The leaves had been wet that day, despite the heat of the sun. It was impossible to move through the jungle without getting soaked to the skin. It was hard to breathe in the jungle. The air was dense and still, crowded with the exhalation of growing things, crowded in a tight, hot, timeless green prison. He moved through the jungle alone. He knew the rest of the men in his company were spread out in a wide arc working its way across the face of the island in a mopping-up operation. But if a man moved five feet away from you into the foliage, you could no longer see him. And so, though he knew he was part of a team, he felt alone.

He did not want to use his machete. If he ran across any Japs, he wanted his rifle in his hands where he could fire it instantly. He did not want to be caught swinging a machete by any goddamned Gook. He wanted to be ready. And so he moved cautiously, the machete speared through his belt to the right of the grenades. He wore no pack. He wore jungle issue gear and a netted helmet, and the sweat ran down the sides of his square face, trickled from his strong jaw onto his neck. The stock and barrel of the Browning automatic were moist with jungle sweat. He kept his finger inside the trigger guard, ready to fire. He did not want to be ambushed.

When he came upon the Jap, he was quite surprised.

He would have fired instantly if the Jap had burst from the jungle swinging a sword or leveling a rifle. But he had stumbled upon the enemy completely unaware; perhaps he should have fired the moment he saw him anyway, but he did not.

The Jap was an officer.

He knew that the moment he saw the Samurai sword in his belt and the insignia of his rank on the lapels of his blouse. He could not read the rank, but he knew that no enlisted Japanese soldier wore such insignia. The man was sitting against the trunk of a tree smoking. He carried no rifle. There was a pistol hanging in a holster on his belt. That, and the long Samurai sword. Nothing else.

He had not heard Don. He sat smoking leisurely under the tree, as if the island had not been exposed to bombing and shelling for the past four days, as if a Marine assault wave had not stormed the underwater barbed wire and the concrete pillboxes on the slopes facing the sea, as if the Army had not swarmed ashore and driven the enemy back across the island, as if the simplest mopping-up exercise were not now in operation.

He sat smoking casually. He might have been sitting on an outdoor terrace somewhere in Fukuoko, listening to a woman play a Japanese stringed instrument, watching the sun sink, watching the mountains of his homeland turn purple with dusk. He seemed completely unconcerned with the war, with the island, with the uniform he was wearing. For an instant suspended in time, Don had the strangest urge to walk to the man, sit down beside him, and share a smoke with him. And then the absurdity of the whim struck him. He felt the hackles at the back of his neck rising, felt his scalp begin to prickle beneath the netted helmet.

The Japanese officer looked up.

His eyes locked with Don’s. He made no move for either the pistol or the sword. He sat beneath the tree with the thin cigarette curling smoke up past his face. The face was bearded and browned. The cheekbones were high, and the nose was flat, the eyebrows thick and black over hooded Oriental eyes. The man smiled. A gold tooth flashed in the corner of his mouth.

“Ah,” he said in English. “At last.”

His use of English startled Don. He knew the man was an officer, but he had not expected him to use English, and his knowledge of the language made him seem less the enemy.

“Don’t move,” Don said.

The man was still smiling. “I won’t,” he answered. “I’ve been waiting for you.” His English was very good. He had probably been educated in the States, Don thought, and this too lessened the concept of enemy.

“Get up,” Don said.

The officer rose. He was very small. He didn’t seem more than a boy. It was difficult to judge his age. Don knew an officer couldn’t be too young, but the man nonetheless had the stature of a boy, and would have seemed adolescent were it not for the thick black beard and the Oriental eyes — somehow aged, somehow ancient.

“Drop your belt,” Don said. “Quick.”

The officer continued smiling. He unclasped his belt. The holster, pistol, sword and scabbard fell soundlessly to the jungle floor, cushioned by the lush green mat.

“And now?” the officer asked.

“Hands up,” Don said, and immediately wondered if he’d made a mistake, wondered if the Jap were holding primed grenades under his arms, tucked pinless into his armpits.

“You’re not going to take a prisoner, are you?”

“Hands up!” Don shouted, still worried about the grenades, but more afraid that the Jap would leap at him. He was sweating heavily now. The sweat was cold. He could feel his fingers trembling inside the trigger guard of the piece.

The officer raised his hands. “Didn’t they tell you about taking prisoners?” he asked.

“Shut up,” Don said.

The man continued smiling. “I was waiting for you,” he said, “because I want to die.”

“You shut up,” Don said. “Come on, we gotta... we gotta move back.”

“I want you to shoot me,” the officer said.

“Never mind what you want. Come on.” He jerked up the BAR. “Come on.”

“No,” the officer answered, still smiling.

They were separated by five feet of jungle vegetation. They stood opposite each other, and Don swallowed the tight dryness in his throat, and then the bird began shrieking somewhere in the trees, a crazy discordant shriek, CAW-CAW-EEEEEE! EEEEE-CAW! EEEEE-CAW! The jungle reverberated with the terrible music of the bird.

“Come on,” Don said.

“Shoot me,” the officer said, smiling.

“I ain’t gonna—”

“Shoot me, you Yank bastard,” the Jap said.

“Look. Look, I gotta take you back to—”

“Shoot me, Yank warmongering bastard. Shoot me!”

The bird continued to shriek. EEE-CAW! EEE-CAW! Except for the bird, the jungle was still. The officer continued smiling. He continued watching Don and talking to him, and smiling while the bird shrieked and shrieked. The BAR was getting heavy. Don’s hand was wet on the barrel.

“Come, Yankee son of a bitch, shoot me. Shoot me, you dirty Yank bastard!”

Don swallowed again. He could feel the cords on his neck standing out, could feel his heart drumming in his chest. He was drenched now, soaked, standing with a lethal BAR in his hands, listening to the insane scream of the bird, listening to the rising voice of the officer, the smiling officer who calmly stood waiting to be killed. The string of epithets flowed from the officer’s mouth in rising fury, endlessly spewing. All the while, he smiled. All the while, the bird screamed.

Don did not want to squeeze the trigger.

He did not want to kill this man who had sat complacently and smoked his cigarette, who was a real man with a real face, a man with a boy-body and ancient eyes, who spoke English, who did not at all seem like a murderous enemy, he did not want to kill this man, he did not want to kill.

But the officer continued to hurl blasphemy at Don, smiling all the while, eventually striking a combination of words, whichever combination it was, a combination hurled from his smiling mouth unwittingly as he sought profanity after profanity, a combination which did the trick.

“Shoot, Yank bastard. Shoot son of a bitch. Shoot bastard. Shoot rotten rich American warmonger. Shoot big-shot Yank prick bastard. Shoot Yank jerkoff! Shoot rotten bastard mother-raper Yank! Shoot—”

He fired.

His finger jerked spasmodically on the trigger and then held it captured, and the automatic weapon bucked in his hands, and he could see the slugs as they ripped into the Jap’s tunic, tore into the Jap’s face, exploded the ancient eyes in pain. The officer fell to the jungle mat silently. The bird shrieked EEEE-CAW! CAW-CAW-EEEEEEE! and then was silent. Don began crying.

Sobbing, the tears streaming down his face and mingling with the sweat, he stood with the rifle dangling foolishly, and he said, “You shouldn’t have said that, you shouldn’t have said that,” crying fitfully all the while.

Now a decade and more later, in the back yard of a development house in Pinecrest Manor, he dropped his spade because he could no longer hold it in his trembling fingers.

“Margaret!” he shouted. “Margaret, where the hell are you?”

Angrily, he strode to the house.

23

They were almost discovered on a Tuesday in April.

“Overconfidence is the biggest danger,” Felix Anders had said as far back as February, but Larry had not paid much attention to him at the time. They were, after all, exceptionally careful; they no longer met and talked at the bus stop; they continually changed the place of their weekly assignation; they tried to alternate between day and night meetings; Maggie no longer used the Signora as a sitter; and Larry no longer used Felix Anders as a confidant. They had become expert at the dangerous game they played and, as experts, perhaps they became overconfident without realizing it.

Their overconfidence on that late Tuesday afternoon took them to a diner not a mile from Pinecrest Manor. It was, in all fairness, a place not frequented too often by residents of the development. There were closer and better diners. But it was only a mile away and they should not have stopped there for coffee on the way back from the motel.

They left the diner at about four-thirty. It was a bright sunlit day, and they walked hand in hand toward the Dodge. The car was parked at one end of the lot, alongside a high curbing. As they approached the car, they noticed that a dual-control automobile from a driving school was attempting to park behind it.

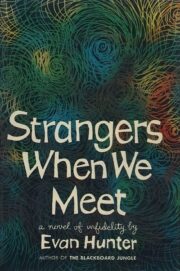

"Strangers When We Meet" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Strangers When We Meet". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Strangers When We Meet" друзьям в соцсетях.