I could only see a small patch of sky, the part that was left open between the treetops of the forest around me. The branches seemed like a network that in some places almost obscured the sky. Once my eyes had adjusted to the faint light, I realized that the undergrowth was alive with all manner of things. Tiny orange mushrooms. Moss. Something that looked like coarse white veins on the underside of a leaf. What must be some kind of fungus. Dead beetles. Various kinds of ants. Centipedes. Moths on the backs of leaves.

It seemed strange to be surrounded by so many living things. When I was in Tokyo, I couldn’t help but feel like I was always alone, or occasionally in the company of Sensei. It seemed like the only living things in Tokyo were big like us. But of course, if I really paid attention, there were plenty of other living things surrounding me in the city as well. It was never just the two of us, Sensei and me. Even when we were at the bar, I tended to only take notice of Sensei. But Satoru was always there, along with the usual crowd of familiar faces. And I never really acknowledged that any of them were alive in any way. I never gave any thought to the fact that they were leading the same kind of complicated life as I was.

Toru came back to where I was sitting.

“Tsukiko, everything okay?” he asked as he showed me the handfuls of mushrooms he had collected.

“Totally fine. Really,” I replied.

“Well, I wish you would have come along with us,” Toru said.

“Tsukiko can be a tad bit sentimental.” The instant I realized this was Sensei’s voice, he suddenly and unexpectedly emerged from the shade of the trees just behind me. Whether it was because his suit acted as protective coloring or he was particularly surefooted in the forest, until that moment I had been completely unaware of his presence.

“You were sitting there all alone, lost in your thoughts, weren’t you?” Sensei went on. There were fallen leaves stuck here and there on his tweed jacket.

“Do you mean to say she’s a girlish romantic?” Toru asked as he roared with laughter.

“Girlish, indeed!” I replied, deadpan.

“Well, then, would the young Miss Tsukiko like to help me prepare the soup?” Toru said, reaching into Satoru’s rucksack and taking out an aluminum pot and a portable cooking stove.

“Could you fetch some water?” he asked, and I hurriedly stood up. He told me there was a stream just ahead, so I walked over to find water springing forth among large rocks. Catching some water in my palms, I brought it to my lips. The water was icy cold, yet smooth and mellow. I caught more of it with my palms, bringing it to my lips over and over again.

“HAVE A TASTE,” Satoru said to Sensei, who was sitting up straight, Japanese-style, his feet tucked under his legs on a newspaper that had been spread over the ground. Sensei sipped the mushroom soup.

Satoru and Toru had skillfully prepared the mushrooms they had collected. Toru had cleaned the mushrooms of any dirt or mud, and Satoru had torn the large ones into pieces, leaving the smaller ones as they were, before briefly sautéing them in a small frying pan they had also brought along. Then he put the sautéed mushrooms into the pot of already boiling water, stirred in some miso, and let it all simmer for a little while.

“I studied up a bit last night for our trip,” Sensei said, as he blew on the soup, cupping in both hands the alumite bowl that reminded me of old-fashioned cafeteria ware.

“You studied up? Isn’t that just like a teacher!” Toru responded, heartily slurping his soup.

“There are many more kinds of poisonous mushrooms than I realized,” Sensei said, snaring a piece of mushroom with his chopsticks and popping it in his mouth.

“Hmmm, well…,” Satoru murmured. Having already drained his first bowl, he was just that moment ladling out a second serving.

“The really poisonous ones, you shouldn’t even think about putting them near your mouth.”

“Sensei, please stop! At least while we’re eating,” I pleaded, but he paid no attention to me. As usual.

“But the trouble is, it seems the kaki-shimeji mushroom looks exactly like the matsutake, and the tsukiyotake mushroom is indistinguishable from the shiitake, and so on.”

Sensei’s gravely serious tone caused Satoru and Toru to burst into laughter.

“Sensei, we’ve been collecting mushrooms for more than ten years now, and we’ve never once seen mushrooms as strange as that.”

I now returned my chopsticks, which had been suspended in the air, to my alumite soup bowl. Unsure of whether or not Satoru and Toru had taken notice of my hesitation, I cast a furtive upward glance in their direction, but neither of them seemed to be paying any attention to me.

Satoru and Toru were both mesmerized by Sensei, who had just uttered the statement, “Actually, the woman who used to be my wife once ate a Big Laughing Gym mushroom.”

“What do you mean, ‘the woman who used to be my wife’?”

“I mean my wife who ran off about fifteen years ago,” he said, his voice as serious as ever.

I gave out a little cry. I had assumed that Sensei’s wife had died. I expected Satoru and Toru to be just as surprised, but they both seemed unfazed. As he sipped the rest of his mushroom soup, Sensei told us the following story:

My wife and I often went hiking. We usually hiked smaller mountains, places that were about an hour’s train ride away. Early Sunday mornings, we’d take along a lunch my wife had packed for us and board the train, still empty at that hour. My wife had a book she loved called Suburban Hiking for Pleasure. On its cover, there was a photo of a woman climbing a mountain with a walking stick, wearing leather hiking boots, knickerbockers, and a hat with a feather tucked into it. My wife had re-created this exact outfit—down to the walking stick—and she would wear it on our hiking trips. This is just ordinary hiking, I would say to her, You don’t need to be so formal about it. But she would reply, impervious to me, It’s important to dress the part. She wouldn’t break character, even on a trail where people were walking around in flip-flops. She was a very hardheaded person.

This must have been when our son was in elementary school. The three of us were on one of our usual hiking trips. It was exactly the same time of year as now. It had been raining, and the mountain’s fall foliage was beautiful, although many of the brilliantly colored leaves had been scattered by the rain. I was wearing sneakers and had fallen down a couple of times when they got stuck in the mud. My wife had no trouble walking in her hiking boots. But even when I fell, she refrained from making any sort of sarcastic remark. She may have been stubborn, but she did not go in for cattiness.

After walking for a while, we took a break and each had two honeyed lemon slices. I’m not particularly fond of sour sweets, but my wife insisted that honeyed lemon went together with mountain hiking, so I didn’t bother to argue. Even if I had, I doubt it would have bothered her, perhaps it would just have contributed to the subtle accumulation of anger—the way a succession of smaller waves accumulate into one big wave—that rippled throughout everyday life in unexpected places. That’s just the way married life is, I suppose.

Our son liked lemon even less than I did. He put the honeyed lemon in his mouth and then stood up and walked into a thicket of trees. He liked to pick up autumn leaves from the ground. The boy had a refined sensibility. I followed him to pick up some leaves myself, but when I got closer, I saw that he was stealthily digging a hole in the ground. He hastily dug a shallow hollow, hurriedly spit out the lemon in his mouth, then swiftly filled in the hole with dirt. That’s how much he disliked lemon. He wasn’t the kind of child who wasted food either. My wife had raised him well.

You must really hate it, I said to him. He was a bit startled, but then nodded silently. I’m not very fond of it either, I said, and he smiled with relief. Our son looked a lot like my wife when he smiled. He still looks a lot like her. Come to think of it, he will soon be fifty years old, the same age my wife was when she ran off.

The two of us were crouched over, busying ourselves with collecting autumn leaves when my wife walked up. Even though she was wearing those huge hiking boots, she didn’t make a sound. Hey there, she said behind our backs, and we both flinched with surprise. Look what I found—a Big Laughing Gym mushroom, she whispered in our ears.

THE FOUR OF us had quickly finished what had seemed like plenty of mushroom soup. The combined varieties of mushrooms had mingled together and the taste was ineffable. That had been Sensei’s description—“ineffable.” In the middle of his story, he had abruptly interrupted himself to say, “Satoru, the soup’s aroma is simply ineffable.”

Satoru rolled his eyes, and Toru said, “Sensei, you sound just like a teacher!” They urged Sensei to continue the story. What happened with the Big Laughing Gym? Satoru asked, while Toru wondered, How did she know it was a Big Laughing Gym?

Besides Suburban Hiking for Pleasure, my wife had another favorite book, a little field guide to mushroom identification, like a mushroom encyclopedia—these two books were always tucked away in her rucksack whenever we went hiking. And, now, she had the guide open to the page on Big Laughing Gym mushrooms, and she kept repeating, This is it! This is definitely that kind of mushroom!

“Fine, you know it’s a Big Laughing Gym, but what are you going to do with it?” I asked her.

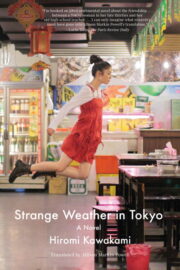

"Strange Weather in Tokyo" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strange Weather in Tokyo" друзьям в соцсетях.