At nine-thirty, just as it stopped raining, Freddie’s freshly cleaned red Jaguar roared up the drive.

‘Oh dear,’ said Freddie, leaning out of the window and roaring with laughter at the other guns’ filthy Landrovers, ‘I forgot to chuck a bucket of mud over my car before I came out. Amizing, those snowdrops,’ he said, clambering out. ‘Just like a big fall of snow.’

He was wearing a red jersey, a Barbour and no cap on his red-gold curls. Next minute Valerie emerged from her side in a ginger knickerbocker suit, with a matching ginger cloak flung round her shoulders, and a ginger deerstalker.

‘Christ,’ muttered Tony to Sarah Stratton.

‘It’s Sherlock Lovely Homes,’ said Sarah, making no attempt not to laugh. ‘All she needs is a curved pipe and a spy glass.’

‘What’s that?’ asked Valerie gaily.

‘We were admiring your — er — outfit,’ said Sarah quickly.

‘All from my Spring range,’ said Valerie, looking smug. ‘Better hurry, it’s selling like hot cakes.’

Tony oozed forward, exuding charm.

‘You both know Sarah and Paul Stratton of course, and my brother Bas,’ he said smoothly, and when he went on to introduce Valerie to the Lord-Lieutenant Henry Hampshire, two peers and a Duke from the next county, Valerie nearly had the orgasm Freddie had so longed to give her earlier. Fred-Fred must definitely join the Corinium Board, thought Valerie. It might be a Prince, or even a King, next time.

‘Hullo, Valerie,’ said Monica, who was wearing a green sou’wester over a headscarf. ‘Would you like a cup of coffee?’

‘Naughty,’ chided Valerie, waving a tan suede finger. ‘I said you must call me Mousie, No, I won’t have a coffee, thank you.’

She didn’t want to have to go to the toilet behind a hawthorn bush mid-morning in front of all the gentry.

They were about to set off when the phone rang loudly in Freddie’s car.

‘’Ullo, Mr Ho Chin, how are fings?’ said Freddie in delight. ‘Grite, grite. Fifty million, did you say? Yeah, that seems about right. Look, ’ave a word with Alfredo and see if ‘e wants to come in too, and phone me back. Yes, I’ll be on this number all day.’

The guns exchanged looks of absolute horror, as Freddie extracted the telephone from the car, all set to bring it with him.

Tony sidled up. ‘D’you mind awfully leaving that thing behind? Might put off the pheasants.’

‘’Course not,’ said Freddie, putting it back in the car. ‘If Chin can’t get me ’ere, he’ll ring my office.’

‘D’you take your telephone hunting too?’ asked an appalled Paul.

‘Always,’ said Freddie.

They started off up an incredibly steep hill behind the house. It was one of those mild January days that give the illusion winter is over. A few dirty suds of traveller’s joy still hung from the trees. No wind ruffled the catkins. It was hellishly hard going. Valerie, wishing she hadn’t worn her long johns, tried not to pant.

As it started to rain, she put up her ginger umbrella which kept catching in the branches. On the brow of the hill the guns took up their position, which they’d drawn out of a hat earlier. Except for Freddie’s distracting red-gold curls, the flat caps along the row were absolutely parallel with the gun barrels. Shooting in the middle of the line between Tony and the Duke, Freddie jumped from foot to foot swinging his gun through the line like Ian Botham hooking.

The Duke, who had three daughters and was hoping for a son so the title wouldn’t pass to a younger brother, was not the only gun looking at Freddie with extreme trepidation.

‘I’m ’ot,’ said Freddie, shedding his Barbour. Seeing the Duke’s and Tony’s looks of horror at Freddie’s red jersey and Bas laughing like a jackass, Valerie, who’d been yakking nonstop to Sarah Stratton about puff-ball skirts, sharply told Freddie to put it back on. For once Freddie ignored her.

Suddenly the patter of rain on the flat caps was joined by the relentless swish of the beaters’ flags.

‘Come on, little birdies,’ cooed Paul, caressing the trigger.

I hate him for being him and not Rupert, thought Sarah despairingly.

A lone pheasant came into view, high over Freddie’s head.

‘Bet he misses,’ said Paul.

The Duke and Tony raised their guns in case he did.

But a shot rang out and the pheasant somersaulted like a gaudy catherine wheel and thudded to the ground.

Next moment a great swarm appeared, some steeply rising, some whirring close to the ground. There was a deafening fusillade and the air was full of feathers as birds cartwheeled and crashed into the grass.

The whistle blew; the first drive was over. Dogs shot off to retrieve the plunder. It was plain from the number of brace being amassed by Freddie’s loader that he’d shot the plus twos off everyone else.

‘Freddie Jones seems a bloody good shot,’ said Bas.

‘Beginner’s luck,’ snapped Paul, who had easily shot the least.

For the next drive the guns formed a ring round a little yellow stone farmhouse with a turquoise door and a moulting Christmas tree in the back yard.

Once more the shots rang out, once more the sky rained pheasants. To left and right, Freddie, the Duke and the Lord-Lieutenant were bringing down everything that came over. Tony fared less well. Valerie was standing behind him with Monica and her endless chatter put him off.

At the end of the drive Tony’s loader, knowing the competitive nature of his boss, pinched a brace from Bas on one side and another from the Lord-Lieutenant who was gazing admiringly at Sarah.

‘Those are mine!’ said the Lord-Lieutenant sharply.

‘Sorry,’ said Tony smoothly. ‘My loader’s very jealous of my reputation.’

‘Jealous loader, indeed,’ muttered the Lord-Lieutenant.

The next drive was a long one, with the guns dotted like waistcoat buttons down the valley. Valerie was bored. Only the birds and the chuckling of a little stream interrupted the quiet. Monica, who found shooting as boring as Corinium Television, was plugged into the Sony Walkman Archie had given her for Christmas. Now she was transfixed by the love duet from Tristan und Isolde, eyes shut, dreamily waving her hands in time to the music and tripping over bramble cables.

Sarah was equally uncommunicative. Weekends were the worst, she reflected, because, knowing Paul was at home, Rupert would never ring. She’d only come out today for something to do. Spring returns, she murmured, looking at the ruby and amethyst haze of the thickening buds, but not my Rupert. He had been so keen, but suddenly after Valerie’s dinner party he had lost interest. Was it Nathalie Perrault, or Cameron Cook, or even Maud O’Hara he was running after now? Perhaps he was just busy and would come back.

A diversion was provided by the arrival of Hermione Hampshire, the Lord-Lieutenant’s wife, who looked like a sheep, had a ringing voice and appeared to be on so many of the same committees as Monica that she even merited having the Walkman turned off.

‘Freddie’s been shooting wonderfully,’ said Monica kindly, and then started rabbiting on to Hermione Hampshire about shooting lunches.

Valerie listened to them. One could pick up lots of tips about pronunciation from the gentry. But it was confusing that Monica said ‘Eyether’ and Hermione said ‘Eether’.

In the next field she was somewhat unnerved by some black and white cows who cavorted skittishly around, startled by the gunfire. She edged closer to Monica and Hermione.

‘D’you know,’ Monica was saying, ‘I never spend less than forty minutes on a cock.’

Valerie was shocked to the core. She’d always imagined Monica was somehow above sex.

‘I agree,’ said Hermione Hampshire in her ringing voice. ‘I never spend less than thirty minutes on a hen.’

‘They’re talking about plucking,’ whispered Sarah with a giggle, ‘and I don’t think either of them have heard of rhyming slang.’

It was the last drive before lunch. Freddie, like a one-man Bofors, was bringing down pheasants with relentless accuracy.

‘Got my eye in now,’ he said, grinning at the Lord-Lieutenant.

He raised his gun as another pheasant flew towards him, then swore as it crashed prematurely to the ground.

‘Sorry,’ said Tony, who couldn’t bear being upstaged a moment longer. ‘Thought you were unloaded.’

This time it was carnage. The air was raining feathers. Dogs circled, loaders went round breaking the necks of the wounded.

Lucky things, thought Sarah. I wish someone would put me out of my misery.

‘I love your dog,’ she said to Henry Hampshire. ‘I saw a beautiful springer the other day with a long tail.’

‘Good God,’ said Henry Hampshire, appalled, and strode off leaving her in mid-sentence.

‘I thought you said you hadn’t shot before,’ said Tony as they walked back to the house.

‘Not pheasant,’ said Freddie, ‘but I was the top marksman at Bisley for two years.’

Entering the garden, they passed two yews cut in the shape of pheasants.

‘You couldn’t even hit those today, could you, Paul?’ said Tony nastily.

After so much open air and exercise, everyone fell on lunch. There was Spanish omelette cut up in small pieces on cocktail sticks, and a huge stew, with baked potatoes, and a winter salad, and plum cake steeped in brandy and Stilton, with masses of claret and sloe gin.

Freddie was in terrific form. His curls had tightened in the rain. Looking more like a naughty cherub than ever, he kept his end of the table in a roar with stories of his army career and his first catastrophic experiences out hunting.

Henry Hampshire, who had a lean face and turned-down eyes, shed his gentle paternalistic smile on everyone, even Sarah.

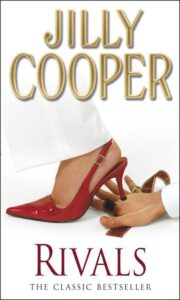

"Rivals" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Rivals". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Rivals" друзьям в соцсетях.