Her son snuggled closer to her, his head tight against her thighs.

“He’s the lucky one,” Larry said.

Again she seemed embarrassed. She glanced down quickly, seemed undecided whether to push the boy away from her body or pull him closer. Her lashes fluttered and Larry couldn’t tell whether she had consciously maneuvered them or whether she was truly as bewildered as she appeared.

He suddenly wondered if she had suspected any double entendre in his words, and he quickly explained, “He’s nice and warm,” and then just as suddenly realized he had fully intended a double meaning.

Mothers were appearing in the streets now. Storm doors clicked shut behind them, and they stepped into the well-ordered streets of the development, wearily leading their charges off to another day of school. They descended on the bus stop, and Margaret began talking with them, and he noticed an instant change in her attitude, a lighter tone in her voice, a smile that was forced and not so genuine as her earlier smile had been. And then the big yellow school bus rumbled around the corner and ground to a stop, and the doors snapped open, and the little boys fought for first place in the line, and one of the little girls squeaked, “Ladies first, ladies first!” and Chris ran to him and planted a cold, moist kiss on his cheek and then scrambled aboard the bus, and he was aware all at once of the fact that he had not shaved. The women began to disperse almost before the bus got under way. He waved at Chris and then turned.

“Well,” he said to Margaret, “so long.”

She nodded briefly, smiling, and he turned and walked back to the house.

In two days’ time, the walls of his office were covered with sketches.

The room was a small one, the smallest in the house, a perfect eleven-by-eleven square. The wall opposite the door carried a bank of windows which rose from shoulder level to the ceiling. A good northern light came through the windows even though the blank side of a split-level was visible not fifteen feet away.

The room was devoid of all furniture save his drawing board, a stool, a filing cabinet for blueprints, and a filing cabinet for correspondence. A fluorescent lamp on a swinging arm hung over the drawing board for use on days when the natural light was insufficient.

The drawing board was large, a three-by-four-foot rectangle set up against the window wall. Thick tan detail paper had been stapled to its wooden surface. He liked to work in an orderly fashion, and so the board was uncluttered except for the tools he considered essential to his trade. These were a box of mechanical pencils, a second box containing leads of different hardness (H and 2H were the ones he used most frequently), a T square hanging on a cup hook at the right of the board, a scale, a ruby eraser and the item he considered indispensable: an erasing shield. Rolls of tracing paper in various widths — twelve inch, twenty-four inch, and thirty inch — lay on top of the flat green surface of the blueprint cabinet together with his typewriter, a portable machine which had seen better days.

He had used the typewriter when he’d first begun the Altar job listing an outline of requirements for each room. He had not concerned himself with general requirements. These he retained in his memory and there was no need for a typewritten reminder. At the same time, the notes — while being detailed — did not consider such specifics as furniture sizes, which he knew by heart and which automatically came to mind when he was considering the size of any room.

The notes then, detailed but not specific, looked like this:

STUDY — MOST IMPORTANT ROOM IN HOUSE! Desires open view and feeling of spaciousness. Does not like to work near walls. Desk unsurrounded. Space for many books. Would like balcony overlooking short view as opposed to longer open view from desk. Exposure irrelevant, but not looking into sun. Works from ten in morning to four in afternoon generally. Does not want look or feel of an office, needs area here for small refrigerator and hot plate as well as space for hidden filing cabinets. These for correspondence and carbon copies of manuscripts. Desk will be large. Other furniture: slop table, sofa, bar.

BEDROOM — Sleep two people. View unnecessary. Likes to wake to morning sun. Fifteen square feet closet space. Accessibility to study. Balcony if possible. (Tie-in to study balcony?) No need for...

The notes went on in similar fashion for each room in the house. There was a time when Larry, fresh out of Pratt Institute and beginning practice, would have made a flow diagram of the proposed house. The diagram would have been a simple series of circles, each representing an area, and its purpose would have been to define the relationship between the areas. He still used a mental flow diagram, but he no longer found it necessary to commit such elementary planning to paper. Unless, of course, he were working on something with as many elements as a hospital. A house rarely contained more than ten or twelve elements, and these he safely juggled in his mind.

With most houses, Larry found it best to begin his thinking with an over-all theme which came from the client. These, capitalized in his mind, were necessities or concepts like Ideal Orientation, Maximum Economy, Soar Heavenward, Cloistered Silence and the like. Roger Altar wanted to spend seventy-five thousand dollars on his house, and he had given Larry a virtual carte blanche. Unstrapped economically, unlimited architecturally, he had only to concern himself with expression, and so his early thoughts about the house did not consider the economical placing of toilets back to back but only the type of statement he wanted in the house: Powerful? Dramatic? Natural? In short, he asked himself what kind of an experience the house would be and, thinking in this manner, he began by drawing perspectives first rather than floor plans.

Would Altar accept all spaces in one space?

Or would he prefer a different experience for the living spaces as opposed to the bedroom spaces?

Or should the house be a tower rather than a low horizontal?

Would Altar prefer something more serene, a scheme of sunken courts?

Using the yellow tracing paper, he allowed his mind to roam, creating the doodles of free expression. Would Altar consider a cube on stilts? The land sloped sharply. Should he take advantage of the slope the way Wright would do; or should he fight it, present the house as a statement against the terrain, like Corbusier?

He did not discard any of his sketches. By Wednesday morning, they were all Scotch-taped to the walls of his office and, like a connoisseur at a gallery exhibit, he stood in the center of the small room and studied them carefully. He would not show Altar all of the sketches. He would eliminate those he disliked and then work over the remainder into ⅛″ scale drawings. These exploratory sketches would be presented to Altar for thought and comment. Once they had decided on an approach, he would then attack his preliminary drawings, using white paper rather than the rough tracing paper.

The weeding-out was not a simple job. He worked all through the morning and then went into the kitchen for lunch. He felt the need for a short break after lunch and so he drove up to the shopping center to buy the afternoon newspaper. He did not expect to see Margaret Gault, nor was he looking for her.

Mrs. Garandi the widowed old lady who lived with her son and daughter-in-law in the house across the street, was coming out of the super market with a shopping bag. Larry tucked his newspaper under his arm and then walked quickly to her.

“Can I help you with that, Signora?” he asked.

Mrs. Garandi looked up, surprised. She was a hardy woman with white hair and the compact body of a tree stump. She had been born in Basilico, and despite the fact that she spoke English without a trace of accent, everyone in the neighborhood called her Signora. There was no attempt at sarcasm in their affectionate title. She was a lady through and through.

Larry’s fancy, in fact, maintained that the Signora had been high-born in Italy and had learned English from a governess at the same time she’d learned to ride and serve tea. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Mrs. Garandi had been born in poverty, married in poverty, and had come to America with her husband to seek a new life. She knew she couldn’t start with a language handicap and so she’d instantly enrolled at night school, where she’d learned her flawless English.

“Oh, Larry,” she said, “don’t bother. It’s not heavy.”

“It’s no bother. Where’s the car?”

“I walked.”

“Well, come on, I’ll drive you home.”

“Thank you,” she said. “I am a little tired.”

He took the shopping bag from her and together they walked to the car. He closed the door behind her and then went around to the driver’s side. When he was seated, he said, “Whoo! Cold!”

“Terrible, terrible. Do you really think it’ll snow?”

“Is it supposed to?”

“The radio said so.”

“Today?”

“Supposed to come this afternoon.”

“I don’t believe it,” he said. “The sky is clear.”

He started the car and backed out of his space. He was slowing down at the exit when he saw Margaret.

She walked with her head bent against the wind, one hand in her coat pocket. Her right hand held her lifted coat collar, and her cheek was turned into the collar. He tooted the horn, and she looked up instantly, recognized him, and waved. He waved back. Margaret walked closer to the car. She was saying something but he couldn’t hear her because the window was closed.

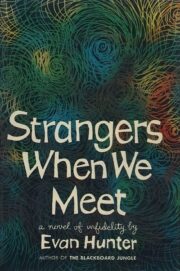

"Strangers When We Meet" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strangers When We Meet". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strangers When We Meet" друзьям в соцсетях.