‘Thank you.’ Cat gave an uncertain smile. ‘This is an amazing house.’

‘Aye,’ Mrs Calman said. ‘If these walls could talk ...’ She turned to Ellie. ‘Don’t forget now, Eleanor. I’ll be putting the soup on the table in half an hour. Whether you’re there or not.’ She nodded at them both and left, closing the door firmly behind her.

‘Wow. She’s a bit of a dragon,’ Cat said.

‘She used to be in the army. That’s how she met Calman. I think they both think that working for Father is as close as it gets to still being in uniform.’

‘If it was a novel, she’d have been the one who clasped you to her bosom after your mother died and revealed her previously unsuspected heart of gold.’

Ellie snorted. ‘Trust me, my life is definitely not a novel. We’d better get ready for dinner. I’ll meet you at the top of the stairs in twenty minutes.’

Cat looked at her jeans and T-shirt. ‘Should I get changed?’

Ellie gave her a critical once-over. ‘Jeans are OK, but I’d lose the T-shirt. Father likes to pretend the last hundred years never happened.’

They parted in the hallway and Cat hurried back to her room. She decided to ditch both the jeans and the T-shirt in favour of a long floaty skirt layered in different shades of green and blue, topped with a plain white cambric blouse. If the General wanted to live in the past, she’d do her best to be a demure young woman. She looked longingly at the japanned chest, but told herself to be patient, to wait till the house had settled down for the night. Just as well she had, for only moments later, Ellie knocked on her door, impatient for her company.

Although Cat and Ellie arrived in the drawing room a full five minutes ahead of the deadline, pink and panting from running down the corridor and stairs, the General was staring ostentatiously at the elegant grandmother clock in the corner. Henry was already there, done with devilling, sipping at what Cat fervently hoped was a Bloody Mary. ‘Just in time,’ the General said. Cat thought she heard a tinge of disappointment in his voice and scolded herself for the unworthy thought.

As Mrs Calman served the soup, Cat drank in the details of the grand room. Everything gleamed and glittered with polished wood, silver and crystal. The table was easily big enough to seat a dozen or more, but it came nowhere near filling the space. Seeing her scrutiny, the General said, ‘You must be used to far grander dinners than this with your benefactors, the Allens?’

Surprised, Cat shook her head. ‘No, not at all. The Allens don’t do much formal entertaining down in Dorset. We generally go round for kitchen suppers.’

He nodded sagely. ‘I suppose there’s not much of a choice of guests down in that part of the country. Not like here in the Borders. It will be different with the Allens in London, I’d lay money on that. I’m sure that Mr Allen knows exactly what he’s doing when it comes to impressing people with his success.’

Perplexed, Cat wasn’t entirely sure how to respond to that. She knew Mr Allen had to impress people with his instinct for theatrical successes, but she didn’t think he did it with ostentatious displays of wealth.

‘He’s certainly very successful,’ Henry said, seeing her uncertainty. ‘But not everyone feels the need to display their achievements materially.’

The General raised his eyebrows in disbelief, his face growing pale with annoyance. ‘Then how are people to know where you have reached in the hierarchy of things? Sometimes, Henry, you sound almost like a socialist.’ He said the word as if it were the worst insult he could hurl across a dining table with ladies present.

‘I think people should live in the style that suits them best, so long as they can afford it,’ Cat said. ‘Not everyone has the good fortune to be able to live somewhere as wonderful as Northanger Abbey.’

Mollified, the General grunted and finished his soup. When he was so brusque, Cat couldn’t help but think wistfully of the kindness and conviviality of the Allens. But when he left the young people to their own devices, Cat was as happy as she’d ever been. Thinking of the Allens reminded her that she had been unable to communicate with any of her nearest and dearest for almost a whole day.

‘General Tilney?’ She spoke with some diffidence as Mrs Calman cleared away the soup dishes and placed a selection of curries and side dishes in the middle of the table. ‘I wonder whether it might be possible for me to use your wifi?’ She caught the look of alarm shared by Henry and Ellie.

‘The wifi?’ The General frowned. ‘Is that entirely necessary?’

‘I wanted to check my email.’

‘My dear girl, why? Your parents and the Allens know precisely where you are and have the telephone number, so if there were any urgent need to contact you, there would be no difficulty.’ He spooned rice on to his plate and added some lamb methi. ‘You don’t have any kind of job yet, so there can be no urgent business communication awaiting you. In short, Catherine, there’s no conceivable reason other than the purely frivolous for you to “check your email”. Isn’t that so?’

Cat was taken aback. Never before had an adult lectured her thus nor attempted to keep her from the constant to and fro of social media. ‘I suppose,’ she said.

‘So there is no need for me to make myself vulnerable to the phreaks and hackers out there who are just waiting for the chance to read my secure emails and plunder our bank accounts. There is no reason why you should be aware of this, but I receive communications that could conceivably be useful to the enemies of our country. We use the wifi sparingly here. I choose not to take risks with my security or the security of the nation.’ It was a virtuoso display of pomposity and self-importance thinly disguised by the General’s tone of regret.

Chastened, Cat devoted herself to Mrs Calman’s curries, which were spicy enough to take her mind off any grievance against the General. Before dessert was served, he left the table, saying, ‘I have an MOD briefing to take a look at. Enjoy the rest of your meal. I’ll see you in the morning.’

When he left the room, Henry said, ‘He still does consultancy work for the army. He’s very cautious about security.’

‘Paranoid, more like,’ Ellie muttered.

After dinner, the trio retired upstairs to their sitting room and played a supremely silly game on one of the consoles, laughing and mocking each other’s efforts. The evening slipped by in an entertaining blur, and Cat couldn’t help thinking how well Henry and Ellie would fit in with the Morlands. Provided, of course, that she was mistaken about the whole vampire thing. Perhaps she’d discover more clues to help her make her mind up when she explored the mysterious japanned chest in her room.

By the time they separated and went to bed, the night was stormy. The wind had been rising at intervals the entire afternoon, though Cat had failed to notice it. Now it howled in dramatic gusts, bringing noisy scatters of rain with it. It was awesome, Cat thought as she made her way down the long corridor to her room. She nearly jumped out of her skin when a particularly loud gust was followed by the distant slam of a door. It was impossible to escape the sensation of having been dropped into an episode of the Hebridean Harpies’ adventures. Northanger Nixies, perhaps, given how much water was pouring down her windows when she finally reached her room.

Cat pulled the curtains closed but they didn’t stop moving when she stepped away from them. ‘It’s the wind,’ she said firmly. ‘Just the wind.’ To make doubly sure, she pulled each curtain swiftly back and checked the window seat. Then she put her hand up to the window and felt the damp draught where the ancient frames had warped enough to let the night in. ‘It’s the wind, you moron,’ she said to herself, letting the curtains fall.

She eyed the chest, but, recognising the deliciousness of deferred pleasure, she decided to get ready for bed first. Then, with clean teeth and freshly laundered pyjamas, she approached the lustrous black chest. Cat gripped the edge of the lid and attempted to lift it. She was surprised by how cold and heavy it was until she realised it was made not from wood but from metal. She changed her grip and put more effort into it and this time she was rewarded with success. The lid rose and she rested it against the wall, careful not to make a sound. Not that it would have made any difference if she had, for by now the night’s peace was regularly broken by rumbles and claps of thunder as the storm took hold.

To Cat’s disappointment, what was revealed was nothing more exotic than a hand-pieced quilt. It was true that the fabrics were of rich, jewelled colours, the pattern mathematically precise and intriguing and the stitches tiny and neat. But still, it was only a quilt. Cat drew it out of the chest and shook it out. It was big enough to act as a spread for a single bed. A hand-written label in one corner caught her eye and she pulled it close. ‘Margaret Tilney fecit 2001,’ she read. Cat, who had learned a little Latin from the memorial tablets in her father’s churches, thought ‘fecit’ meant ‘did’, which made a sort of sense. Margaret Tilney did it in 2001. She remembered Ellie that afternoon referring to her mother’s quilting. This must be one of her quilts. She was holding in her hands the very fabrics that the General’s dead wife had held. Her DNA was mingling with Henry’s mother’s even as she had the thought. Cat didn’t know whether to be spooked or gratified.

She spread the quilt out on her bed then returned to her chest. She was surprised to see that the quilt was not the top item in a pile of bedding. Instead, it had sat in its own shallow drawer. She studied the chest again and realised it should now be possible to open the double doors at the front. She tugged at them, but they remained puzzlingly closed. She ran her hand along the inside of the drawer and her finger snagged on a metal hook almost flush with the wood.

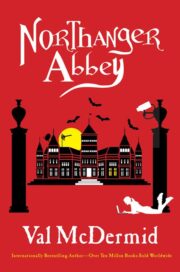

"Northanger Abbey" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Northanger Abbey". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Northanger Abbey" друзьям в соцсетях.