There was a big pause.

“Her father's a wonderfully gentle man. And so is she.”

Jazz thought she was going to start weeping.

“And how is she different from all your boys?”

“Well,” said the woman, “she goes through clothes like they're going out of fashion.”

Sheer fatigue made Jazz start giggling.

“I'll have to go now,” said the woman. “She'll be wanting another feed. Can you phone me back the same time tomorrow?”

If my brain hasn't melted by then, thought Jazz. She put the phone down and let out a heartfelt scream and dropped her head onto her desk.

Mark looked up. “What do you get if you cross a woman's magazine and a cat's arse?” he asked through his bacon buttie.

Jazz shrugged without moving her head. She was utterly exhausted.

“Fucking expensive cat litter,” he grinned.

Jazz looked up and frowned at him. “Mark,” she managed, “have you ever thought of becoming an after-dinner speaker?”

He beamed.

The phone went. Jazz hated answering the phone at work.

“Hello, Hoorah!” she said as gravely as she possibly could.

“Jasmin Field please,” said a highly efficient voice.

“Speaking.”

“Oh hello, this is Sharon Westfield at the Daily Echo,” said a person for whom this information was most impressive. “We're looking for a new columnist for our woman's page and read the piece about you in the Evening Herald. I'll be completely honest with you — always am. Loved your attitude. Loved your sister Josie. How different she is from you — married, a young mum with a good sex-life, happy family.”

Jazz mumbled a sort of yes sound. She'd always detested the Daily Echo; it was a shabby tabloid full of horror stories and scantily clad "girls" who wore "panties". But there was no denying that it had the second largest circulation of all the daily papers, and once you've written for the Daily Echo, all sorts of doors start opening for you. Weirdly though, Jazz didn't feel as impressed today as she might have done a week earlier.

“You see,” Sharon Westfield continued, “that's just the sort of new angle we're looking for. Sort of post-Bridget Jones, post-ironic, post-modern, post-post-feminist sort of thing. D'you see? Women being content and capable. It's so new. Very exciting.”

“Ye-es,” said Jazz dubiously.

“We'd like you to write us three provisional columns of twelve hundred words each. And remember, our readers are right-wing bordering on fascist, chauvinistic bordering on misogynistic - especially the women - and, of course, thick as pigshit. These are people who record Jeremy Beadle. Try and remember all that while you write, it'll save you having to do a re-write. That will be, what? Five thousand pounds?”

Jazz couldn't speak.

“OK - call it seven and a half. Fax it to me by Monday. Triple four, double five, double three. For the attention of Sharon Westfield. Ciao.”

Jazz put the phone down, bubbling with anger and excitement in equal proportions — a reaction that was becoming strangely familiar.

“What was that?” asked Mark, intrigued. Jazz rarely remained monosyllabic on the phone.

Jazz told him.

“Jeez, some people have all the luck,” he said.

“You think I should go for it?”

“Are you stark-bollocking mad? Of course you should go for it! A column at the Daily Wacko? You'd be set up for life.”

“Even if it means selling out bigtime?”

Mark frowned. “What do you mean?”

“Never mind.”

Jazz had the rest of the week to consult George and Mo. And, of course Josie. But there were other things on her mind that she had to sort out first.

Jazz sat on the sofa in her room, the soft sound of monks chanting from her stereo speakers rocking her into a calm state. Now that she had sorted out in her mind why the e-mail had distressed her so much, she realised there was information in it that she should act on. Maybe. She decided she had to speak to George. She needed some advice from someone with strong moral fibre and a heart of gold. She stretched out to the phone behind her.

“Are you going to tell me you can't babysit for Josie tomorrow?” asked George.

In her bewildered state, Jazz had completely forgotten about that. George and she now took it in turns every Thursday night to babysit Ben while Josie and Michael went out together. Jazz was constantly impressed by their marriage. Josie deserved to win an award, whether or not it was under Jazz's name.

“No, that's fine, I can still do tomorrow,” she answered.

“Oh, OK,” said George disappointedly. Then: “Can I come too?”

Oh poor heart, thought Jazz. “Of course,” she said in a jolly voice. “It'll be much nicer with you there.”

“Do you still want to talk tonight?” asked George hopefully.

“Yes, come round,” said Jazz. “I'll make pasta.”

It was a date.

When George turned up, Jazz had to hide her shock at her sister's appearance. She looked almost emaciated, although she was smiling more than she had been for a while.

“I feel fine,” assured George. “I just don't seem to want any food.”

“Well, you'll eat everything I serve you tonight,” said Jazz firmly.

“Yes, Mum,” said George.

George picked at the pasta, but managed nearly all of her salad. Jazz watched her in near despair. She had always thought being single would be good for George but now she wasn't so sure. Her sister was practically wilting away before her eyes. Jazz waited until they were drinking coffee and George could concentrate on the matter in hand completely. Maybe it would do her good to think of something else; be made aware that her brain had to go on for others, if not for herself. Slowly and clearly Jazz told George about Harry's e-mail and, more relevantly, the true story about William Whitby. The shock registering on her sister's wan face made it look more animated than it had in days, but she said nothing.

“What should I do?” asked Jazz at last.

“What do you mean?” asked George back. “Do you want to apologise to Harry?”

“No,” said Jazz, pained. “I mean, what should I do as a journalist? Wills - William — is adored by the public because they think he's like the priest he plays. And I'm a journalist who knows the truth about him. George, he's an alcoholic woman-beater. What the hell should I do?”

George looked dumbfounded. “We-ell,” she started.

“I mean, there's legitimate public interest here,” rushed Jazz. “Should I shop him now and watch his career die — when he's never done anything to me except be positively charming -or do I wait silently, knowing that while the world thinks he's a really nice guy, he's probably beating up his make-up woman?

George frowned deeply. Jazz continued regardless.

“All I have to do is phone any features desk and William Whitby's career is over. And by sick coincidence, mine is made. What the hell do I do?” Jazz was pacing now.

George was beginning to look a little bit more certain. “You sit pretty,” she said fixedly.

“I let him go on beating other women?”

“No, I didn't say that. You don't know what went on behind closed doors between him and Carrie.”

“You mean she might have been asking for it?” asked Jazz crossly.

“No, I didn't say that,” repeated George calmly. “I mean he may never do it with anyone else. Or he may have stopped drinking.”

“But surely it's my duty as a journalist to inform—”

“No, it's not your duty,” George interrupted. “First of all, press coverage — even about something as sordid as this - “might give him more fame than he deserves. Secondly, Harry told you in confidence. And thirdly, it's not even Harry's secret to tell, it's his sister's. And it sounds as if she would hate to have her name brought into anything.”

Jazz was convinced.

“Of course,” she said finally. “You're right - it would kill her. Who am I to do that to her?” She plonked herself down at the table. “Thanks George,” she said wearily.

They sat in glum silence.

“Of course,” said George quietly, “you could always let William know that you know about him and Carrie. Keep him on his toes a bit.”

Jazz looked at her sister in a new light. “You clever, conniving thing. Of course! What's happened to you? Am I slowly having a wicked effect on you?”

George tutted loudly. “Just because I'm not a cynical hard bitch, there's no need to treat me like I'm Beth from Little Bloody Women!”

Jazz smiled thoughtfully and wondered if that's who she should try emulating from now on.

“I'm afraid there's something else I need your advice on,” she said softly.

George listened to her career dilemma. Should Jazz start writing for the Daily Echo? Could she do that and keep a part-time job at Hoorah! just in case the column wasn't successful? At the end, George asked one simple question: “How will you feel about yourself if you write for the Daily Echo?”

Jazz thought hard. “I suppose I'll feel wretched in one way, but then this is my career. This is everything I've worked for. This is my life, it's who I am. It's me.”

“Then do it.”

“But I hate everything this rag stands for.”

“Then don't do it.”

Jazz looked at George. Her eyes seemed dead.

By a fluke, Mo was in the flat the next night. And of course, Gilbert was there too. Although Jazz didn't want to talk in front of him, she knew she probably wouldn't get Mo alone for months - if ever again, she thought sourly. Gilbert lived on his own half an hour away and Mo had practically moved in with him. She hardly lived in her own flat any more. For weeks now, there had been none of her underwear airing in the bathroom, none of her mugs left unwashed on the sideboard and none of her shoes lying scattered in the hall. Jazz missed her terribly, especially during this period of monumental self-doubt and depression. Her father had been right. She was desperately jealous of Gilbert.

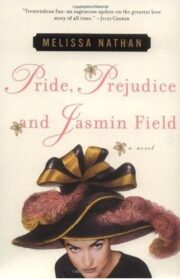

"Pride, Prejudice and Jasmine Field" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pride, Prejudice and Jasmine Field". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pride, Prejudice and Jasmine Field" друзьям в соцсетях.