“No,” Larry answered without hesitation. “Why?”

“Because Baxter and Baxter has been asked to do the job.”

“Planning the island?”

“Planning all of it,” Baxter said, his eyes glowing. “You know what Sert’s done on a limited scale in Cuba and South America. Well, we’ve got an entire island to change from dirt and filth and disorganized growth to beauty and cleanliness and directed expansion! My God, where’s the challenge of planning Great Neck when you compare it to this? Can you visualize that island fifty years from now? Can you visualize what five years of intense planning can do for it?”

“It can make it a dream island,” Larry said.

“A reality, Larry.” He paused. “Will you be my assistant?”

All he could register for a moment was complete shock. Speechless, he stared at Baxter.

“Not an errand boy and bottle washer,” Baxter said. “A real assistant to work with me on every phase of the study and plan. What do you say?”

“I haven’t caught my breath yet!”

“Then catch it. I’m going down in September to enlarge the field office. I’m taking some of the New York staff with me. I’d like you and your family to come along.”

Sudden doubt crossed Larry’s face.

“What’s the trouble?” Baxter asked.

“Nothing. I’m... I’m flattered and... and overwhelmed. I...”

“You shouldn’t be. I think you’re talented and imaginative and blessed with foresight. You should have won first prize in 1952, and I’m offering you first prize now. The opportunity to accept an architectural challenge of scope and magnitude. Or would you prefer the obscurity of residential design for the rest of your life?”

“No, but...” Larry paused. “I’ll have to think about it.”

Baxter looked at him curiously. “I didn’t imagine I’d meet with any difficulty,” he said. “I honestly thought you’d leap at the opportunity. Must I convince you?”

“It’s not that. I...”

“Larry, this will be just about the most highly publicized architectural venture of the century. Succeed with this, and your name goes into the architectural primers, I can guarantee that. And if you’re thinking in terms of money, the job is worth a small fortune to us. You’ll be paid regally.”

“But it would mean leaving New York for five years.”

“Certainly. But your wife and family would go with you.”

“Yes, but...”

“Five years is a short time to invest in a sure future, Larry.”

“I’ll have to think about it,” Larry said.

Baxter seemed more puzzled. He stared at Larry uncomprehendingly. “I want you along,” Baxter said. “If I can’t have you, I’ll handle it myself with whatever help my staff can give me. Do you know what I’m saying?”

“I’m not sure.”

“I’m saying that as far as I’m concerned, the job is open until the day I get on that plane in September.”

“I appreciate that,” Larry said.

“But I hope you’ll call me tomorrow to say you’re coming along.”

“I wish I could say it right now,” Larry said. “But I’ll have to think about it. September, you said?”

“September. Talk it over with Eve. Make sure it’s what you want.”

“It sounds like everything I ever wanted,” Larry said.

There was a curious sadness in his voice. For a moment he seemed terribly troubled and unsure, so much so that Baxter almost reached out to lay a reassuring hand on his shoulder.

“Think about it,” Baxter said gently. “Talk it over with Eve.”

He did not talk it over with Eve.

He did not even mention the proposal to her. He knew exactly what her reaction would be. Grab it, she would say. Take it, fly with it, soar with it! This was the golden chance, the dream offer, the jackpot tied with a bright silver ribbon!

He could visualize himself in Puerto Rico, a different Puerto Rico this time; not a tourist’s island, but a place to live and work.

In Puerto Rico, he was the handsome Americano. He was the respected architect who had come with a solution to the people’s problems. He was the hero who had come to liberate the land from filth. He would wear white ducks and he would get deeply tanned, and his eyes would be very dark, and there would be understanding intelligence in those dark eyes. They would have a house, he and Eve and the kids, and perhaps there would be a banana tree in the back yard, and wild orchids growing, and he could set up the drawing board there after a day of conferences and doodle with ideas as the afternoon lengthened into purple dusk.

He would come inside then, his white shirt open at the throat, the sleeves rolled up onto his forearms against his deep tan. He and Eve would sit on the screened terrace and sip their rum drinks or their gin drinks; there would be bird sounds in the garden and perhaps, in the distance, the steady thrum of guitars. They would have a quiet dinner served to them by native help, and then they might go for a walk under crisp Puerto Rican starlight, say hello to people in Spanish, or chat a bit about the rainy season.

Or perhaps they would drive out into the country and stop for roast pork, watching the pig turning on the spit, a glistening burnished brown, the fats dripping onto the charcoal fire, the fire spitting angrily as the meat rotated. They would eat their pork and drink wine, and when they went home they would make love. They would make love the way they used to. In Puerto Rico, everything would be all right between them again.

And during the day, there would be the challenge.

The study, the steady compilation of facts and figures, the tentative stabs at solving the problem, the firmer thrusts, the solidified ideas, the problem slowly succumbing to creative onslaught, and finally the plan. He could almost see the plan on paper. He could visualize the island years from now, when the plan had left paper and become reality. Fifty years, a hundred years, a thing of form and beauty on an azure sea. He could see himself walking through the streets and thinking, I helped create this.

The dream was within reach. All he had to do was grab it.

But there was Maggie.

He had told Altar that all he wanted was to be happy. He did not think he was lying to himself at the time. But now, with everything he desired being offered to him, he began to wonder seriously about his own goals.

Sitting behind his drawing board in the third bedroom of his development house in Pinecrest Manor, he asked himself, What the hell do I want out of life?

I want to be happy, of course, but that’s pure rubbish. Everyone wants to be happy. You can probably be happy dead as well as alive. Life is not a prerequisite for happiness. The dead sleep exceedingly well, with no problems whatever, and they are no doubt deliriously happy. But they are also dead, and I’m concerned with what I want out of life.

All right then, I want to be famous.

That’s reasonable, an attempt to dissect this thing called happiness. Everybody wants fame, or at least recognition. And, like all human beings, I want to feel I’m different, unique. I want identity. I want to know I’m unique and loved for my very uniqueness. I want to know that I’m a very complex, very individualized, very important person. I want to be me. This is my fame, and this is what I want. But I also want fortune.

I want to be rich.

Maybe everyone doesn’t want to be rich, but I do. I need money. I like money. It’s good. Not because it’s crisp and green, but only because it buys things. And buying things helps me to realize myself. A look down the price column of a menu destroys a little of my ego, and am I not a cipher, a less-than-cipher, a zero when I have lost that?

I want money, he thought, lots of it; and I want respect.

Respect as a man, as an architect, as a human being with dignity. And this too, like fame and fortune, isolates me as an individual. Being alive is simply being myself, and being myself is happiness.

I want Maggie, he thought.

I want her because when I’m with her I’m completely and indisputably me.

But how much do I want her? If I could have Maggie alone, would I be willing to ignore fame, fortune and respect — all of which are being offered to me — and be content with what she is and with what she brings to me? Am I willing to sacrifice one identity on the altar of a second identity? And which is the true image?

Are there two Larry Coles, and which one do I want to be? How can I possibly think of refusing Baxter’s proposal? Four months ago, five months ago, before I knew her, I would have accepted it instantly. And now a casual exercise — was it ever a casual exercise — has become an indestructible bond. I cannot leave her. I cannot go to Puerto Rico and be away from her for five years. I cannot.

I’ve found myself, he thought, but the person I found is lost.

19

Eve could not have asked for a more beautiful party night.

The temperature had hovered in the low forties all day long, dipping to thirty-three degrees along about seven o’clock when she and Larry were dressing the children for bed. It was bitingly cold outside, but stars had appeared in a cloudless black sky and a brilliant moon tinted the snow-banked streets and the plants and the houses with silver. The sharp tang of the cold was a thing to savor, but the warm glow of the houses beckoned one indoors again. It was a wonderful night for a party, and when Eve left Larry with the children to read them their story, she was humming contentedly.

He joined her ten minutes later as she was pulling on her nylons. Sitting on the edge of the bed, she looked over her shoulder when he came into the room.

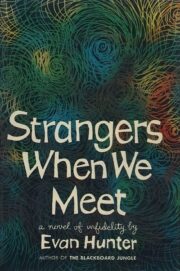

"Strangers When We Meet" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strangers When We Meet". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strangers When We Meet" друзьям в соцсетях.