“Today. Why?”

“I’m almost out of shirts.”

“Again? Why don’t you buy a few more? A man could get neurotic worrying over whether his shirts will last the week.”

“Maybe I’ll get some today, after I’m through with this character.”

“You say you will, but you won’t. Why do you hate to buy clothes?”

“I love to buy clothes,” Larry said. He grinned. “I just hate to spend money.” He drank his orange juice. “Good stuff.”

“They had a sale at Food Fair.”

“Good. Better than the stuff you had last week.”

“You look handsome, Dad,” David said.

“Thank you, eat your egg, son.”

“You’ll have to take Chris to the bus stop this morning,” Eve said. “I’m not dressed.”

“Are you going to the Governor’s Ball, or are you dropping your son off at the school bus?”

“I’m doing neither. You’re dropping him off.”

“A mother’s job...”

“Larry. I can’t go in my underwear! Now don’t—”

“Why not? That would set lovely Pinecrest Manor on its ear.”

“You’d like that.”

“So would all the other men in the development.”

“That’s all you ever think of,” Eve said.

“What’s all he ever thinks of?” Chris asked. He shoved his cup aside. “I finished my egg.”

“Go wash your face,” Eve said.

“Sure.” Chris pushed his chair back. “But what’s all he thinks of?”

“S-e-x,” Eve spelled.

“What’s that?”

“That’s corrupting the morals of a minor,” Larry said. “Go wash your face.

“Is s-e-x Santa Claus?” Chris asked.

“In a way,” Larry answered, smiling.

“I could tell,” Chris said triumphantly. “Because everytime you spell, it’s Santa Claus.”

“Is it almost Christmas?” David asked.

“Come on, come on,” Larry said, suddenly galvanized, reaching for his coffee cup. “Wash your face, Chris. Hurry.”

Chris vanished.

“You’re not having cereal?” Eve asked.

“I don’t want to stuff myself. I’m meeting this guy for breakfast.”

“You’ll never gain any weight the way you eat.”

“Who wants to? A hundred and ninety-two pounds is fine.”

“You’re six-one,” she said, studying him as if for the first time. “You can use a few pounds.”

Larry shoved back his chair. “Chris! Let’s go!”

Chris burst out of the bathroom. “Am I all right, Ma?” he asked.

“You’re fine. Put on a sweater.”

Chris ran to his room. Larry took Eve in his arms.

“Be good. Don’t make eyes at the laundry man.”

“He’s very handsome. He looks like Gregory Peck.”

“Did you brush your teeth?”

“Yes.”

“Do I get a kiss now?”

“Sure.”

They were kissing when Chris came back into the kitchen. The moment he saw them in embrace, he began singing, “Love and marriage, love and—”

“Shut up, runt,” Larry said. He broke away from Eve. “I’ll call you later.”

They went out of the house together. David and Eve stood in the doorway, watching. “When I get big next week, can I go with them?” David asked.

“First you’ve got to stop wetting the bed,” Eve said absently.

From the car Chris yelled, “Bye, Ma!”

Larry waved and backed the car out of the driveway, glancing at the line of his small development house and hating for the hundredth time the aesthetic of it. Pinecrest Manor, he thought. Lovely Pinecrest Manor. His wrist watch read 7:50. He waved again when they turned the corner. The bus stop was five blocks away on the main road which hemmed in the development. He pulled up at the intersection and opened the door for Chris. “Have fun,” he said.

“Yeah, yeah,” Chris said, and he went to join the knot of children and mothers who stood near the curb. Larry watched him, proud of his son, forgetting for the moment that he had to catch a train.

And then he saw the woman, her head in profile against the gray sky, pale-blonde hair and brown eyes, her head erect against the backdrop of gray. She held the hand of a blond boy, and Larry looked at the boy and then at the woman again. One of the other women in the group, one of Eve’s friends, caught his eye and waved at him. He waved back, hesitating before he set the car in motion. He looked at his watch. 7:55. He would have one hell of a race to the station. He turned the corner onto the main road, looking back once more at the pale blonde.

She did not return his glance.

The man’s name was Roger Altar.

“I’m a writer,” he said to Larry.

Larry sat opposite him at the restaurant table. There was something honest about meeting a man for late breakfast. Neither of the two had yet buckled on the armor of society. The visors had not yet been clanged shut, concealing the eyes. They sat across from each other, and there was the smell of coffee and fried bacon at the table, and Larry made up his mind that all business deals should be concluded at breakfast when men could be honest with each other.

“Go ahead, say it,” Altar said.

“Say what?”

“That you’ve always wanted to be a writer.”

“Why should I say that?”

“It’s what everyone says.” Altar shrugged massive shoulders. A waitress passed, and his eyes followed her progression across the room.

Larry poked his fork into the egg yolk, watching the bright yellow spread. “I’m sorry to disappoint you,” he said, “but I never entertained the thought. As a matter of fact, I always wanted to be exactly what I am.”

“And what’s that?”

“The best architect in the world.”

Altar chuckled as if he begrudged humor in another man. But at the same time, the chuckle was a delighted release from somewhere deep within his barrel chest. “I enjoy modesty,” he said. “I think I like you.” He picked up his coffee cup with two hands, the way Larry imagined medieval kings might have. “Do you like me?”

“I don’t know you yet.”

“How long does it take? I’m not asking you to marry me.”

“I’d have to refuse,” Larry said.

Altar exploded into real laughter this time. He was a big man wearing a bulky tweed jacket which emphasized his hugeness. He had shaggy black brows and hair, and his nose honestly advertized the fact that it had once been broken. His chin was cleft, a dishonest chin in that it was molded along perfect classical lines in an otherwise craggy, disorganized face. But there was nothing dishonest about Altar’s eyes. They were a sharp, penetrating brown, and they seemed to examine every object in the room while miraculously remaining fixed on the abundant buttocks of the waitress.

“It’s a pleasure to talk to a creator,” Altar said. “Are you really a good architect, or is the ego a big bluff?”

“Are you really a good writer, or is the ego a big bluff?” Larry asked.

“I try,” Altar said simply. “Somebody told me you were honest. He also said you were a good architect. That’s why I contacted you. I want someone who’ll design a house for me the way he wants to design it, without any of my half-assed opinions. If I could design it myself, I would. I can’t.”

“Suppose my ideas don’t jibe with yours?”

“Our ideas don’t have to jibe. Only our frame of reference. That’s why I wanted to meet you.”

“And you think a breakfast conversation is going to tell you what I’m like?”

“Probably not. Do you mind if I ask a few questions?” He snapped his fingers impatiently for the waitress. “I want more coffee.”

“Go ahead. Ask your questions.”

“You’d never heard of me before I called, had you?”

“Should I have?”

“Well,” Altar said wearily, “I’ve achieved a small degree of fame.”

The waitress came to the table. “Will there be anything else, sir?” she asked.

“Two more coffees,” Altar said.

“What have you written?” Larry asked.

“You must be abysmally ignorant,” Altar said, watching the waitress as she moved away from the table.

Larry shrugged. “If you’re shy, don’t tell me.”

“I wrote two books,” Altar said. “The first was called Star Reach. It was serialized in Good Housekeeping and was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. We sold a hundred and fifty thousand copies in the hard cover and over a million in the paperback. Ray Milland starred in the movie. Perhaps you saw it last year?”

“No, I’m sorry. What was the second book?”

“The Debacle,” Altar said. “It was published last June.”

“That’s a dangerous title,” Larry said. “I can see a review starting with ‘This book is aptly titled.’”

“One started exactly that way,” Altar said, unsmiling.

“Was this one serialized?”

“Ladies’ Home Journal,” Altar said. “And Literary Guild, and Metro bought it from the galleys. They’re making the movie now.”

“I see. I guess you’re successful.”

“I’m King Midas.”

“Well, in any case, I haven’t read either of your books. I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be. We can’t expect to enlighten everyone with two brilliant thrusts.”

“Jesus, you’re almost insufferable,” Larry said, laughing. “Will you get me a copy of The Debacle? I’m assuming that’s the better of the two.”

“If it weren’t, I’d quit writing tomorrow.”

“Will you get it for me?”

“Go buy one,” Altar said. “I run a grocery store, and I don’t give away canned goods. It sells for three-ninety-five. If you’re cheap, wait until next June. It’ll be reprinted by then, and it’ll only cost you thirty-five cents.”

“I’ll buy one now. It may break me, but I’ll buy it. How much do you want to spend on this house of yours?”

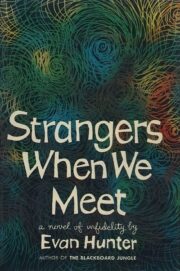

"Strangers When We Meet" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strangers When We Meet". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strangers When We Meet" друзьям в соцсетях.