Ben must have felt sentimental about her to have had the spinet removed to Australia.

One day he said: “You’d miss me if I went away, Jessie.”

“Please don’t talk of it,” I begged.

“But I want to talk about it. I've got something very important to say about it. You don’t think I’d go away and leave you here, do you ? If I went I’d want you to come with me.”

“Ben!”

“Well, that’s what I thought. We’d go off together. How’s that?”

I immediately thought of myself going into the drawing-room at the Dower House and announcing my departure. They’d never let me go,” I said.

“Oh yes, they would… when I got at them.”

“I don’t think you know them very well.”

“Don’t I just! They hate me, don’t they? I took their fine mansion away from them. For hundreds of years there had been Claverings at Oakland and then along comes Ben Henniker - an old gouger - and swipes the lot. Well, of course, they hate me. There’s a bit more to it than that, though. I met your grandfather before I came here. I’ve got to tell you. I don’t want any secrets between us … well, not more than we can help. Your family’s got a special reason for hating me.”

“Please tell me,” I begged.

“I told you some of it. There’s truth and there’s half truth, and it’s funny what picture you can build up by telling just what you want to tell and holding back the rest. You can make a fine picture of it and it all looks so natural … but then out comes the truth and that puts a very different complexion on it. I told you I came down here and saw the house and made up my mind I was going to have it, and I told you I made a fortune and put myself in a position to buy it. All true. Well, there was I with my fortune and there was Grandfather Clavering finding it hard to make ends meet but stumbling along somehow like his ancestors had before him. I’m a wicked old man, Jessie. That’s what you’ve got to learn. I’m rich. I’ve got money to play with. The world’s my stage and I like to shift the players around a bit to make them dance to my tune. I’m also a bit of a gambler, as I’ve told you before. Not so much as the Claverings, though. I wonder if you’re a gambler, Jessie. I reckon you are. You’re a Clavering, you know.

“Your grandfather belonged to one of those London clubs. I knew it well , .. from the outside. I used to pass it with my tray of ginger breads when I was first starting out. Fine, imposing sort of place with some lions guarding the door to keep out poor gingerbread-sellers like me. One of these days, I promised myself, I’ll strut up those steps with the best of ‘em, and one day I did. I joined this club and there I met your grandfather. We discovered a love of a game called poker. It’s one where you can lose a fortune in an afternoon and I saw that he did. Well, it took two or three afternoons actually. I made up my mind I was going to sit at that table till the day came when he’d have to give up Oakland. It was easier than I thought.”

“You … deliberately did that!”

‘now don’t look at me like that, Jessie. It was all fair and above board. He had as much chance of winning as I had. I wasn’t staking all I’d got, though. He was the more ruthless. Gamblers both-I was staking a fortune; he was staking his house, and he lost. He had to sell, and I got Oakland Hall. They never forgave me for that . particularly your grand mother. It was no use trying to be neighbourly after that.

Now I’ve told you. ”

” Ben,” I said earnestly, ‘you didn’t cheat? That’s what I want to know. I couldn’t bear it if you had.”

He looked straight at me.

“Cross my heart … as we used to say when I was a little ‘un.” He put his forefinger to his lips and chanted :

“See my finger’s wet. See my finger’s dry (he wiped it on his coat) Cross my heart (waving his hand across his chest) And never tell a lie.”

He grinned at me.

“No. It was a gamble … nothing more. I just won.”

“And my grandmother knew this?”

“Yes, she knew, and she’s hated me ever since. Not that I care for that, but I shouldn’t like it if you took against me because of it.”

“No, I don’t, Ben. It was a fair game and he lost.”

“Goodo. Now we understand each other. I reckon I could arrange for you to come to Australia with me.”

“It sounds so exciting I can’t believe it.”

“Well, we’ll start hatching plots, shall we?”

They’d be horrified, I know. “

That makes it all the more exciting, doesn’t it? ” he retorted mischievously.

He would sit there laughing to himself and I wondered what was in his mind. He talked a great deal about the Company, the town which had grown up and was known by the name of-the Fancy or Fancy Town. He often mentioned Joss; in fact he seemed to be obsessed by Joss, which I supposed was natural since he was his son, but the more I heard of that arrogant gentleman the less I was able to share Ben’s enthusiasm for him.

It was always: “When you’re in Australia …” but nothing was said about how I was going to escape from my family. I had been eighteen that June so I was still not my own mistress.

I did enjoy our talks, though. I loved hearing about his home out there and I felt I knew the ostentatious house already . for I was sure it was ostentatious with a name like Peacocks. I could never picture it without peacocks on the lawn and the human Peacock strutting with them. There was a housekeeper, a Mrs. Laud, to whom Ben referred now and then and who seemed to be a most efficient woman for whom he felt some affection. She had a son and daughter - Jimson working with the Company and Lilias who helped her mother in the house; there were also a number of servants, and among them were several what he called “Abos’, the term for aborigines.

I would listen avidly and again and again I asked: “Yes, Ben, but how am I going to get there? Then he would give his sly laugh.

“You leave that to me,” he would say.

I saw Hannah now and then and was still on good terms with the servants at the Hall, for I always found time to visit them.

“Mr. Henniker’s told me he’ll be leaving soon,” said Mrs’ Bucket.

“He’s told Mr. Wilmot too. So then we’ll arrange to shut up again and it’ll be as it was before he came back without his leg. I don’t think it’s right for a house like this. The servants don’t like it. That’s what comes of people who don’t belong. You’ll miss them, I reckon.”

I almost blurted out that he had plans, but I realized then how wild those plans were, and it occurred to me then that he talked of them to placate me and that he knew as well as I did that I should never be able to leave.

There was a knock on the door of my room and Miriam came in. She looked quite pretty.

“I want to talk to you, Jessica,” she said.

“What do you think? Ernest and I are going to get married.”

I put my arms round her and kissed her because I was so pleased that she had at last come to her senses. I didn’t remember when I had last done that, but I knew it pleased her because she went pink to the tips of her ears and nose.

“I’m very happy,” she went on.

“We decided that no matter what Mama said we would wait no longer.”

“I’m so glad, Miriam,” I cried.

“You should have done it years ago.

Never mind. You have at last. So when shall you be married? “

“Ernest says there is no sense in waiting. We have waited long enough.

We were waiting, you know, for him to get St. Clissold’s because the vicar there is very, very old, but he just goes on living and could live for another ten years. “

“No use waiting for dead men’s shoes or dead vicars’ vestments. I think it’s wonderful, and I’m glad you’ve come to your senses. It’s lovely and I hope you’ll be very happy.”

“We shall be very poor. Papa can give me nothing, and I still have to tell Mama.”

“Don’t let her stop you.”

“Nothing could stop me now. Ifs rather a blessing that we have been so poor lately-though not as poor as Ernest and I shall be. It means that I have learned how to make everything go a long way…”

“I’m sure you’re right, Miriam. When is the wedding to be?”

Miriam looked really frightened.

“At the end of August. Ernest says we’d better put up the banns right away and then no one can stop us.

There’s the little curate’s cottage in the vicarage grounds where Ernest lives alone. But there’ll be room for two of us. “

“You’ll manage very well, Miriam.”

I was glad she had made the decision and the change in her was miraculous. My grandmother was naturally angry and sceptical. She referred slightingly to ‘our lovesick girl’ and how some people seemed to think they could live like church mice on the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table. I bubbled over with mirth at that and pointed out that she did not know her Bible as it certainly was not the mice who had devoured those very special crumbs.

“You have become impossible, Jessica,” she told me.

“I don’t know what this household is coming to. How different things might have been if some people had taken their responsibilities more seriously. Perhaps then we shouldn’t have foolish old maids making laughing-stocks of themselves in the mad rush to marry anybody-just anybody before it is too late.”

Miriam was wounded and wavered, but only slightly. She was Ernest’s future wife now, not merely my grandmother’s daughter, and she quoted him whenever possible. I was delighted. I talked to her often and we grew more friendly than we ever had been. I told her she was doing the right thing in escaping from my grandmother’s tyranny, that she was fortunate to be able to and that she was going to be very happy.

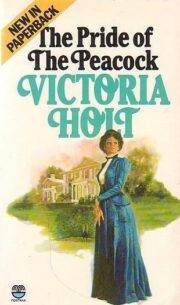

"The Pride of the Peacock" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Pride of the Peacock". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Pride of the Peacock" друзьям в соцсетях.