Fran burst out laughing. Together, they went into the living room.

“The only way to beat crab grass,” Arthur Garandi was saying, “is to pull it out by the roots. That’s the only way.”

“There are some effective chemicals on the market,” Felix said.

“By the roots,” Arthur insisted. “It’s like cockroaches. The only way to kill them is to step on them. Well, it’s the same way with crab grass.”

“Stop talking about cockroaches,” Mary Garandi said. “Everybody’ll think we got them.”

“Who’s got cockroaches?” Max asked, coming from the bedroom with an imaginary spray gun and a hunter’s gleam in his eyes.

“Oh, my God, you see!” Mary said.

“You got cockroaches, little lady?” Max asked.

“No, no!”

“I’m Max Levy, Cockroach Killer. This is my assistant, Fran.”

“Hi,” Fran said.

“My wife Betty,” Felix said, handling the introductions. “Paul and Doris Ramsey. Arthur and Mary Garandi, and Mrs. Garandi.”

“You have two wives, Arthur?” Max asked.

“No, she’s my mother,” Arthur said.

“Your mother indeed! This young lady? Preposterous!”

“Him I like,” the Signora said.

“You I like,” Max said, bowing. “Let’s get crocked together.”

“Together or alone,” the Signora said, “that is the general idea.”

“You’re Italian,” Max said.

“With a name like Garandi, how did you guess?”

“It’s not the name. I like Italians. I was in Italy during the war. They called me The Flying Jew.”

“Who did?”

“The Italians.”

“Why?”

“Because I was a flying Jew,” Max said, shrugging.

The doorbell rang, and Eve went to answer it.

“Excuse me, plizz,” Murray Porter said in a thick feigned dialect. “This is maybe Temple Emmanuel?”

The Porters had arrived. The party was ready to start.

The more they drank, it seemed to Larry, the more obnoxious they got. And the more obnoxious they got, the more they drank. And to blot them out, he drank with them.

He had lost count of how many drinks he’d had. There was music coming from the living room, but no one was dancing. In Pinecrest Manor no one danced at house parties; dancing was reserved for the yearly beer parties. There was the sound of loud laughter, oh how these sturdy goddamn rafters rang with laughter, and the sound of loud conversation, and a feeling of too many people in too small a house. He stood alone by the kitchen sink, holding a glass, and he thought, This is a rotten party. Maggie, this is a rotten party, and I should have let you come.

When the Signora walked into the kitchen, he looked up but he did not say hello. She studied him for a moment.

“Any more Scotch?” she asked.

“Sure,” Larry said. He picked up the bottle, held it up to the light, took her glass, and poured. “Water, soda? I forget.”

“Soda.”

He poured from the open bottle on the sink, and then handed her the glass. “Lousy party, ain’t it?” he said.

“It’s a good party.”

“If I wasn’t the host, I’d leave,” Larry said. “I may leave anyway.”

“Where would you go?” the Signora asked.

“There’s lots of places to go, Signora,” he told her. “Lots of places.”

“To a lecture?” she asked.

He looked up suddenly. As drunk as he was, his eyes narrowed and he studied her suspiciously. “Why would I want to go to a lecture?”

“You like lectures, don’t you?”

“Sure, I do.”

“I do, too. Maybe I’ll go with you some night.”

“They’re very technical,” Larry said. “Even Eve doesn’t come.”

“Of course,” the Signora said. “Besides, I’m very rarely free. I’ve been baby sitting. It passes the time, I get paid for it, and it’s right in the neighborhood.”

“That’s good, Signora. That’s very good.”

“I baby sit for Margaret Gault quite often,” the Signora said.

Larry looked up. Mrs. Garandi was studying him with expressionless brown eyes. He looked at the white-haired woman, the patrician face set incongruously upon the thick body. The eyes were blank, but the mouth was sad.

“She goes out a lot,” the Signora said, “and I sit for her.”

“That’s nice,” Larry said carefully.

“Do you think she goes to... lectures?”

“I don’t know where she goes,” Larry said, “and I don’t much care.” In his drunkenness, he wondered why Maggie had never mentioned that the Signora sat for her. Couldn’t she see the danger in that? Didn’t she realize the old lady lived right across the street, could observe his comings and goings and relate them to Maggie’s?

“She’s a beautiful woman,” the Signora said.

“Beauty’s only skin deep. You don’t have to be happy just ’cause you’ve got beauty. Didn’t you know that?”

“Is she happy?”

“How do I know?”

“Are you happy?”

“I’m very happy. Whisky makes the whole world happy. Have another drink, Signora.”

“Why don’t you get out, Larry?”

“Out where?”

“Out of Pinecrest Manor. This isn’t the place for you. This is no good for you.”

“I like it here.”

“Do you love Eve?”

“Sure, I love Eve.”

“Then get out.”

“I can’t go anyplace else.”

“Why not?”

“I can’t, that’s all.”

“Why not?”

“Signora,” Larry said drunkenly, “life is a pretty complicated thing, you know? It doesn’t work the way you figured it was gonna. It just goes along its own merry goddamn way and you call the plays as they come. That’s what, Signora.”

“Get out of Pinecrest Manor. Go someplace else.”

“Is it gonna be any different anyplace else?” Larry asked. “Where’s the pot of gold, Signora? Where the hell is the pot of gold? I can’t even find the goddamn rainbow!”

“Margaret Gault isn’t the pot of gold,” the Signora said, and he looked at her long and hard, and neither spoke for a long time.

Then he said, “Signora, I like you a hell of a lot. You’ve got it all over that creepy son of yours and his Minnie Mouse wife. Only one thing, Signora. Mind your own business.”

“I like you, Larry,” she said. “I always have. I’m trying to help you.”

“There isn’t nobody who’s going to help me but me myself,” he said.

“How?”

“I’ll figure it out. I’ll cross the bridges when I come to them. If there’s no bridges, I’ll design some. I’m an architect, ain’t I? Am I not?”

“You are.”

“Sure, I am. A big architect! You can tell just by looking at my house, can’t you? My magnificent palace! But then this is everybody’s palace, ain’t it, Signora? This nice lovely Pinecrest Manor with the fresh air for the kids and the patios where you drink gin and talk about lawns and clean living? The dream palace with the spotless lawn, no crab grass, Signora, it is absolutely essential that there be no crab grass. You know something?”

“What?”

“Who cares about crab grass?”

The Signora smiled.

“Who gives a damn if crab grass devours the whole lawn or the entire development or even the world? I don’t give a damn about it, and I don’t think anybody else really does either. But they’ve learned that their sixty-by-a-hundred coffin has to be a green coffin. If it isn’t, some son of a bitch up the street will report you to the Civic Association for spoiling the looks of the goddamn cemetery, pardon the language.”

“Larry, if you...”

“They don’t care, Signora. Here they are in the country, why should they care? Here’s the big dream. The corner plot, and the white house with the pink shutters, and the entrance hall, and that washing machine humming in the basement, and that one-year’s free service contract for that oil burner humming in the basement, and that slate patio in the back yard, and that new garage going up with its Building Permit tacked to the door. Here’s the big dream, who cares if we ate beans and bread crusts for the first fifteen years of our married lives?

“Signora, here are all these people in the idyllic little collections of crackerboxes with the pastoral-sounding names dreamed up by copywriters in Madison Avenue offices who live in the heart of the big, dirty, no-fresh-air city. Maplebrook Acres! Or Hillside Knolls! Or Four River Birches! Here they are ready to start living that big fat American dream! But when the hell does the living start?

“When is there time, after that crab grass has been picked, and that storm replaced by a screen, and that Boxer walked, and that newest shrub planted, and the fence put up, and the gable painted, and the patio built, and the lawn mowed and fertilized and limed and edged, and the slide-upon and the swing erected, and the rubber swimming pool inflated and filled, and the automatic sprinkler set on the lawn, and the forsythia cut back, and the asphalt tile put into the basement — when is there time to sit on that new patio and have that lousy gin-tonic you’re thirsting for? When is there time to live?”

“There’s time to live, Larry,” the Signora said.

“Oh, sure, there’s time. We have fun at our gleeful out-door barbecues, don’t we, where the flying sparks almost burn down the whole damn development, and where every scroungy hound in the neighborhood comes around to snatch some beef, and where the hamburgers are burned and where your identical neighbor who is just as old as you are and who has just as many kids as you have and who earns as much money as you do and who is at that very moment in his identical back yard having the same identical barbecue yells over, ‘Hi, there, neighbor! Having a little outdoor barbecue?’

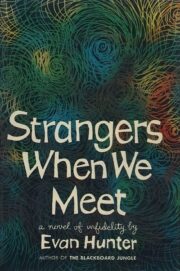

"Strangers When We Meet" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strangers When We Meet". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strangers When We Meet" друзьям в соцсетях.