Rupert nearly spilled the champagne he was pouring. ‘How d’you mean?’

‘If you’d been stuck in a studio for twelve hours, you’d worry you’d never see the light again.’

‘Oh, I see,’ said Rupert, relieved. ‘And you’ve got over Cannes?’

‘Almost.’ Cameron took a great slug of champagne. ‘That’s better. D’you know, I was approached by five different groups to join their consortiums?’

‘Very flattering,’ said Rupert, piling smoked salmon onto a roll and handing it to her. ‘Anyone interesting?’

‘Not bad. Unfortunately they’re all pitching against companies like Granada and Yorkshire, who are virtually impregnable, and if Tony got a sniff of it, I’d be out on my ear.’

‘How is he?’ Rupert filled up her glass.

‘Appallingly twitchy. Someone leaked the story of the clipper ship to Dempster, doubling the cost of the party.’

‘Press always get things wrong,’ said Rupert blandly. It was he who had fed the story. He examined his glass of whisky. ‘Has the Corinium application gone in?’ he asked idly.

‘Yes, thank God,’ said Cameron, who was shaking hands with one of the Springer spaniels. ‘Tony’s handing it in to the IBA tomorrow morning.’

Rupert heaved a sigh of relief. If Cameron flipped when he told her about Venturer later tomorrow, at least it would be too late for her to alter Corinium’s application.

Slowly Cameron was taking in the beauty of the room, registering the Romney, the Gainsborough, the Stubbs and the Lely on the pale-yellow walls. Determined not to be impressed, she asked almost too aggressively, ‘How can you possibly live on your own in this great barn?’

‘I don’t,’ said Rupert. ‘I’ve got Mr and Mrs Bodkin who look after me, and the children are often here at weekends, and there’s — er — usually a house guest.’

I asked for that, thought Cameron, biting her lip.

‘Don’t worry.’ Rupert read her thoughts. ‘In order not to besmirch the memory of our last blessed encounter, I’ve been holding my own ever since. I suppose you’ve been sating yourself on Lord B?’

‘Much less than before,’ said Cameron quickly.

The grandfather clock struck midnight.

‘D’you know what day it is now?’ asked Rupert.

‘1st May,’ said Cameron, glancing at her Rolex.

‘D’you know our local poem?’ said Rupert, grinning and putting on a Gloucestershire accent:

First of May, first of May,

Outdoor fucking starts today.

But as usual it do rain.

So we fucks off indoors again.

As he moved towards her he stopped, smiling. ‘Will it be too cold for you outside?’

‘Not if you keep me warm,’ whispered Cameron.

Outside under the moonlit magnolia he took off her clothes, slowly kissing her all over where each garment had been, until she was squirming and helpless with desire. She could feel the dew-drenched lawn under her back. Rupert’s cock was really incredible. As he slid inside her, she felt all the amazed joy of a canal lock suddenly finding it can accommodate the QE2.

When she made love to Tony, she always shut her eyes. She didn’t want to see the uncharacteristically untidy hair, the bulging eyes, the clenched teeth, the veins knotting on his forehead as he came. She liked him sleek and in control. With Rupert she kept her eyes open all the time because he was the stuff of fantasy, and because she didn’t want to miss a second.

Deciding the ground was too hard for her, he later insisted she went on top.

‘You’re so beautiful,’ he said, watching her transported maenad face, ghostly in the moonlight.

Lousy at accepting compliments, Cameron had to joke. ‘Didn’t your mother tell you off for lying on the grass?’

‘I’m not lying,’ said Rupert, arching his back up into her. ‘I’m telling the truth.’

As Cameron opened, so did the heavens.

‘But as usual it do rain,’ murmured Rupert, moving in and out of her. ‘D’you want to fuck off inside again?’

‘Not for ages,’ gasped Cameron. ‘At least it’ll wash off the sweat.’

She woke in Rupert’s huge Jacobean four-poster to find him gone and a note beside the bed saying he was doing a morning surgery at his constituency and would be back around lunchtime.

Looking round the beautiful room with its peachy walls, corn-coloured carpet, yellow-and-pink-striped silk curtains on the four-poster and at the windows, and rose-pink silk chaise-longue, Cameron felt she was waking in the middle of a sunrise. It was an incredibly feminine room for a man. Then she remembered the pale-blue hall and the pale-yellow drawing-room, and decided it must all be Helen’s taste. On the dressing table, amid Rupert’s clutter of betting slips, silver-backed brushes, cigar packets and loose change, were photographs of his children. The girl, exactly like Rupert, had the same arrogant blue-eyed stare; the boy had very dark red hair and large dark wary eyes. Having met Rupert’s pack last night, Cameron felt seven step-dogs might be an easier proposition to take on than two step-children. Helen must have been spectacular to produce kids like that. Mad on sight-seeing, she was plainly a sight herself.

Outside, through a frame of rampant, budding clematis, lay the valley, pale green except for the occasional wild cherry tree in flower, or the blackthorn breaking in white waves over the hedgerows. From an ash grove by the lake she could hear the haunting, sweet cry of the cuckoo. How could Helen have walked out on such a view and such a man?

Having showered and dressed, Cameron went downstairs. The dogs lying in the hall thumped their tails and followed her into the kitchen. There the housekeeper, Mrs Bodkin, was friendly but unfazed by her presence. Perhaps, like people in trains, she could afford to be friendly, knowing Cameron wouldn’t be in situ for long. She mustn’t get jealous and paranoid. Tony was turned on by rows. Rupert, she suspected, would be bored, and walk away from them.

She took some orange juice and coffee out onto the terrace. That must be Declan’s house across the valley, still just visible through the thickening beech wood.

She wondered what he’d been up to since his fall from grace. How strange that on 1st January with Patrick she’d looked across at Rupert’s house and thought, What a kingdom, and now, four months later, here she was.

She stopped only briefly to glance at the library and the first editions, which could be examined at length on a less lovely morning, then set out with the dogs to explore. There was a wonderful untamed beauty, rather like Maud O’Hara, about the garden. Green leaves were uncurling on the tangled old roses, the peacocks and crowing cocks once clipped out of the yew hedges were looking distinctly shaggy. The swimming-pool was full of leaves, the beech hedge round the tennis court was in need of a cut, the lawns dotted with daisies were still lit along the edges by pools of dying daffodils. Rupert and this place need a woman, thought Cameron, to cherish and sort them out.

The stables, on the other hand, were immaculate, and filled with beautiful, well-muscled horses. More horses were out in the fields. The girl grooms treated Cameron with the same we’ve-seen-them-all-come-and-go politeness displayed by Mrs Bodkin.

I’ll show them, thought Cameron, as she set out through the beech woods. I’m the one who’s going to hang in.

The ground was still carpeted with bluebells. Only when she pressed her face close could she distinguish their faint sweet hyacinth scent from the rank sexy stench of the wild garlic. The dogs charged ahead, but the shaggy lurcher called Blue kept bounding back solicitously to check she was all right, shoving his wet nose in her hand, giving her a token lick. It was all so beautiful; she had never felt so happy or so right anywhere.

She had wandered for a mile or two when suddenly she breathed in a sticky, sweet familiar scent that made her tremble. Ahead, a copse of poplars, rising like flaming amber swords, was wafting balsam down the woodland ride towards her, evoking the times she used to inhale Friar’s Balsam under a towel as a child, reminding her all too violently of her mother and Mike. Instantly her euphoria evaporated. She glanced at her watch. It was half past twelve. She must get back. Grey clouds were creeping over the sun; it had become much cooler. She even felt a spot of rain. As she dropped down the wood towards the house an owl hooted. Surely it shouldn’t hoot at midday? Through the trees she could see the lake grey and blank now as a smudged mirror, and as she reached the big lawn she gave a moan of horror. Last night’s deluge had stripped all the petals from the magnolia, scattering them over the grass. Last night’s bride was naked now.

The dogs converged, barking, as a car drew up at the front door. Cameron hoped it was Rupert, but it turned out to be a youth delivering some boxes of T-shirts, who gazed at Cameron in admiration.

‘This is the first lot. Mr C-B wanted them in a hurry,’ he said. ‘Tell him the stickers, the posters and the badges’ll be ready by Monday.’

Cameron couldn’t resist having a look. The T-shirts were a beautiful cerulean blue, with a dark bronze drawing of a boy shading his forehead on the front and the words Support Venturer on the front and the back. They must be for some sporting event. Taking one upstairs, Cameron stripped off and put it on. It fell just below her bush. Suddenly feeling incredibly randy, she hoped Rupert hadn’t got anything planned for the afternoon. As it was much colder, she shut the window, trapping a tendril of clematis which was already wilting and bruised from being trapped on previous occasions. Trying to insinuate its way into Rupert’s bedroom, like her and every other woman, thought Cameron wryly.

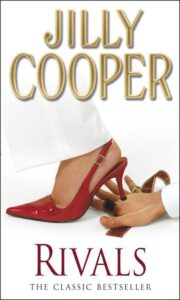

"Rivals" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Rivals". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Rivals" друзьям в соцсетях.