She groaned, then slid down even farther front of the TV. Obviously, she should feel guilty about camping out on Marcus and Stanley’s overstuffed chair, not facing her problems head-on—especially after that whole don’t be a chicken speech she had given Cordelia. She was starting to feel guilty. But just a little.

“I’m fine,” she said.

She heard Stanley shuffle in; the two men whispered for several moments. Portia heard phrases like: Not natural for a woman to let herself go, Too much TV isn’t good for her psyche, and, Ain’t Misbehavin, really was one of the most overrated musicals of the 70s.

“I can hear you two.”

“We just think you’re a bit, well, discombobulated.” This from Marcus.

“Pshaw. She’s a wreck. And she looks like one, too.” Stanley.

Portia jerked up. “Fine. I’ll go take a bath, wash my hair.”

“Sweetie,” Marcus said, his grimace apologetic. “We weren’t talking about your hair, which, by the bye, is hideous. But we aren’t ones to judge.”

Portia scowled.

“We’re referring to your mental state. You are a wreck. We discussed it after breakfast and decided we had no choice but to take matters into our own hands.”

Portia narrowed her eyes. “What did you do?”

The door buzzer sounded.

“Seriously, what have you done?”

“It’s for your own good,” Marcus said.

Stanley scoffed as he shuffled to the door. Next thing she knew, they had guests.

Portia jumped to her feet. “Traitor!” Portia glared at Marcus and Stanley. “You know I’m not in the mood for family!”

Marcus grimaced. Stanley shuffled back to his seat by the window, not one bit apologetic.

“You are the traitor!” Cordelia shouted. “Not taking our calls. Going MIA without a single word to let us know you were okay and not dead in a ditch.”

“I don’t do worry!” Olivia stated.

“Good God, look at you,” Cordelia went on. “You do look like you’ve been in a ditch.”

Stanley snorted in agreement.

“You need to stop with this nonsense.” Cordelia walked over to Portia, took her hand, and pulled her toward the staircase. “It’s time you rejoin the living.” She glanced over at Marcus. “I take it there’s a bathroom upstairs with a sink, running water?”

“Up the stairs, second door on the right,” Marcus supplied. “Her meager stash of belongings is in the bedroom one door beyond that.”

Portia didn’t know if she wanted to scream or cry as Cordelia and Olivia herded her up the stairs.

“I don’t need the two of you marching in here thinking you can boss me around!”

“We aren’t bossing you around,” Olivia said. “We’re taking charge while you’re mentally incapacitated.”

“I’m tired of this!” Portia snapped. “I’m tired of both of you always in my business. I’m tired of trying to live the kind of life I want, only to get upended every time I turn around!” Lord, it felt good to let it out. “And I’m tried of always having to save—”

She cut herself off. It only felt good for so long. She was angry at her sisters. But, really, she knew she was angry at the world. She had never been one to intentionally hurt anyone.

“Tired of having to save us,” Cordelia supplied for her.

“Of course that’s what she thinks,” Olivia said to Cordelia. “Poor little Portia is sure she wouldn’t be in this mess if the two of us hadn’t browbeaten her into this whole Glass Kitchen fiasco. And if she hadn’t been busy trying to get the café started, then she would’ve been able to find a real job and not have to take one cooking for Gabriel, which is the only reason she got involved with him and HAD SEX!”

“Olivia!” Portia snapped.

“Of course she knew,” Cordelia said. “She’s Olivia. And of course she told me.”

“It sucks being you,” Olivia added with more than a little sarcasm.

Portia ground her teeth as her sisters pushed and prodded her down the hallway of Stanley and Marcus’s old town house. “You don’t know the first thing about what it’s like to be me.”

Olivia held up her hand, seesawing her thumb and forefinger, much as she used to do when they were children. “The world’s smallest violin is playing for you, baby sister.”

Cordelia rolled her eyes. “The fact is, Portia Desdemona, you have a gift or talent or maybe even a curse, which is really nothing more than a wildly in-tune intuition that freaks you out. For that matter, it freaks me out. But so what?”

Olivia nodded like a member of the choir. “So what!” she echoed.

Portia’s frustration bubbled up. “You don’t understand!”

“Stop feeling sorry for yourself!” Cordelia barked. “Did it ever occur to you that I would love to have a gift? Any gift? That I’d give my eyeteeth to feel special, to feel like I’m someone other than a woman who just tries to get by in a regular life in a regular world that falls apart for no good reason?”

Olivia and Portia stopped and gaped at Cordelia.

“Who knew?” Olivia said. “At least about feeling regular. How come you forgot to act regular, if you’re feeling that way?”

Tears suddenly welled up in Cordelia’s eyes.

“Olivia!” Portia snapped, and turned to her older sister. “Cordelia, honey, your world isn’t falling apart. James is going to be fine. You all are going to be fine.”

Yet again, it was always this way with them. Sniping, fighting, arguing, taking sides as alliances ebbed and flowed through each encounter. Now the sisters stopped and stared at one another, then did what they always did best: They sighed—half a laugh, half resignation—then hugged.

“We don’t care what you do, Portia,” Cordelia said, choked up. “Just do something. Stop hiding. You can’t keep living a half life, not embracing the knowing, but not embracing anything else, either. You’ve got to find a way to live your life, sweetie. Not Gram’s, not Robert’s, not ours. Yours. And that takes being strong enough to stand up to whoever is trying to sway you. Even if it’s us.” Cordelia gave Portia a little shake. “Now, clean up. Olivia and I are here to help. But you have to let us know what you want help with.”

The sisters left Portia standing in the bathroom. She looked in the mirror, giving herself a hard glare. “You are not this person,” she said to her reflection.

Thirty minutes later, Portia was bathed, dressed, and sitting cross-legged on the floor in her borrowed bedroom. Cordelia and Olivia had left, but not before she promised to call them tomorrow with a plan.

Portia took a deep breath, unzipped her suitcase. She sat there for long minutes more, then nodded her head and pulled out all three Glass Kitchen cookbooks. Whether she liked it or not, the knowing was her legacy. It had led her in so many ways, giving her answers, even if she didn’t like the answers it had given. But she couldn’t deny that the answers were true.

She didn’t bother with the first two books. She went straight to the third volume. The one Gram had always said wasn’t for novices. The one she hadn’t read until now.

She cracked the old spine and found spidery handwriting on the first page.

Every kitchen should be filled with glass—to drink from, to see through, to reflect the light of a wonderful meal prepared with love. To ensure that the light is not lost, I have filled these pages with everything that has been passed down to me from earlier generations of Cuthcart women. I hope each generation to come will do the same.

Imogen Cuthcart

The Republic of Texas, 1839

Portia started to read the fragile pages, first tentatively, then greedily. Images swirled as she read. Stews and roasts, herbs and spices, broth and gravy, cookies and pies. Sweet and sour. Joy and laughter, pain and sorrow. No life could be without these.

The language was stilted, the meals old-fashioned, but the advice was progressive, considering how old the book must have been. Each time Portia came to a notation, she recognized the ones that her grandmother had made, modern takes on antiquated forms of cooking, be it the update of a gas oven from coal-stoked, or a mixer to replace beating a cake by hand.

There were as many recipes for folk medicine as for meals. Obviously food had been the main source of healing for her forebearers. Gram had traded in her own version of food as a great healer, both physically and mentally. What surprised Portia was how each of these older, more complicated entries made so much sense to her, as if she already knew the wisdom she found copied down so carefully over the years, as if she had been born with a knowing that was far deeper than her ancestors’, truly deeper than her grandmother’s, as Gram had said.

Portia turned the last page and the breath rushed out of her. Gram had written this page herself, years after the book was originally compiled.

I dreamed a meal. A big meal. A final meal. I keep telling myself that it’s impossible to know for sure. My knowing is coming in fits and starts these days. But the images of food in this meal are strong, and I’ve been at this long enough to know, to feel certain, that when I see this meal, it will be time for me to stop. What I don’t know is what I will do when my turn is over, when it is time for me to pass the baton. How will I be able to bear it when my whole life has been the knowing?

Though that shouldn’t be my worry. I should worry that I haven’t taught Portia what she needs to know. Why is it so hard for me to let go? Why is it so hard for me to teach her? Why won’t I let her read any of these books, and most especially this one?

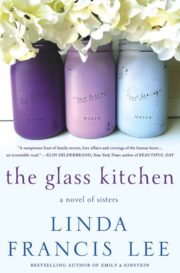

"The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Glass Kitchen: A Novel of Sisters" друзьям в соцсетях.