“Was I?”

“Yes, you said he went in nineteen ninety-eight? Did he go in the spring or summer?”

“Why do you want to know?”

Ariel wasn’t about to answer that question, at least not truthfully. “I just can’t quite get it in my head. You see, I’m writing a social studies report.” That was true. “About our family.” Also true. “About cool things our family does.” Sort of true. “And Uncle Anthony is the King of Cool Stuff.”

Nana smiled, but it was a sad smile. “Yes, he is. Always has been.” She sat back and looked out into the garden. “You should have seen him as a little boy. The most beautiful child anyone had ever seen. Everyone said so. I couldn’t go anywhere without people stopping me—on the street, mind you—and commenting on what a beautiful child he was.”

Ariel refrained from asking where Dad had been in all this walking-the-beautiful-baby-around business. She wanted answers and while she didn’t completely have her head wrapped around the thoughts bubbling to the surface, she figured it was better to avoid bringing her dad into it.

“When he was young,” Helen continued, “Anthony went on any adventure his father and I allowed. When he was six, he asked to go to sleepaway camp in Vermont. Sleepaway camp at six!” Helen chuckled. “At ten, it was camp in Colorado. Then Montana. I couldn’t believe it. At seventeen, he wanted to travel to Costa Rica on summer break to build houses for the less fortunate.”

In some recess of her mind, Ariel remembered another conversation she’d overheard. Her dad and uncle going at it, yet again.

You had to go everywhere I did, her dad had shouted.

I looked up to my older brother. What of it?

You didn’t go because you admired me. You went to show that everyone, everywhere, loved you better.

Ariel had expected her uncle to deny it.

And they did, didn’t they?

Silence, followed by her dad’s cold voice.

Yes. They always loved you more.

Ariel hadn’t understood at the time, and she hadn’t thought of it again until now. Sitting with her grandmother, a sick feeling started to build in her stomach.

“Yeah,” she said with a laugh she didn’t feel. “Uncle Anthony is amazing. Costa Rica at seventeen. And you said he went to Africa in nineteen ninety-eight?”

“Yes. May nineteen ninety-eight. He hasn’t lived in New York full-time since.”

Ariel’s heart pounded so hard that she bumped the teacup, the china clattering. Helen jerked her gaze away from the window, her normal smooth beauty pinched as she took in Ariel. “It’s your father’s fault that he left, you know,” Helen said, as if trying to gain supporters to her cause.

“What do you mean?”

“It’s a very sad thing when one brother is jealous of another,” Nana said, her mouth sort of pinching together. “I’ll tell you for your own good, since you have a sibling as well. And so you can understand that your father is just plain being unfair to your uncle. Your father has always hated the attention Anthony received. So when Anthony wanted to go to camp, Gabriel made us send him, too. Vermont. Colorado. Costa Rica.”

Ariel wasn’t quite sure how to respond to this. I believe it was the other way around didn’t seem to be what Helen had in mind.

“And then Anthony met Victoria.” The pinched look turned bitter. “Even more than your father, Victoria was responsible for everything falling apart. As much as I’m not one to speak ill of the dead, the first time I met her, she looked like—” She cut herself off and focused on Ariel, her lips pursed hard. “Like a girl raised in a housing project. But your mother was smart. The next time I saw her, she was wearing a sweater set and pearls. She played Gabriel against my Anthony. In the end, she ran Anthony off to Africa, heartbroken, when she chose Gabriel over him. I’ve always wondered what Gabriel did to win her. He’d never won against Anthony. Ever.”

By then, her grandmother was leaning forward, intent, lost to her own words. Then she sat back abruptly and eyed Ariel warily.

Ariel sat, stunned. She couldn’t believe what her grandmother was saying. Uncle Anthony had said he met her mom first—but he’d dated her? More than that, how could Nana say this stuff about her dad?

She sat up straight. “A mom shouldn’t love one kid more than the other.”

Helen glanced out the window. “Mother or not, there are some people who simply pull everyone to them. Anthony is like that.” She looked back, directly at Ariel. “Your father always made it hard to love him.”

Ariel’s chest was burning so much that she couldn’t even think of what to say. So she jerked up from her seat and dashed to the front door, slamming out into the street. As soon as she managed to free her bike she pedaled as fast as she could back across the park to the Upper West Side, tears flying in the wind along with the streamers.

Twenty-three

PORTIA LOVED THE SMELLS of cooking and baking. It turned a house into a home.

It was October, barely two weeks after she and her sisters had opened up the test version of The Glass Kitchen. Standing at the sink, she washed her hands, getting ready to start cooking for the day. Ariel had been quiet lately, sitting at the end of the counter, busy doing homework and writing in her journal. But sometimes she just sat there, lost in thought, her brow creased. Portia had asked if anything was wrong. Ariel had blinked, then scoffed, diving back into homework.

And then last night Portia had dreamed of apples again. When her mind swirled with images of her grandmother’s moist apple cake, she had gasped awake, her heart pounding. Between Ariel, Gabriel, and her rapidly dwindling money, Portia felt as if a noose were gradually slipping tighter around her neck. And with every day that had passed, the knowing grew a little bit more. Part of her reveled in it. But the other part still held out against it, worried about what it meant to give in to the knowing completely.

Given the dream, she shouldn’t have been surprised a few hours later, as she stood at the counter making a fresh batch of sweet tea, when Cordelia arrived.

She looked tired and disheveled, distracted as she walked in carrying a bag of groceries. “I thought we could give that cake a second try.”

“What cake?” Portia asked carefully.

“The apple cake.”

The only thing that surprised Portia was the pure, unadulterated spark of excitement that flared inside her, as if finally she could let go of any remnants of worry.

Cordelia looked at her, though her eyes were dull. “I knew it. I knew that today was apple cake day. Just like I know that my life is over.”

Portia stiffened. “What?”

Olivia walked in next. “What do you mean your life is over? What’s wrong now?”

Cordelia looked her sisters in the eye, seeming to come to a decision. “You mean what’s wrong besides lying to people and telling them that Portia works with Gabriel Kane in order to get meetings?”

Portia’s head snapped back. “You really did it?” She had hoped there would be some explanation, some misunderstanding.

Cordelia pressed her eyes closed, then sighed. “Yes, I did it. I started out doing it the right way when I first tried to get appointments with investors. But I never got past the receptionists. Then I sort of casually mentioned that you knew Gabriel Kane, which morphed into you worked for Gabriel Kane, which morphed even more into you worked with Gabriel Kane.” She cringed. “That had people lining up to take a meeting with you.” Her face was red with strained emotion. “I shouldn’t have done it, I know. But with all this mess with James, I felt desperate. It was like getting the appointments was proof that I could make something happen in my life.”

Portia came over and took the bag away, setting it down. Olivia joined them.

“Hey, sweetie,” Olivia said, wrapping her arms around Cordelia. “It’s okay. It will all work out. Things always do. Just like it will all work out with James.”

“But it won’t. It turns out there’s an e-mail trail a mile long.”

Olivia couldn’t seem to help herself when she snorted. “Who, in this day and age, leaves an e-mail trail?”

“Obviously my husband.” Cordelia drew a shaky breath, and when she spoke, her voice cracked. “Me. Dirt poor. Again.”

Portia took her sister by the shoulders. “Not a single one of us wants to go back to our trailer-park roots. But whatever happens, I know you’ll get through this. Daddy taught us to be fighters. And I just realized that not one of us has been fighting for ourselves. Not really. Not well enough. We’ve been hanging in the wind, at the mercy of what comes our way. Daddy would hate that.”

She saw the shift in Cordelia’s eyes; she even saw it come into Olivia’s eyes, as if the mention of their father brought his strength into the room.

“You’ve been dealt a bad hand, Cord,” Portia continued. “But it’s time you started taking control in the right way. You’ve got to pull your head out of the sand, start fixing your life.”

Cordelia pressed her eyes closed. “But how?”

“I don’t know,” Portia said honestly. “But we’ll figure something out, just like we figured out how to open a version of The Glass Kitchen without money, and it’s working.”

She prayed she wasn’t lying.

“Now,” she said, stepping away with a decisive nod, “we are going to drink to that.” She retrieved three glasses and poured lemonade into each.

Portia and her sisters raised their glasses. “To Earl Cuthcart,” she said.

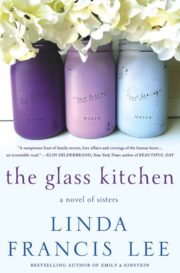

"The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters" друзьям в соцсетях.