“Thanks.”

“It was too tight for you, you know,” Lois said. “It made you look like all ass.”

“Sometimes I think I am,” Linda said.

Disgustedly, she extended one leg and began putting on the stockings.

It seemed to her that everything, sooner or later, passed into the no man’s land of community property. She could count on the fingers of one hand the possessions which she could call exclusively, inviolately her own. The rest of the accouterments of everyday living were shared equally within the corporate structure of sisterhood and twinship. There were only three things she truly owned and these were jealously coveted in an old tin candy box at the back of the second dresser drawer.

The first of these was a pink shell as exquisitely turned as a water nymph’s ear.

She had found it one summer at Easthampton while walking alone on the shore, just before a storm. She was nine years old, and she watched the sky turn ominously black and the waves beating the sand in windswept anger. When she found the shell, she picked it up and held it cradled in the palm of her hand; it was a delicate thing, the pink luminescent against the gathering fury of the storm. The thunder clouds broke around her. Barefoot, her hair and her skirts flying, she had run back to the cottage across the suddenly wet sand, the shell clutched in her small fist.

The second possession was an autumn leaf, thin and fragile, carefully mounted with Scotch tape on a piece of stiff paper, losing its structure nonetheless, so that only the tracery of delicate veins remained in some spots.

She had been eleven when the leaf fell.

She had been sitting alone on a bench in the park across the street from her apartment building, her black hair pulled back into a pony tail, an open book in her lap, her wide blue eyes full with the lyrics of Edna St. Vincent Millay. It had been a quiet day, wood smoke still with the splendor of fall. She had sat alone with her book of verse and read:

Silver bark of beech, and sallow

Bark of yellow birch and yellow

Twig of willow.

Stripe of green in moosewood...

The leaf fell.

It spiraled silently on the still air to settle on the open page of the book. Yellow and brown, it lay on the open page, rustled as if to flee, settled again when she covered it with her hand. For no reason, her eyes suddenly brimmed with tears. She had taken the leaf home and mounted it.

The third possession in the candy tin at the back of the second dresser drawer was an Adlai Stevenson campaign button.

These were her own.

Everything else she shared with Lois; even her face and her body. She did not resent the sharing as persistently as she had long ago, but just as strongly. All she wanted to be, she supposed, was Linda Harder. And the chance division of a cell had made that the most difficult aspiration in the world.

In the beginning, of course, she had not known.

There was Mama, and Daddy, and Eve, and Lois. Lois seemed to be just another person, as different from Linda and everyone else as she could possibly be. They were sisters. Just the way she and Eve were sisters.

After a while it became apparent that she and Lois were somehow special. She had never been able to understand why Mrs. Harder dressed them alike. Why didn’t she dress Lois and Eve alike? Eve was a sister in the family, too, wasn’t she? She began to wonder about it. And she began to hear an oft-repeated expression: “Oh, how cute! Are they twins?”

One day she went to Mrs. Harder and asked, “What’s twins?”

“You and Lois are twins, darling,” Mrs. Harder said.

“I know, but what’s twins?”

“That means you were born together. You look alike.”

“Were Eve and me born together?”

“No, darling.”

“Well, we look alike.”

“But not exactly alike. You and Lois are identical twins. That means you look exactly alike.”

Linda pondered this for a grave moment. Then she said, “I don’t want to look exactly like nobody but me.”

And even though Mrs. Harder had laughed and said something about both her girls being adorable little darlings, Linda was not pleased at all.

After that, whenever anyone mistakenly called her “Lois,” she would whirl angrily and say, “I’m Linda!”

She did not enjoy the confusion their sameness bred. She did not smile when her nursery-school teacher reported, “One of your girls was very naughty today, Mrs. Harder. I can’t remember which one. They’re so hard to tell apart.”

She did not appreciate other children referring to her and Lois as “Harder One” and “Harder Two.” To one of these children, she angrily replied, “I’m not a number. I’m Linda!”

Nor did she enjoy the constant comparison.

“Well, Linda doesn’t draw as well as Lois, but she likes to work with clay.”

“No, Lois is the one who tells the stories. Linda’s a little shy.”

“You can tell if you really look closely. Linda’s hair isn’t as glossy.”

“Now eat your cauliflower, Linda! See how nicely Lois is eating?”

It took her a long while to learn that there were compensations for loss of identity.

There was, to begin with, the protective coloration of the pack. Both girls, she discovered, could raise holy hell together and get away with it, simply because it was considered adorably cute in tandem. Both girls could utter completely stupid inanities which were considered terribly advanced and grown up, simply because they were spoken by twins. At any party, the Harder twins — dressed exactly alike, their black-banged hair sleekly brushed, their blue eyes sparkling beneath long black lashes, their petticoats stiffly rustling — stole the show from the moment they entered. There was sanctuary and notoriety in twinship.

But most important of all, there was companionship.

There was no such thing as a lonely rainy day indoors, no such thing as a long solitary bout with the whooping cough or the mumps. Lois was constantly by her side, an ally and a friend. It was not so bad being a twin at all.

Except sometimes, when you remembered sitting alone on a park bench, alone, Linda Harder.

When you remembered the fall of a solitary leaf.

At eight-twenty, when Linda came out of the bedroom, Hank MacLean was sitting in the living room talking to her parents. He was a tall boy with sandy brown hair and dark brown eyes. He wore a gray tweed suit and a blue tie, and he rose instantly when Linda entered the room.

“You look pretty,” he said.

“Thank you. Was Dad telling you how tough business is?”

“As a matter of fact,” Hank said, “I was telling him about fencing.”

“I didn’t know he was on the fencing team, Linda,” Mr. Harder said.

“The second team, Mr. Harder,” Hank corrected. “That means I only get to stab people every now and then.”

Mr. Harder chuckled. Mrs. Harder inspected her daughter and said, “You look very lovely, darling.”

“Thank you. Shall we go, Hank?”

“Sure. If you’re ready.”

Linda kissed her parents and then walked to the closet. “Is it cold out?” she asked. “Do I need something for my head?”

“It’s just brisk,” Hank said.

She took her coat from a hanger, and he helped her on with it. She felt rather strange. She always did when she was dating one of Lois’s cast-offs. She had the feeling that, having failed with his first choice, he was now dating a mildly reasonable facsimile of the original. Invariably, boys who expected a carbon copy of Lois were disappointed. She did not know Hank at all, except that he had dated Lois several times and then suddenly called Linda one day last week. But she couldn’t shake the feeling that she was second choice, second best, and she remembered him helping Lois into her coat just two short weeks ago, and the memory was painful.

“I didn’t know whether you and your sister would be dressing alike,” he said. She turned, puzzled, buttoning her coat. “Even though you’re not going out together, I think it’s nice for people to know you apart, don’t you?”

“What?” she said, thoroughly puzzled.

He lifted a box from the hall table. “This is for your buttonhole,” he said. “So I’ll know you when we meet at the out-of-town newspaper stand.”

She was too surprised to speak. She lifted the lid from the box, parted the green paper, and then picked up the corsage.

“I guess roses go with everything,” he said. “I hope.”

“This... this was very thoughtful, Hank,” she said. “Would you help me pin it?”

“I’m only on the second team!” he said, backing away from the pins.

Linda laughed. “Mom?” she said, and Mrs. Harder came to pin the corsage.

“There,” she said. “That’s a beautiful corsage. You look lovely, Linda.”

Hank nodded. He didn’t say anything. He simply nodded, and Linda saw the nod and the strange sort of pride in his eyes, and she looped her hand through his arm suddenly.

“Not too late, Hank, please,” Mrs. Harder said. “This is a weekday.”

“Okay,” he answered. “Good night, Mr. Harder.”

“G’night,” Mr. Harder said from the living room.

From the bedroom, Lois called, “Have fun, Lindy! Hi, Hank!”

“Hi,” Hank called back.

Gently, he loosened Linda’s hand from his sleeve and captured it with his own.

13

On Thursday night, in the darkness of the parked automobile, Larry sat and waited.

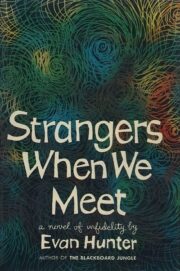

"Strangers When We Meet" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strangers When We Meet". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strangers When We Meet" друзьям в соцсетях.