“Seems you are in,” said a high-pitched voice.

He grinned.

“Well, say you’re glad to see us.” j “Come on in,” she said, ‘and shut the door. “

The bed was close to the window so that she could look out. She was old and wrinkled; her white hair was in two plaits and she was propped up by pillows.

“So Mrs. Merret’s off to Australia,” she said.

“Outlandish sort of place. Used to call it Botany Bay. Prisoners went there.”

“That’s in the past, Mrs. Penn,” said James Perrin cheer fully.

“It’s quite different now. Very civilized. After all, we’, were running about in caves at one time … little more than monkeys.”

“You get along with you,” she said and peered at me.

“I liked Mrs. Merret,” she added.

“She listened to what you had to say.”

“I promise to listen,” I said.

“It’s a pity she’s gone.”

“I’m here to take her place. I shall be the one to come and see you now.”

James had brought two chairs from the other side of the room and we sat down.

“You’ll tell all your little grievances to Miss Hammond now,” he said.

“Well,” Mrs. Penn announced, ‘you tell that Mrs. Potteri that I don’t like seed cake. I like a nice jam sandwich . and not jam with pips in it. They get under your teeth. “

I wrote this information down in a notebook which I had brought for the purpose.

“What’s the local news, Mrs. Penn?” asked James and, < turning to me:

“Mrs. Penn is a fount of knowledge. People i come in here and talk to her, don’t they, Mrs. Penn?”

“That’s right. I like to hear what’s going on. There was trouble here last Saturday night. That Sheila …”

“Oh, Sheila?” Once more James turned to me with an explanation.

“That’s Sheila Gentry, in the last of the cottages the one right at the end of the row, I mean. Mrs. Gentry died about nine months ago and Harry Gentry hasn’t got over it yet.”

“He worries too much about that Sheila,” explained Mrs. Penn.

“Mind you, he’s got something to worry about there. She’s got a flighty look about her, that one. And not fifteen yet. I reckon he’ll have a rare to-do with her one day and that day not far distant.”

“Poor Harry Gentry,” said James.

“He’s one of the grooms. Quarters over the stables are full just now, that’s why he’s in one of the cottages. We’ll call, but I hardly think he’ll be there just now.

Well, Mrs. Penn, you’ve met our young lady. “

“She’s a bit young,” said Mrs. Penn, as though I were not there.

“Her youth is not going to affect her ability to do the job, Mrs. Penn.”

Mrs. Penn grunted.

“All right then,” she said.

“Remember, dear, I’ve got my birthday coming along soon and they’ll be sending the cake like they always do from the house. Tell them, no seed. Jam sandwich and no pips in the jam!”

“I will,” I promised.

The door opened and a woman looked in.

“How are you, Mrs. Grace?” asked James.

“Fine, sir. I don’t want to interrupt.”

“It’s perfectly all right. We were just going. Lots to do just now.”

Mrs. Grace came in and was introduced.

“The head gardener’s wife and Mrs. Penn’s daughter-in-law.”

“And you’re Miss Cardingham’s niece. I remember when you came here.”

“I was about thirteen then.”

“And you’re one of us now.”

“I feel that I am.”

“We must be going,” said James, so I shook hands with Mrs. Grace and we left.

I said: “Poor old lady. It must be sad to be bedridden.”

The daughter-in-law looks after her and I think she enjoys being waited on. That’s the Wilburs’ cottage. Dick does carp entering jobs and Mary works in the kitchens so I doubt either of them will be around now. We’ll knock and see. “

We did and he was right.

“That’s old John Greg’s place. He’ll be in his garden, I reckon. He used to work in the gardens until a few years back. He spends all his time now in his own.”

We called and were shown prize roses and vegetables. We were both presented with a cabbage and I was told that the old oak tree in the garden was keeping the sun off some of his herbs. He’d like it trimmed but it was a ladder job and his rheumatics weren’t up to it.

I made a note of this and said I would ask one of the gardeners to look at it.

And so we went on.

There was one I remembered above the others, and that was Sheila Gentry. Her father was working and she was alone in their cottage. She was a very pretty girl with brown curly hair and mischievous eyes. She gave me the impression that she was looking for adventure.

“I expect they’ll find a place for her in the house,” James told me.

“Her mother worked up there when they needed extra help. She was a good pastry cook I believe.”

Sheila let us in and said her father was at work. She took good stock of me, I noticed. She told me she had left school and was keeping house for her father but she didn’t want to do that for ever.

When we left, James said: “You can understand how Harry Gentry’s got his hands full with a girl like that.”

I agreed that I could.

As we came away from the cottages I said, “What about the Lanes’ place?”

“Oh, they’re a case on their own. You know about Flora?”

“Oh yes, I’ve visited her often. Should we look in now?”

“Why not?”

“I feel sure Flora will be there if Lucy isn’t.”

“Mr. St. Aubyn himself looks after them. He has a special interest, you know, because they were his nurses when he was a child.”

“Yes, I know.”

We went through the garden gate. Flora was seated there. She looked a little startled to see us together.

I said: “I’ve come in an official capacity today.”

She looked at me uncomprehendingly.

And almost immediately Lucy came out of the cottage.

“I heard you were taking on the job,” she said.

“You needn’t include us.”

“I know Mr. St. Aubyn takes good care of you,” James told her.

“He does indeed,” Lucy said.

“I wanted you to know that I’m taking Mrs. Merret’s place,” I explained.

“That’s nice,” said Lucy.

“She’s always been such a nice lady, without prying … if you know what I mean.”

I did know what she meant. I had betrayed too much curiosity. I must remember to call when Lucy was not there . just as I had in the past.

James Perrin was very helpful to me during those first days. He made me feel that I was useful, otherwise I might have believed, as I had in the beginning, that there was no real job for me.

James had a small apartment over the estate office. It consisted of three rooms with a kitchen and the necessary facilities. The Merrets’ cottage was being redecorated for a married couple who had been awaiting accommodation.

I soon became very interested in the estate as James initiated me into the working of it, and I could understand why Crispin was so absorbed in it. I would come home and tell Aunt Sophie the fascinating details and she would listen intently.

“All those people working there!” she said.

“Just think! It provides a living for them. And then there are people like old Mrs. Penn who are in their homes for life, looked after by what they call ” the Estate”, which in a way means our Mr. Crispin. He is the great benefactor.”

“Oh yes, he keeps it in working order. Imagine what it was all like before he took over. His father neglected the place and all those people must have been in danger of losing their livelihoods.”

“He has a habit of appearing at the right moment,” said Aunt Sophie soberly.

One day Crispin came into the estate office and saw me sitting at my desk beside James, who was showing me one of the account books.

He called out, “Good morning.” He looked at me.

“All going well?”

“Very well,” replied James.

I said: “Mr. Perrin has been very helpful.”

“Good,” said Crispin and went out.

The next day James and I rode out to one of the farms.

“It’s a question of a faulty roof,” James had said.

“You may as well come. You can meet Mrs. Jennings. It’s your job to be on good terms with the wives.”

On the way we met Crispin again.

“We’re going to Jennings’ farm,” James told him.

“Trouble with a roof.”

“I see,” said Crispin.

“Good day,” and he left us.

It was the following day. I had been down to the cottages to see Mary Wilbur, who had scalded her arm while working in the St. Aubyn kitchen.

Crispin was riding towards me.

“Good morning,” he said.

“How is Mrs. Wilbur?”

“She’s a little shocked,” I answered.

“She has been rather badly scalded.”

“I looked in at the office and Perrin told me where you had gone.”

I was expecting him to ride on but he did not.

Instead he said: “I’d like to know how you are getting on. I was wondering if we might have lunch somewhere together … somewhere we could talk more easily. Would you care to do that?”

I usually brought a sandwich with me and ate it in the office. I could always make myself a cup of tea or coffee in James’s kitchen. James was often out of the office but if he were in he joined me.

I said: “That would be very agreeable.”

“There’s a place I know on the Devizes road. Let’s go that way and you can tell me how things really are.”

I felt elated. There were times when I believed Aunt Sophie’s initial reaction to his offer of a post on the estate was right and that he had done it because he did not want me to go away. My pleasure now was in his interest which occasionally I felt to be there; but at other times I believed my work was necessary and he felt nothing but indifference towards me. But since he had asked me to lunch I did begin to wonder whether there might be a little truth in what Aunt Sophie had thought.

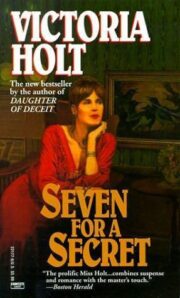

"Seven for a Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Seven for a Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Seven for a Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.