She was beginning to panic that he’d gone for a walk in the wood and fallen down the ravine when she heard an excited squeak from the library. Gertrude had found him, still dressed, passed out cold over his desk. In his hand he still held the pen with which he had been writing his Yeats biography. He had knocked over a glass of whisky which had spilt over the open page of the notebook, blurring the drunken scrawl.

Taggie wrapped a couple of blankets round him, and put a cushion under his head, but he didn’t stir.

He woke six hours later with a debilitating hangover and an even worse sense of foreboding. Staggering groaning into the kitchen, he found Maud reading Anthony Powell upside-down and looking bootfaced. Without being asked, Taggie tore four Alka-Seltzers from their blue and silver metal wrapping and dropped them into a glass. Declan took a gulp, retched and fled from the room.

‘Well,’ said Maud, when he came back, even more white and shaking, ‘what kept you?’

‘I don’t remember,’ growled Declan.

The telephone rang and he clutched his head, groaning. It was the Scorpion, the most seamy of the tabloids. Could they speak to Declan?

‘He’s not here,’ said Taggie quickly.

‘I gather he’s resigned from Corinium. D’you know where I can get hold of him?’

Taggie went pale. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Quite. The press office confirmed it.’

‘No. He’s definitely not here.’ Taggie slammed down the telephone.

Declan glared at her with bloodshot eyes, sensing trouble. ‘What am I supposed to have done?’

Taggie looked nervously at her mother.

‘Come on,’ said Declan.

‘G-given in your notice.’

‘Kerist! Did I really?’

‘You bloody idiot,’ hissed Maud. ‘Ring up Tony at once and apologize. Say you were drunk.’

At that moment Ursula arrived, looking pale from her flu, but very overexcited by events. Joyce Madden had rung her in tears in the middle of the night and told her what had happened.

‘I was just telling Declan to ring Tony and say he’s sorry,’ said Maud. ‘They’re bound to take him back. He’s such a big star.’ The contempt was undeniable.

‘I’m not sure they will,’ sighed Ursula.

‘Sit down,’ said Taggie, pulling out a chair. ‘I’ll make you a cup of tea.’

‘Declan’s got a contract,’ said Maud, ‘and he was far too plastered to put anything in writing last night.’

Ursula turned to Declan who was sitting with his head in his hands.

‘Don’t you remember anything?’

‘I remember a lot of girls in bathing dresses, who were rather ugly, and Rupert dressed up as a horse, and I think I remember having a row with Tony,’ he muttered.

‘You did,’ said Ursula. ‘You gave him an earful. Then you tore up your contract and scattered it all over him and resigned.’

‘Oh Jesus!’ Declan opened a bloodshot eye. ‘Did I really?’

‘And Tony taped the entire conversation, and Joyce Madden transcribed it at once, and no doubt copies are winging their way to the IBA and the ITCA and God knows who else at this moment.’

‘You stupid idiot,’ whispered Maud.

Fear is the parent of cruelty. Having found Declan impossible to live with for the past few months, she had considerable sympathy with Tony. Declan’s career, albeit meteoric, had always been peppered with rows. She was totally unable to appreciate the pressures he’d been under. She proceeded to be blisteringly unsympathetic.

‘Well, I’m not going back,’ said Declan at the end of her tirade.

‘You have no choice. The BBC wouldn’t touch you with a barge pole. You’ll have to crawl for once.’

‘Oh Mummy,’ protested Taggie, putting heavily sweetened, very strong cups of tea in front of Declan and Ursula.

Declan warmed his shaking hands round the mug which had a picture of a girl whose bikini disappeared when the mug was filled with boiling liquid. Like my career, thought Declan.

‘It’s all your fault,’ went on Maud, ‘taking days off to go hunting, going on the bat with Rupert before a programme. You’re like a couple of schoolboys.’

All the animosity she harboured after Rupert had rejected her and embraced Declan seemed to pour forth like scalding lava.

‘I rang up Personnel and resigned too,’ said Ursula importantly. ‘I’m not working for a police state any more.’

Oh Christ, thought Declan, that means I’ll have to pay her salary myself until she gets another job. But he put a hand on her arm.

‘Thanks, darling. That was very loyal of you.’

Everyone jumped as the telephone rang. Maud picked it up. It was the Star. Maud could never resist journalists.

‘We’re a bit hazy this end,’ she said. ‘Declan hasn’t told us anything. What happened?’

The reporter, enchanted by Maud’s soft, caressing tones, told her.

‘I see,’ said Maud grimly. ‘Where’s Rupert?’

‘Well, he arrived in London ten minutes late to chair a seminar on “Alcoholism in the ex-Athlete”. Looked like a prime target, but he refused to comment.’

‘Thanks,’ said Maud. ‘We’ll ring you back when he comes in. How could you?’ She rounded on Declan. ‘Slagging off Tony when you were miked up. I thought you were supposed to be a professional.’

Declan hardly heard her. ‘We’ll have to sell the house,’ he said bleakly.

The telephone rang again. Declan got up and seized the receiver. ‘Will you fucking go away?’ he screamed.

‘Charming,’ said a shrill voice. ‘This is Caitlin, your daughter, if you hadn’t forgotten, and why hasn’t someone come to pick me up?’

‘Oh God,’ said Taggie in anguish, catching the gist. ‘I thought she broke up this afternoon.’

‘Well, you’d better go and get her,’ snapped Maud, who had forgotten to pass on the message.

‘I’m going out,’ said Declan.

‘Whatever for?’ screamed Maud.

‘To do some thinking.’

‘Well, you’d better come up with something pretty quickly. I have no intention of selling this house.’

With four Anadin Extra, four Alka-Seltzers, a cup of strong tea and the remains of last night’s whisky churning uneasily inside him, Declan set out. A mild and sunny day with a gentle breeze had followed yesterday’s torrential rain, freak snow storms and razor-sharp winds. Everything sparkled. For the first time in months the birds ignored Declan’s bird-table and were busy singing and courting in the trees.

Down the Frogsmore, in one day, Spring seemed to have arrived. Primroses nestled on the bank. Coltsfoot exploded sulphur yellow beneath his feet, celandines arched back their shiny yellow petals in the sunshine; even the most uncompromising spiked red blackberry cable was putting out tiny pale-green leaves.

In the fields above, he could see Rupert’s horses pounding round in their New Zealand rugs, tails held high, like children let out of school. In the woods, he found the first anemones and blue and white violets. Far above him the woodpecker was rattling away at a tree trunk. He could almost hear the buds bursting open.

Why the hell had he blown it all in his fucking intellectual arrogance? All he’d had to do was to endure working at Corinium until the end of April, then in the break look around for another job. Now that he’d left in a blaze of drunken publicity with plummeting ratings, no one would want him.

He crushed a wild garlic leaf between his fingers. The smell reminded him of lunches in Soho and endlessly plotting with his cronies to make a better world at the BBC. He’d loved London, but he didn’t want to go back. It was so hot that, on the way home, he took off his coat and sat down on the bank of the stream for a long time, watching the water as it glittered and squirmed with pleasure beneath the sunshine. Gertrude splashed about, and, picking up a stick, bounced up to Declan hoping he’d pull the other end; then, when he wouldn’t, dropped it and licked his face.

An old man, walking his ancient Jack Russell back from Penscombe, stopped for a chat. His grandfather used to be the gamekeeper at The Priory, he said, a hundred years ago, when the land stretched for three hundred acres across the north side of the Penscombe — Chalford Road. He’d kept the place like a new pin. It was sad to see the state it had fallen into, the rotting trees and collapsing walls everywhere. Declan felt ashamed.

‘You can tell Spring’s come at last,’ said the old man, ‘because all the blackbirds are singing.’

But not for me any more, thought Declan in despair.

Then the old man peered closer. ‘Didn’t you used to be Declan O’Hara?’ he said.

By late afternoon Taggie was shattered. Ursula, having parried the press all day, had gone home. After another terrible row with Maud, Declan had barricaded himself into the library, refusing to talk to anyone. Caitlin sat on the kitchen table with her arm round Gertrude, both watching Taggie stuffing a chicken with a mixture of apricots, sausage meat, breadcrumbs and garlic. Used to the central heating and constant chatter of Upland House, Caitlin was shivering like a whippet and gabbling away nonstop.

‘There are going to be no more balls against boys’ schools,’ she announced. ‘Last Friday we danced against Rugborough and one lot of boys took some fifth formers up on the garage roof and they were all smoking and drinking and telling the teachers to fuck off, and Miss Lovett-Standing — think of being saddled with a name like that — the gym mistress, found three condoms in the rhododendrons next morning.

‘I came top in the exam on The Mayor of Casterbridge,’ went on Caitlin. Then, seeing Taggie struggling to understand a recipe for potatoes Lyonnaise, her lips moving slowly as she read, she added kindly, ‘but a sixth former who did the same paper last year told me all the answers beforehand. And two girls in the upper sixth are having abortions this holidays.’

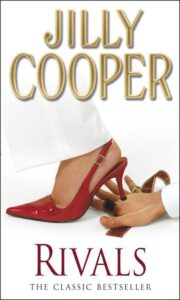

"Rivals" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Rivals". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Rivals" друзьям в соцсетях.