“Of course I know Sloane,” Frank said, which I’d been expecting. “You two are kind of a package deal, right?”

“Yeah,” I said slowly. I realized I hadn’t told anyone about this yet, and didn’t have a practiced explanation. But for whatever reason, I had a feeling that Frank would be willing to wait until I figured it out—maybe because of all the open forums I’d seen him moderate, standing patiently in the auditorium with his microphone while some stoner stumbled through a grievance about the vending machines. “Well . . . she left at the beginning of the summer. I don’t know where she went, or why. But she left me this list. It’s . . .” I stopped again, trying to figure out how to describe it. “It’s this list of thirteen things she wants me to do. And going to the Orchard was one of them.” I glanced back at Frank, expecting him to look confused, or just nod politely before changing the subject. I didn’t not expect him to look thrilled.

“That’s fantastic,” he enthused. “I mean, not that Sloane is gone,” he added quickly. “I’m sorry about that. I just mean that she left you something like this. Do you have it with you?”

“No,” I said, looking over at him, thinking that this should have been obvious, since I was running. “Why is it fantastic?”

“Because there has to be more to it than that, right?” he asked. “It can’t just be the list. There has to be a code, or a secret message . . .”

“I don’t think so,” I said, thinking back to the thirteen items. They had seemed mysterious enough already to me without needing to go looking for extra meanings.

“Will you take a picture and send it to me?” he asked, and I saw he was serious. “If there’s something else in there, I can tell you.”

My first response was to say no—it was incredibly personal, and plus, there were things like Kiss a stranger and Go skinny-dipping on the list, and those seemed much too embarrassing to share with Frank Porter. But what if there was something else? I hadn’t seen anything myself, but that didn’t mean that there wasn’t. Rather than telling him yes or no, I just said, “So I guess you really like puzzles.”

Frank smiled, not seeming embarrassed about this. “Kind of obvious, huh?”

I nodded. “And at the gas station, you practically took over that guy’s word search.”

Frank laughed. “James!” he said. “Good man. I know, it’s a little strange. I’ve been into them for years now—codes, puzzles, patterns. It’s how my brain works, I guess.” I nodded, thinking this was the end of it. I’d shared something, he’d shared something, and now we could go back to running. But a moment later, Frank went on, his voice a little hesitant, “I think it started with the Beatles. My cousin was listening to them a lot, and told me that they had secret codes in their lyrics. And I became obsessed.”

“With codes?” I asked, looking over at him. We weren’t even walking fast any longer. Strolling would probably be the word for what we were doing, just taking our time, walking side by side. “Or the Beatles?”

“Well . . . both,” Frank acknowledged with a smile. “And I got Collins into them too. It was our music when we were kids.” He nodded to the road ahead. “What do you think?” he asked. “Should we try running again?”

I nodded, a little surprised that he wanted to do this, since he’d really seemed to be struggling. But this was Frank Porter. He’d probably be training for a marathon by the end of the summer. We started to run, the pace only slightly slower than what it had been before.

“God,” Frank gasped after we’d been running for another mile or so, “why do people do this? It’s awful and it never gets any easier.”

“Well,” I managed, glancing over at him. I was glad to see that he was red-faced and sweaty, since I was sure I looked much the same. “How much have you been running?”

“Too much,” he gasped.

“No,” I said, taking in a breath while laughing, which made me sound, for an embarrassing moment, like I was choking on air. I tried to turn it into a cough, then asked, “I mean, how long?”

“Never this long,” he said. “This—is too long.”

“No, that’s your problem,” I said, wishing that this could have been a shorter explanation, as I was getting a stitch in my side that felt like someone was stabbing me. “Running actually gets easier the longer distances you cover.”

Frank shook his head. “In a well-ordered universe, that would not be the case.” I looked over at him sharply. He’d said the first part of this with a funny accent, and I wondered if maybe we should stop, that maybe he’d pushed himself too hard for one day. Frank glanced back at me. “It’s Curtis Anderson,” he said.

This name meant nothing to me, and I shook my head. But then I remembered the CD that had slid out from under the passenger seat of his car. “Was that the CD you had the other night?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “The comedian. That’s his catchphrase. . . .” Frank drew in a big, gasping breath. He pointed ahead of us, three houses down. “There’s my house. Race you?”

“Ha ha,” I said, sure that Frank was kidding, but to my surprise, a second later, he picked up his pace, clearly finding reserves of energy somewhere. Not wanting to be outdone—especially since I was supposed to be the expert here—I started to run faster as well. Even though every muscle in my body was protesting it, I started to sprint, catching up with Frank and then passing him, but just barely, stumbling to a stop in front of the house Frank had pointed at.

“Good . . . job,” Frank gasped, bent double, his hands on his knees. Not having the breath to speak at the moment, I gave him a thumbs-up, and then realized what I was doing and lowered my hand immediately.

I straightened up, stretching my arms overhead, and got my first look at the house we’d stopped in front of. “This house is amazing,” I said. It looked like something out of a design magazine—pale gray, and done in a modern style that was pretty unique for the area, which tended to favor traditional, especially colonial-style, houses.

“It’s okay,” Frank said with a shrug.

There was a small sign in front of the house that read, in stylized letters, A Porter & Porter Concept. I nodded to it. “Are those your parents?”

“Yeah,” he said, a little shortly. “My dad’s the architect, my mom decorates.” He said this with a note of finality, and I wondered somehow if I’d overstepped.

“I didn’t know you lived so close to me,” I said. “I’m over on Driftway.” The second I said this, I hoped it hadn’t sounded creepy—like I made it my business to know where Frank Porter lived. But it was a little surprising—I thought I knew most of the kids who lived around me, if only through from the pre-license bus rides we’d all endured together.

“We’ve only been there about a year,” he said with a shrug. “We move a lot.” I just nodded—there was something in Frank’s expression that told me he didn’t want to go into this.

I nodded and unwrapped my earphones from where I’d wound them around my iPod. Frank was home, so clearly our run, unexpected as it was, had come to an end.

“Do it again soon?” Frank asked with a smile, but he was still breathing hard, and I could tell he was kidding.

“Totally,” I said, smiling back at him, so he would know I got the joke. “Anytime.”

I started to put my earbuds back in and noticed Frank was standing still, looking at me, not heading back inside. “Are you going to run back to Driftway?”

“It might be more like a walk,” I admitted. “It’s not that far.”

“Want to come in?” he asked. “I’ll buy you a water.”

“That’s okay,” I said automatically. “Thank you, though.”

Frank shook his head. “Oh, come on,” he said, starting to walk toward the house. After a moment, I followed, falling into step next to him as we walked up the driveway. It was beautifully landscaped, with flowers planted at what seemed to be mathematically precise intervals. He walked around to a side door and reached under the mat for a key, then unlocked the door and held it open for me. I stepped inside a high-ceilinged, light-filled foyer, and had just turned to tell him how nice his house was when I heard the crash.

I froze, and Frank, standing just behind me, stopped as well, his expression wary. “Is—” I started, but that was as far as I got.

“Because this is my project!” I heard a woman screaming. “I was working on it night and day when you were spending all your time in Darien doing god knows what—”

“Don’t talk to me like that!” a man screamed back, matching the woman in volume and intensity. “You would be nowhere without me, just riding on my success—” A woman stalked past us, her face red, before she disappeared from view again, followed by a man, red-faced as well, before he too passed out of view. I recognized them, just vaguely, as Frank’s parents from pictures in the paper and school functions when they were usually standing behind their son, polite and composed and smiling proudly as he received yet another award.

I glanced over at Frank, whose face had turned white. He was looking down at his sneakers, and I felt like I was seeing something I absolutely shouldn’t. And I somehow knew that, however bad this was for him, it was worse because I was there to witness it. “I’m going to go,” I said, my voice barely above a whisper. Frank nodded without looking at me. I backed away, and as I reached the door, I could hear the voices being raised in the other room again.

I let myself out the door and started walking up the driveway, fast, wishing I had just gone home when I’d had the opportunity, and not had to see the expression on Frank’s face as he listened to his parents screaming at each other. I started walking faster once I hit the street, and then broke into a run, despite the fact that every muscle in my body objected to this.

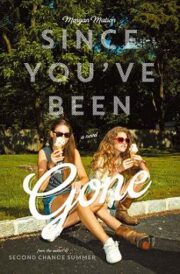

"Since You’ve Been Gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Since You’ve Been Gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Since You’ve Been Gone" друзьям в соцсетях.