“I’d appreciate it,” Larry said.

Baxter jotted a reminder onto his memo pad. “Will there be an enclosure problem without those doors?”

“I don’t think so. We won’t have to worry about heat because they’ll be working during the summer. And tar paper should keep out the elements.”

“Your house’ll be ready in September. I guarantee it.”

Larry laughed.

“Don’t laugh,” Baxter said. “You don’t know Di Labbia. The man’s a demon on the job. Perhaps you met him over a cocktail where he looks like something out of The Barretts of Wimpole Street, but have you ever seen him with a hammer in his hands? He works like ten men, and he demands the same performance from his crew. This is a real builder. You don’t find them like him any more.”

“He underbid by about five thousand,” Larry said.

“Perhaps not. He’s thorough, but fast. He doesn’t get into those costly months of men piddling around doing nothing. When his men are on the job, there’s work to be done. He sees to it that they do it, and then gets them out quick. Larry, he’s a businessman. He knows the mortgage holding company will give him a quarter of his money at roofing and rough enclosure, and another quarter when his brown plastering is done. He gets his next payment when he’s fully plastered and has his heating unit completed. His final payment doesn’t come until C. of O. So why should he fool around? He wants to build and get out. If he bid five thousand lower than the next closest bid, it’s because he can damn well do it for five thousand lower. He’s organized and smart. I tell you Altar will move into that house in September. I know Di Labbia.”

“Okay,” Larry said, smiling. “I’ll take your word for it.”

“I’m not just making talk about Di Labbia,” Baxter said. “I’m a businessman myself. You may remember my telling you that.”

“I remember.”

“I’m lucky because I’m in a business I like, and also because I feel it’s a worth-while one. Suppose, for example, that I made ten million dollars a year manufacturing plastic practical jokes? I’d feel like a pimp.”

Larry burst out laughing.

“He laughs,” Baxter said. “There are men who do that for a living, Larry. When they die, they’ve left a plastic practical-joke empire built on Japanese labor. Maybe some Japanese factory town will erect a statue to the beloved departed benefactor. I doubt it. We’re dealing in essentials, you and I, basics. Architecture is a noble profession, and I’m proud to be a part of it. But at the same time, it’s my livelihood, and I’m forced to look at it cold-bloodedly every now and then. Which is why I’m concerned with when Di Labbia finishes that house. I’m not at all interested in Di Labbia, and even less interested in Roger Altar. I’m interested in you.”

“Me? I don’t understand.”

“Your direction, your goals. Are you happy doing private residential work? Because if you are, I’ve no right to interfere. But the job you turned in on the Puerto Rican development was superb. Building will begin as soon as we’ve completed the scheme. I was going to ask you to do that for us, but something else has come along. Larry, I’d be interested in knowing—”

There was a discreet knock on the door.

“Come in,” Baxter said.

The door opened, and a tall brunette came into the room carrying a tray upon which were the coffee cups and the English muffins.

“Ah, Nancy,” Baxter said. “Just put it down anywhere on my desk.”

Nancy moved aside some papers, slid some tile samples to the corner of the desk, and then put down the tray.

“Mr. Fandella called about five minutes ago,” she said. “I told him you were in conference. He asked that you call him sometime this afternoon.”

“Thank you.”

“You still don’t want to take any calls?”

“Not until Mr. Cole leaves.”

Nancy smiled at Larry and then walked out of the room. She was a very attractive girl who walked with certain knowledge of her quiet good looks.

When she was gone, Baxter said, “I like to surround myself with pretty people. It’s absurd, I know, but I have to look at my staff for from eight to sixteen hours a day. Take your coffee.” He handed Larry a cup and then picked up his own cup of black coffee. “Toasted English? There’s some jam here.”

“Thanks,” Larry said. He walked to the desk, picked up one of the muffins and spread it with jam.

“Eloise objected at first. She didn’t see why every secretary or receptionist I hired had to be pretty. I explained to her that it was all her fault.”

“How so?”

“She’d set such a high aesthetic standard at home that she’d spoiled me!” Baxter began chuckling. “She’s an angel, that woman. I love her.” He chuckled again. “She’s used to pretty girls around the office now. In fact, I think it pleases her. It’s completely unfair to plain people, I know, and I’m certainly no paragon of beauty. But I like what it does for the office. It’s American to be beautiful. Does that make any sense? I think of America as strong bodies and straight legs and good teeth and suntans and quiet beauty. Not the Hollywood junk. So I feel more like a working American in an office which employs pretty girls as file clerks. My weakness,” Baxter said, smiling and shrugging. “Quiet beauty.”

Larry nodded and said nothing, but he thought of Maggie’s shrieking loveliness.

“About you,” Baxter said, spreading jam on one of the muffin halves. “What were your impressions of Hebbery?”

“He seemed like a nice person and a competent architect.”

“Are you reluctant to talk about him?”

Larry smiled. “To his employer? Yes.”

“He’s a good man within his own sphere,” Baxter said. “He’s in no danger of losing his job with us no matter what you say. Now, what did you think of him?”

“I imagine he was an honor student in a Connecticut high school,” Larry said. “He probably went on to Harvard, where he became a member of the chess team in his freshman year.” He thought for a moment. “He made Junior Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated cum laude.” Again he stopped, thinking, and then he nodded, his impression complete, and the words flowed from his mouth. “He doesn’t wear his Phi Bete key because he doesn’t like to show off, except at school functions where he feels it’s important. Actually, he always feels it’s important and will look back upon having made Phi Bete in his Junior year as one of the real achievements in his life. He copped a straight A average in every theory course he ever took, and excelled in draftsmanship. His planning problems were always turned in a week before the instructor’s deadline, spotlessly submitted, with no erasures. He should have gotten A’s but he didn’t because his spotless, exquisitely executed drawings somehow lacked imagination.”

“Go on,” Baxter said.

“He talks too much about how much he likes Puerto Rico. I think he really hates it. His wife certainly hates it. In early November, she was asking about Christmas in New York. But he filled me in beautifully on the problems I was to study, and he had the decency and good sense to know I’d work them out my own way in my own time. He was a cordial and gracious guide and host to us, but I wish his Spanish didn’t rely so heavily upon the single word bueno. That’s all I think about Frank Hebbery.”

Baxter nodded thoughtfully. Silently, he worded his next question, and then said, “What do you consider the architectural dangers of an unplanned but expanding community?”

“In brief? I’d say deterioration and obsolescence.”

“Have you ever done any city planning, Larry?”

“I began a job for a Long Island town but had to quit when they couldn’t appropriate the necessary funds.”

“Then you know what it entails?”

“Yes. I assume we’re discussing modern city planning and not the outmoded concept of the city beautiful?”

“That’s right.”

“Well, it’s a two-part project. The first part, and easily the most important, would be the study of sociological and economic data.”

“Such as what?”

“Population growth, industrial potential, natural resources, transportation facilities...”

Baxter nodded.

“And then, of course,” Larry said, “would come the actual physical planning of the environment.”

“By which you mean?”

“The physical structure. Details like how far a building will be set back from a road.”

“How long do you suppose it would take to work out a master plan for a place the size of Puerto Rico?”

“For the entire island, do you mean?”

“Yes.”

Larry was silently thoughtful. After a long while, he said, “Five years.”

“Oh, surely it could be done in much less time than that,” Baxter said.

“Not if it’s to be done well,” Larry answered. “Generic planning can’t be done overnight. An island-wide project would entail a study of each of your major cities with a view toward urban renewal or redevelopment. You’d have to plan new cities wherever the need is indicated, find ideal locations for residential growth and recreational spaces, industrial parks. You’d have to study your existing roads and then consult with highway engineers as part of the overall scheme of relating new transportation patterns with natural resources. And in addition to your master plan, you’d need a detailed study of at least one area. I don’t see how all that can be accomplished in less than five years.”

“Neither do I,” Baxter said promptly, and Larry realized he’d passed through a trap unharmed. “Do you think Hebbery is the man to handle such a development project?”

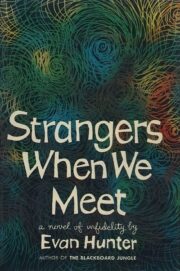

"Strangers When We Meet" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strangers When We Meet". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strangers When We Meet" друзьям в соцсетях.