent away from Cat.

Disconsolate and dejected, Cat had no choice but to head back to the Allens’ flat. She had been thoroughly humbled – no, humiliated – and she had completely lost her appetite for culture. In spite of Susie’s attempts to get her to the Book Festival, Cat insisted on remaining at home, furious with herself but even more furious with John Thorpe and his forcefulness. She couldn’t even bear to go on Facebook or Twitter because she didn’t have the energy to lie or the chutzpah to tell the truth. It occurred to her that although she had initially seen Ellie Tilney purely as a conduit to her brother, she had quickly grown to like the young woman for herself. Losing the prospect of her friendship was almost as cruel a blow as losing the chance of becoming Henry’s – dare she think it? – girlfriend.

When Susie returned late in the afternoon, laden with shopping and full of gossip that meant nothing to Cat in her mournful state, she was insistent that her young charge should get in the shower and prepare for that evening’s excursion to the ballet. Cat was resistant at first, but it gradually dawned on her that she’d spent long enough being miserable without distraction, not to mention that she’d never seen a proper ballet even though she was quite certain dance was an art form whose language she understood. ‘Besides,’ Susie said, clinching it, ‘you never know who you might see.’

Mr Allen’s connections had provided them with a box, which Cat was excited about until she discovered Susie had invited Martha Thorpe along. Fortunately, only Jess and Claire had chosen to come; James and Bella had apparently managed to get tickets for the recording of a BBC radio comedy show, which they thought would be more to their taste than modern dance. ‘Johnny’s somewhere around,’ Martha said vaguely. ‘He doesn’t like the ballet, but he enjoys socialising.’

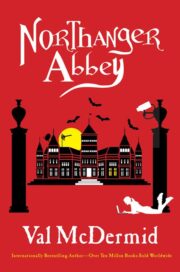

"Northanger Abbey" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Northanger Abbey". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Northanger Abbey" друзьям в соцсетях.