The prospect of making such a fast buck clinched it.

‘Marti Gluckstein’s a crook,’ said Declan in outrage, when Freddie and Rupert jubilantly told him the good news.

‘Don’t be anti-semitic,’ said Rupert primly.

‘And he doesn’t live in the area.’

‘He’s just bought a cottage in Penscombe,’ said Rupert blithely. He was quickly learning he had to box very carefully round Declan’s integrity.

Bearing in mind the IBA’s obsession with minority groups, particularly ethnic ones, Declan, who knew nothing about cricket, recruited Wesley Emerson, a six-foot-five West Indian bowler and the hero of Cotchester Cricket Club, whom he’d met at a Sports Aid drinks party.

Rupert was as outraged as Declan had been about Marti Gluckstein. ‘You’re crazy,’ he yelled. ‘It was only me and the Government stepping in with some very fast talking that stopped Wesley getting busted in New Zealand this winter. He was snorting coke on the pitch, and he’s the biggest letch since Casanova.’

‘I thought that was your prerogative,’ said Declan coldly. ‘Talk about the kettle calling the pot Campbell-Black.’

‘I didn’t realize we were talking about minority gropes,’ snarled back Rupert.

It took all of Freddie’s diplomacy to calm them down.

Basil Baddingham was the easiest of all to recruit. Rupert signed him up as they checked on the edge of a beech covert during the last meet of the season.

‘D’you really want to infuriate Tony?’ asked Rupert.

‘How much?’ said Bas, after Rupert had explained.

‘Ten grand.’

‘Cheap at the price. You’re on,’ said Bas.

Having assembled their Board of the great and the good, Venturer now needed some heavyweight production people. This had to be handled with great delicacy. Anyone worth their salt had already been approached by other consortiums. Two department heads at Yorkshire had just been sacked when it was discovered they’d joined a consortium in the Midlands. Most ITV companies, and the BBC as well, had threatened to boot out anyone found having dealings with any new franchise applicants, even in another area. As Declan was only too aware, Tony was already going through all incoming mail, monitoring telephone calls and checking through desk drawers and wastepaper baskets after dark.

Declan therefore proceeded with extreme caution, winkling out home telephone numbers and promising total anonymity. Early in April he rang Harold White, programme controller at LWT, arguably the most brilliant and innovative brain in television.

‘Harold, it’s Declan.’

‘How extraordinary,’ said Harold. ‘I’ve been trying to get your home telephone number all day. We’re bidding for Granada. You interested in joining our consortium?’

‘Not really, but thanks all the same,’ said Declan. ‘We’ve just moved here, and I couldn’t face another move. How about joining ours?’

One of the pledges that Venturer planned to make to the IBA was that, if they won the franchise, they would take over most of the Corinium staff below board level. But there were three people Declan was anxious to secure for Venturer in advance, in case they were lured away by another consortium.

‘I want Charles Fairburn,’ he told Rupert.

‘He’d fight with the Bishop of Cotchester, the lazy fat poof,’ said Rupert.

‘Charles knows the area like the back of his handbag,’ said Declan, ‘and he’s very bright. He’s just bored out of his skull. I’d move him away from Religious Programming and put him in charge of Documentaries.’

Declan didn’t recognize Charles when he rolled up at The Priory. He was wearing a false nose, a ginger moustache, a ginger felt hat with a Tyrolean feather and dark glasses.

‘Can’t be too careful, dear,’ he said, whisking into the house. ‘James Vereker spent three hours at lunchtime getting his hair streaked yet again, and Tony’s absolutely refusing to believe he didn’t go to an interview.’

Declan was glad he was alone with Charles when he asked him to join Venturer as Head of Documentaries, because Charles promptly burst into tears. For an awful moment Declan thought he’d insulted him.

‘I’m sorry,’ he muttered. ‘I had a feeling you were bored with religion.’

‘I am, I am,’ sobbed Charles. ‘You don’t understand! The absolute bliss of the thought of getting away from Corinium! You’ve no idea how we all miss you.’

It was only then that Declan realized, despite the quips and the jokey exterior, the strain Charles must have been under for years.

‘Tony demoralizes one so much, one feels one will never be good enough to work for anyone else again. I can’t thank you enough, Declan. Do you think there’s any chance of us getting it?’

Declan was touched by the ‘us’.

‘Well, a tenant whose record is good,’ he said, ‘stands a better chance than a new applicant of unknown potential. But Tony’s record isn’t exactly good, and we’re getting together an incredibly strong team. Now if I tell you who they are, will you promise to keep your trap shut, because if one word of this gets out before the applications go in, Tony’ll start tarting up Corinium’s bid and exoceting ours.’

‘Mum’s the word,’ said Charles wiping his eyes. ‘Mummy’s always been the word in fact. I wish you’d met Mummy, Declan. Now, is there anyone else at Corinium you want me to sound out?’

Declan said he was interested in gorgeous Georgie Baines, the Sales Director, and Seb Burrows from the newsroom.

‘Very good choice,’ said Charles approvingly. ‘Both stunningly able. Seb’s in dead trouble. He dug up a terrific story about a bent vet in league with one of Tony’s millionaire farmer friends. Unfortunately he used hidden mikes and secret cameras without getting clearance and, when Tony pulled the programme, Seb handed it over to the BBC. If Seb wasn’t Cameron’s protégé, he’d be out on his ear by now. You’re not interested in her are you? She’s tipped for a BAFTA this week.’

Declan shook his head violently. He hoped that Rupert had forgotten about Cameron.

Rupert rang Declan that evening from London.

‘We need a really good Head of Sport. How about Billy Lloyd-Foxe?’

‘Excellent. I’ve heard nothing but good about Billy,’ said Declan. ‘Will you talk to him?’

The following day Rupert had a drink with his best friend and old show-jumping partner. Billy, who was working for the BBC and very strapped for cash, looked tired and pale. Janey, his journalist wife, had just had another baby; they weren’t getting much sleep at night. He absolutely jumped at Rupert’s proposition, particularly when Rupert offered to treble his salary.

‘You’d have to come back and live in Gloucestershire.’

‘Try and stop me. You know I hate London. Might there be something in it for Janey?’

‘’Course there would,’ said Rupert. ‘How extraordinary we didn’t think of her before. The IBA are dotty about women. She could have her own programme. Those chat shows she did for Yorkshire were terrific. Tell her not to write anything too outrageous in her column before Christmas. We won’t know whether we’ve got the franchise until December.’

‘What happens in the meantime?’ said Billy, who felt guilty that Rupert was buying him large whiskies, and only drinking Perrier himself. ‘I’d adore to join Venturer, but until you can pay me a salary, and the franchise is safely in the bag, I can’t really afford to burn my boats with the Beeb.’

‘It’s all right,’ said Rupert. ‘Georgie Baines, Seb Burrows, Harold White and Charles Fairburn are all in exactly the same boat. All that happens is we attach a strictly confidential memo to our application saying we’ve signed up a Head of Sport, a Sales Director, a Programme Controller, etc., who are all wildly experienced, but for security reasons we can’t reveal their names until we go up to the IBA for the interview in November.’

‘How very cloak and dagger,’ said Billy. ‘I must say it’ll be fun working together again.’

‘We need some more women,’ said Declan. ‘Janey Lloyd-Foxe is gorgeous and talented, but a bit lightweight, and Dame Enid’s almost a man anyway.’

‘I’m going to have a crack at Cameron Cook. I’m working on it,’ said Rupert, who’d already lost twelve pounds in weight.

‘Not safe,’ growled Declan. ‘She’d shop us to Tony.’

Together Freddie and Rupert raised the money.

Rupert, in between his punishing work load as Sports Minister, had several meetings with Henriques Bros, the London Merchant Bank. He found it very difficult not drinking and sticking to his diet over those interminably long lunches, but at least it left him with a clear head. By the second week in April he’d organized a potential seven-million-pound loan.

Freddie’s methods were more direct. He invited half a dozen rich cronies to lunch in his board room and got Taggie up to London to do the cooking. With the boeuf en croute he produced a claret of such vintage and venerability that a one-minute silence was preserved as the first glass was drunk.

‘Christ, that’s good,’ said the Chief Executive of Oxford Motors.

Freddie tipped back his chair, his red-gold curls on end, his merry grey eyes sparkling: ‘I can only afford to drink wine like this once a year,’ he said, ‘but I’d like to be able to drink it every day, and that’s where all you gentlemen come in.’

By the end of lunch, having bandied the names of Marti Gluckstein, Rupert and Declan around the table, Freddie was well on the way to raising the eight million.

Jubilant, he travelled back to Gloucestershire by train and, seeing a plump lady walking down the platform, recognized Lizzie Vereker and whisked her into a first-class carriage. His mood of euphoria, he soon discovered, was matched by Lizzie’s. Thanks to a wonderful new nanny, who seemed impervious to James’s advances, she’d finished and delivered her new novel and the publishers loved it. It was an excuse for her to buy him an enormous drink, she said, but she didn’t know if British Railways stocked Bacardi and Coke.

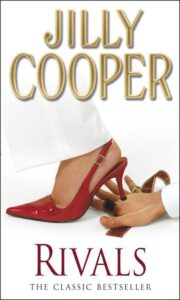

"Rivals" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Rivals". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Rivals" друзьям в соцсетях.